Methotrexate: the great and the terrible

No, no, today we will not talk about the Great and Terrible Goodwin from the Emerald City) Methotrexate... Whatever is attributed to this drug, as soon as it is not called (dangerous chemotherapy, terrible poison and poison, and these are only the most modest epithets). The fear of methotrexate is sometimes even greater than the fear of rheumatic disease itself. Patients secretly hate him and dream of “getting off” him as quickly as possible, drawing in their imagination terrible pictures of irreparable harm to the body. Meanwhile, methotrexate is one of the main drugs used in rheumatology. So who is he: friend or enemy? To be afraid or to accept without fear? We'll figure it out today...

Among modern medications used to treat rheumatoid arthritis and other rheumatic diseases, methotrexate occupies a special place. Back in the early 80s of the last century, several clinical trials were conducted on the effectiveness of the drug at a dose of 7.5–15 mg/week, and later – up to 25 mg/week in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The clinical efficacy of the drug and its dose dependence were assessed. Until the early 90s, methotrexate was considered as a reserve drug, treatment with which was started when other basic anti-inflammatory drugs (DMARDs) were ineffective. Currently, methotrexate has received the status of the “gold standard” among DMARDs used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, I think you have heard this phrase more than once. According to preliminary estimates, more than half a million (!) patients use methotrexate for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis alone. The unique place of methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis is determined by many circumstances.

First, the effectiveness of methotrexate has been confirmed in a large number of open-label, controlled studies and observational studies. It has been shown that when treating with methotrexate, the effectiveness lasts longer and the toxicity is less pronounced than when using other basic drugs. In Russia, methotrexate has been used for the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, including its early variants, since 1984, the maximum duration of continuous therapy is 28 years (on average 14.8 years) (according to the Research Institute of Rheumatology). According to Australian rheumatologists, 75.4% of patients have been using methotrexate for more than 6 years and 53% for more than 12 years. Preliminary results indicate the pharmacoeconomic advantages of methotrexate over other basic anti-inflammatory drugs. In addition, there are studies that confirm lower mortality with long-term therapy with methotrexate compared to other basic drugs.

The unique place of methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis is determined by the fact that it is currently one of the most effective standard DMARDs and can be prescribed at any stage of arthritis. It is characterized by the highest duration of continuous use and simple dosing. Methorexate therapy is characterized by well-known and controlled (!!!) toxic reactions, as well as a relatively low cost of treatment.

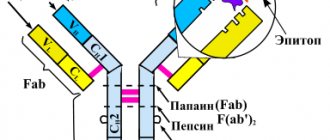

Mechanism of action

The mechanism of action of methotrexate is based on its antifolate properties. The anti-inflammatory activity of relatively low doses of the drug (10–20 mg/week), in contrast to ultra-high doses (100–1000 mg/m2), is realized due to the activity of its derivatives, which can induce the formation of a powerful anti-inflammatory mediator - adenosine. The adenosine-dependent effects of methotrexate include a decrease in the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-6, -8, -10, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), etc. These effects allow methotrexate prescribed for the treatment of rheumatic diseases to be considered not as immunosuppressive (suppressive immunity), but more as an anti-inflammatory drug, which is confirmed by clinical practice. Methotrexate has obvious immunomodulatory activity, inhibiting the synthesis of pro-inflammatory substances and stimulating the synthesis of anti-inflammatory substances.

Pharmacological properties

When taken orally, methotrexate, undergoing some changes, enters the liver through the portal vein. After taking methotrexate at a dose of 10–25 mg, drug absorption ranges from 25 to 100% (average 60–70%). The maximum concentration of the drug in the blood is achieved after 2–4 hours. Although taking methotrexate with food slows the achievement of peak concentrations, its absorption and bioavailability are not affected, so the drug can be taken with food. Methotrexate binds to albumin and is excreted primarily by the kidneys (80%) and to a lesser extent by the liver (10–30%). The development of renal failure leads to a slowdown in the release of the drug and increases its toxicity. Methotrexate metabolites (that is, substances formed during the transformation process in the body) are found inside cells for ≥7 days after a single dose, which determines the frequency of taking the drug once a week.

Side effects

Side effects that develop during treatment with methotrexate can be divided into three main groups:

1) effects associated with folate deficiency (stomatitis, inhibition of hematopoiesis) can usually be corrected by administering folic or folinic acids and/or discontinuing methotrexate (temporary or permanent). The use of methotrexate without the prescription of folic acid is unacceptable!!!

2) allergic reactions, which sometimes disappear when treatment is interrupted. Harbingers of such reactions can be considered the appearance of an unmotivated dry cough with a rapid change in ambient temperature, for example, when going outside, or, conversely, shortness of breath;

3) reactions associated with the accumulation of active metabolites of the drug (liver damage). According to a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials (RCTs), the incidence of adverse reactions during treatment with methotrexate is approximately 22%, and in patients receiving placebo it is 7%.

Gastrointestinal tract

Nausea and vomiting usually appear 1–8 days after taking methotrexate and last 1–3 days, but can occur at any time during treatment. In this case, it is necessary to temporarily discontinue the drug and switch to subcutaneous administration of the drug. For mild nausea on the day of taking the drug and/or the next day, Motilium can be used situationally. Methotrexate may slow the scarring of gastric and duodenal ulcers, especially during concomitant use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Ulcerative lesions of the mucous membrane of the upper gastrointestinal tract are a relative contraindication for the use of methotrexate. On the other hand, methotrexate is the most common and accessible drug for the treatment of arthritis, so the detection of ulcerative lesions of the mucous membrane only indicates the need for targeted and thorough antiulcer treatment, and not the exclusion of methotrexate from therapy. Patients are often successfully treated with methotrexate for many years without recurrence of acute gastric ulcers, especially since with the effectiveness of methotrexate, NSAIDs can be discontinued and the source of stress ulcers, such as pain, decreases or disappears.

Liver

The most common side effect during therapy is a temporary increase in the level of aminotransferases (ALAT, AST) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP). As a rule, the concentration of aminotransferases reaches a maximum 4–5 days after taking the drug and persists for 1–2 weeks. A two-fold increase in aminotransferase levels is NOT a reason to discontinue methotrexate, whereas a more significant increase indicates the need to reduce the dose or interrupt treatment. With a multiple increase, in addition to the abolition of methotrexate, hepatoprotectors are usually prescribed. After normalization of aminotransferase levels, therapy is resumed at a lower dose, and subsequently the dose can be increased or left unchanged. Data regarding the likelihood of developing liver cirrhosis during treatment are contradictory. There are reports that liver damage during treatment with methotrexate is more common in patients with psoriasis. Liver changes during morphological examination are detected in only 3–11% of patients receiving methotrexate for more than 2 years, but liver cirrhosis develops very rarely (approximately 1 in 1000 patients). Regular monitoring of aminotransferase levels is considered sufficient as an early and reliable marker of liver damage. In this regard, the complete abstinence of patients from alcohol is of fundamental importance!!! People with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are more likely to have more severe liver damage and a higher rate of progression of liver damage than people with rheumatoid arthritis. Risk factors for liver damage during treatment include:

- alcohol consumption,

- lack of folic acid intake,

- total dose of methotrexate and duration of therapy,

- presence of diabetes mellitus,

- obesity,

- elderly age.

In patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate, aminotransferase levels should be monitored at least once every 3 months!

Methotrexate and viral hepatitis

A serious problem is the prescription of methotrexate in the presence of carriage of hepatitis B and/or C viruses. Determination of markers of hepatitis B and C is included in the standards for examining patients before prescribing methotrexate. However, when HBsAg or anti-HCV is detected, further studies to determine viremia and its severity are usually not carried out. Apparently, incomplete examination, as well as the lack of long-term observations, are often the reasons for a calm attitude towards prescribing methotrexate to such patients.

Hematopoietic system

Changes in blood parameters during methotrexate therapy are observed relatively rarely (no more than 1–3% of cases). Cases of leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, megaloblastic anemia, and pancytopenia have been described. Pancytopenia (that is, a decrease in all blood counts) is a deadly complication of therapy. The severity of this condition correlates with the dose of the drug, the presence of renal failure, concomitant infection, folic acid deficiency, and the combination of methotrexate with other toxic drugs. Unfortunately, taking folic acid does not prevent the development of pancytopenia. Elderly patients are at greatest risk of developing severe cytopenia. Normalization of hematopoiesis after discontinuation of the drug in most patients occurs within 2 weeks, but in some cases it becomes necessary to prescribe high doses of folate and even a colony-stimulating factor. In addition to cytopenia, that is, a decrease in blood counts, methotrexate in some cases can cause leukocytosis (that is, an increase in the level of white blood cells) without developing an infection.

Infectious complications during methotrexate therapy develop relatively often. These may be recurrent respiratory diseases, purulent bronchitis, and less often - unusually severe fungal and viral infections - nocardiosis, pulmonary aspergillosis and toxoplasmosis, herpes, cryptococcosis, Pneumocystis pneumonia. The development of severe infections is grounds for urgent withdrawal of methotrexate. But fortunately, according to several studies, long-term use of methotrexate is NOT associated with an increased risk of infectious complications.

Teratogenicity

Methotrexate is embryotoxic and has a teratogenic effect. Low doses of methotrexate can lead to the development of defects in the fetus, for example, the so-called “methotrexate syndrome”. Developmental delays and mental impairment have been described in children born to mothers who took the drug during pregnancy. Since even a single dose of methotrexate can cause defects in the fetus, this drug is contraindicated for pregnant women or women planning pregnancy! Methotrexate remains in the cells for a long time, so a washout period of at least 3–6 months is recommended before conception.

The cardiovascular system

An important advantage of methotrexate, which distinguishes it from other basic drugs, is the reduction in the risk of cardiovascular complications, which are the main cause of premature death in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. According to the literature and numerous studies in recent years, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis during treatment with methotrexate, there is a decrease in mortality from cardiovascular complications (up to 70%!!!) compared to patients receiving other DMARDs. It is believed that the beneficial effect of methotrexate on the cardiovascular system may be associated with increased formation of adenosine. However, many patients develop hypercholesterolemia (increased cholesterol levels in the blood), which requires the prescription of statins. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis often experience increased homocysteine concentrations and impaired homocysteine metabolism, regardless of treatment. Hyperhomocysteinemia is considered a risk factor for thrombosis. This indicates the need for long-term studies assessing all possible factors determining the development and progression of cardiovascular system pathology in patients.

Flu-like syndrome or post-dose reactions

Cases have been described of the appearance 24 hours after taking methotrexate of pain in the joints and muscles, general malaise, sometimes accompanied by fever and lasting from 1 to 4 days. These reactions indicate the need to discontinue treatment and are considered the second most common cause after gastrointestinal symptoms. Some patients experience headache, memory loss, and photophobia. Unfortunately, many patients complain of headaches of varying severity and memory loss. This is another area that requires study and identification of approaches to reduce the incidence of adverse reactions. The currently very limited number of available and effective DMARDs makes it impossible to discontinue methotrexate in many patients with headache and/or complaints of some memory loss. At the same time, the development of a post-dose reaction in all cases requires discontinuation of the drug.

Methotrexate nodulosis

In patients receiving methotrexate, the development of subcutaneous nodules has been described, differing from rheumatoid nodules in smaller size and atypical localization, this is called methotrexate nodulosis (nodulation). Typically, these atypical nodules are localized on the hands. Methotrexate nodulosis can develop in patients who are seronegative for rheumatoid factor (RF) and during the period of remission of arthritis. There is evidence that the administration of hydroxychloroquine in most cases leads to regression of nodulosis.

Methotrexate for psoriatic arthritis

Methotrexate has been used to treat psoriatic arthritis since 1964. Compared with other basic drugs, methotrexate is well tolerated in this disease, and the frequency of treatment interruptions is lower than with other drugs. However, 10–30% of patients experience side effects that require discontinuation of the drug. Liver damage develops 3 times more often than when treating patients with rheumatoid arthritis with methotrexate. Methotrexate has long been used to treat severe forms of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Currently, the dose of methotrexate is usually 20–30 mg/week, with a maintenance dose of 10–15 mg/week. Typically, the indications for prescribing methotrexate for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are as follows:

- malignant form of psoriatic arthritis;

- rapidly progressing course of the disease;

- high laboratory activity;

- development of severe skin variants of psoriasis (exudative, pustular, erythrodermic);

- low effectiveness or poor tolerability of NSAIDs and glucocorticoids;

- ineffectiveness of other DMARDs.

Still's disease in adults

Positive results were obtained from the use of methotrexate at a dose of up to 20 mg/week: improvement and development of remission of the disease, a significant reduction in the dose of hormonal drugs, positive dynamics of laboratory parameters.

Dermatomyositis/polymyositis

The effectiveness of methotrexate in the treatment of these diseases does not depend on the route of administration (oral or intravenous) and is 50–75%. Methotrexate is often used in combination with glucocorticoids. Therapy begins with a small dose (7.5–10 mg/week), which is increased to 25–30 mg/week. If oral methotrexate is poorly tolerated, an intravenous route of administration is prescribed. Other methods (subcutaneous, intramuscular) are unacceptable in these cases. The dose of the drug is reduced gradually under careful monitoring of clinical manifestations and CPK levels.

Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis

In elderly patients suffering from these diseases, in the treatment of which glucocorticoids are used, the administration of methotrexate in doses of 10–12.5 mg/week has been considered in a number of studies as an opportunity to more quickly reduce the dose of hormones and maintain remission.

Subcutaneous use of methotrexate

In clinical practice, methotrexate is most often used orally, but recently there has been a trend toward more widespread subcutaneous administration of the drug, especially at doses ≥20 mg/week. The theoretical rationale for subcutaneous methotrexate is the wide variability in its oral availability (20–80%), whereas the availability of subcutaneous methotrexate is much higher and more consistent. According to a number of authors, switching patients from parenteral to oral methotrexate led to an increase in the clinical activity of the disease in 49–71% of cases and the development of undesirable side effects (nausea, increased aminotransferase levels). When parenteral administration of methotrexate was resumed, the majority of patients experienced normalization of such disorders. RK Moitra et al. analyzed the results of parenteral use of methotrexate in 102 patients who had previously taken it orally for 3–135 months, and noted an increase in clinical effect and a decrease in ESR in approximately half of the patients. In 2010, methotrexate appeared in Russia in prefilled syringes for subcutaneous administration (Metoject), which opened up new opportunities for optimizing the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

In conclusion, I would like to highlight the following points:

- From the standpoint of evidence-based medicine, methotrexate is a DMARD that can be used in various types and durations of rheumatoid arthritis, in patients with undifferentiated arthritis, in early rheumatoid arthritis to achieve (induce) remission, in various rheumatic diseases.

- The sufficiently high effectiveness of the drug, the possibility of dose adjustment and the low frequency of intolerance reactions allow therapy to be carried out continuously for many years.

- The dose of methotrexate should be individualized, and therapy should be aimed at suppressing the activity and progression of the disease. Treatment should begin with a dose of 10-15 mg/week and increase by 5 mg every 2-4 weeks up to 25-30 mg/week depending on effectiveness and tolerability.

- Before prescribing methotrexate, risk factors for severe adverse reactions, including alcohol consumption, should be assessed.

- Treatment with methotrexate should be interrupted at least 3-6 months before the planned pregnancy.

- And, perhaps, the most important thing: the success and safety of methotrexate therapy, as with the use of other drugs, depend on the partnership between the doctor and the patient. If you have any doubts or questions, you can always contact your doctor, I won’t get tired of repeating this!!! If you believe in the success of treatment, you will definitely achieve it!

Variability in methotrexate-associated hepatotoxicity

Materials and methods

A population-based cohort study was conducted in patients with psoriasis, psariatic arthritis (PsA), and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who received methotrexate between 1997 and 2015;

The researchers compared the rates of mild liver disease, moderate and severe liver disease, cirrhosis, and cirrhosis-related hospitalizations between the groups.

A total of 5687 patients with psoriasis, 6520 patients with PsA and 28,030 patients with RA met the inclusion criteria of having one or more prescriptions for methotrexate or receiving methotrexate in a clinic during the study period.

results

- Patients with RA tended to be older (mean 59.7 years) and the group consisted of more women (71.6%) than patients with psoriasis (47.7 years; 45.3% women) or patients with PsA (50.7 years; 57.3% women).

- Between 17.9% and 23.5% of participants had a history of smoking, and between 2.8% and 7.4% had a history of alcohol abuse; the incidence of diabetes was 7.0% to 8.3%, and that of hyperlipidemia or statin use was 13.6% to 16.4%.

- The mean weekly dose of methotrexate was similar in the three groups of patients (mean 19.2–19.9 mg).

- However, the duration of methotrexate use in patients with RA was longer (mean 72.1 weeks) compared to the groups of patients with PsA (56.3 weeks) and psoriasis (43.0 weeks).

- Additionally, 50% of patients in the RA group discontinued treatment at 80 months, 50% of patients in the PsA group discontinued treatment at 54 months, and 50% of patients with psoriasis discontinued treatment at 26 months.

- Patients with RA also had a higher cumulative dose of methotrexate (mean 4.0 g) compared with the PsA (3.0 g) and psoriasis (2.1) groups.

- When researchers looked at incidence rates (IR) for different categories of liver disease, they found the following differences:

- Mild liver disease: The IR per 1000 person-years for patients with psoriasis was 4.22 per 1000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 3.61–4.91) compared with 2.39 per 1000 person-years (95 % CI, 1.95–2.91) for patients with PsA and 1.39 per 1000 person-years (95% CI 1.25–1.55) for patients with RA.

- Moderate to severe liver disease: The IR for patients with psoriasis was 0.98 per 1000 person-years (95% CI, 0.70–1.33), compared with 0.51 (95% CI, 0.32–1.33). 0.77) for patients with PsA and 0.46 (95% CI 0.37-0.55) for patients with RA.

- Cirrhosis: The IR for patients with psoriasis was 1.89 per 1000 person-years (95% CI, 1.49–2.37), compared with 0.84 (95% CI, 0.59–1.16) for patients with PsA and 0.42 (95% CI, 0.34–0.37). 0.51) for patients with RA.

- Hospitalization for cirrhosis: This was the least common outcome IR 0.73 per 1000 person-years (95% CI, 0.49–1.05) for patients with psoriasis, 0.32 (95% CI, 0.18– 0.54) for patients with PsA, and 0.22 (95% CI, 0.17–0.29) for patients with RA.

- When the results were adjusted by Cox regression analysis, the psoriasis group had a significantly increased risk compared with the RA group for mild liver disease (hazard ratio, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.81-2.72), moderate and severe liver disease (RR 1.56; 95% CI 1.05–2.31), cirrhosis (RR 3.38; 95% CI 2.44–4.68) and cirrhosis-related hospitalization (RR 2.25 ; 95% CI 1.37–3.69).

- Compared with patients with RA, patients with PsA had a significantly increased risk of mild liver disease (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.01-1.60) and cirrhosis (HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.10-2.42).

Conclusion

Patients taking methotrexate for psoriasis or PsA had a higher risk of developing liver disease than RA patients taking methotrexate. The researchers noted that it is unclear why there is a difference in risk between the three groups of patients. While such differences in the risk of hepatotoxicity have previously been attributed to differences in rates of alcoholism, obesity, diabetes, and other comorbidities, the current study shows that underlying disease affects the risk of liver disease regardless of age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption, presence of diabetes, hyperlipidemia, concomitant pathology and weekly dose of methotrexate. In addition, the results do not indicate whether the liver disease is due to methotrexate use, the underlying disease, or a combination of these factors.

Source:

medscape.com/viewarticle/946521#vp_1

Positive experience of using the drug methotrexate in a teenager with psoriatic arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory joint disease that develops in approximately one third of patients with psoriasis [1–3]. Arthritis associated with psoriasis was first described in France in 1818.

PsA in adults belongs to the group of seronegative spondyloarthritis. According to the 1998 Durban classification, PsA in children is classified as juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Every year, PsA affects 4–8 children out of 100,000. Its frequency in the structure of juvenile arthritis is 4–9%, about 3 million children. Juvenile PsA is 2 times more common in girls. There are two peaks of incidence: early age (3–5 years) and adolescence (14–16 years).

The etiology of PsA is still unclear. It is assumed that genetic, immunological and environmental factors are most significant in the occurrence and course of psoriasis and PsA

In most patients with PsA, there is no chronological relationship between skin and joint damage, although arthritis is more common in patients with severe psoriasis. In approximately 75% of patients, skin lesions precede the development of arthritis, in 10–15% they occur simultaneously, but in 10–15% of cases, arthritis develops before psoriasis.

In children, in 50% of cases, arthritis precedes the onset of psoriasis. However, even if a child has skin manifestations, it is not as clearly expressed as in adults, so it is often examined by doctors.

PsA can begin gradually, gradually (first symptoms: increased fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia, enthesopathy, weight loss). Approximately a third of children at the onset of the disease experience paroxysmal, sharp pain, swelling and stiffness in the joints, expressed in the morning hours

In the vast majority of patients (80%), PsA is more often manifested by arthritis of the distal, proximal interphalangeal joints of the fingers, knee joints, and, less commonly, metacarpophalangeal and metatarsophalangeal joints, as well as shoulder joints [1–3].

The most common division of PsA into five clinical forms:

1) asymmetric oligoarthritis; 2) arthritis of the distal interphalangeal joints; 3) symmetrical rheumatoid-like arthritis; 4) arthritis mutilans; 5) psoriatic spondylitis.

The classification of PsA is very arbitrary; its forms are unstable and can transform into one another over time.

In 70% of cases, PsA manifests itself as asymmetric mono-, oligoarthritis (asymmetry is a characteristic feature of this disease). This pathology is also characterized by the involvement in the onset of the disease of the so-called exception joints (interphalangeal joint of the first finger and proximal interphalangeal joint of the fifth finger). A special feature of PsA is that all joints of one finger are affected - axial, or axial, arthritis. Tenosynovitis of the flexor tendons is often observed, which gives the affected finger a sausage-shaped appearance. The skin over the affected joints, especially the fingers and toes, often becomes purple or purple-bluish in color. Interestingly, the pain of such a joint, including palpation, is usually mild [1–4].

Arthritis of the distal interphalangeal joints is the most typical manifestation of PsA, which is why it is distinguished as a separate form. But such an isolated process is extremely rare. Much more often it is combined with lesions of other joints and nails. In 5% of patients with PsA, symmetrical rheumatoid-like lesions of the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the fingers are observed. Sometimes this form of the disease at its onset creates significant difficulties in differential diagnosis with the polyarticular variant of juvenile idiopathic arthritis [1–4].

Mutilating (disfiguring) arthritis is a unique form of PsA and is manifested by severe destructive arthritis of the distal extremities, mainly the fingers and toes. As a result of osteolysis, the fingers are shortened and their characteristic deformation (“telescopic finger”) or hand deformity (“lorgnette hand”) develops. Pathological mobility of the phalanges occurs, leading to significant impairment of limb function [1–4].

In 40% of patients with PsA, spinal involvement is observed (psoriatic spondylitis), more often combined with arthritis of peripheral joints. In 5% of patients, isolated damage to the axial skeleton is observed. Changes in the spine in PsA may be no different from the changes characteristic of ankylosing spondylitis: the beginning is pain in the lumbar region of an inflammatory nature, then successive damage to the thoracic, cervical regions, costovertebral joints, the formation of a characteristic “supplicant pose”. These patients are often carriers of the histocompatibility antigen HLA-B27 [1–4].

Diagnosis of PsA is nonspecific: there are no special laboratory tests, they only reflect the presence and severity of the inflammatory process [1, 3]. The X-ray picture of PsA is characterized by a number of features: asymmetry of X-ray symptoms, rare development of periarticular osteoporosis, and the presence of bone proliferation.

To make a diagnosis, the Vancouver diagnostic criteria for PsA (1989) are used: 1) arthritis and a typical psoriatic rash or 2) arthritis and the presence of at least three “minor” signs:

a) changes in nails (thimble syndrome, onycholysis); b) psoriasis in 1st or 2nd degree relatives; c) psoriasis-like rash; d) dactylitis.

Probable PsA: arthritis + at least two of the minor signs.

Treatment of PsA is complex and carried out jointly with dermatologists. Therapy includes symptom-modifying drugs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids); disease-modifying drugs (derived anti-inflammatory drugs (DMARDs) - methotrexate, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine, leflunomide, etc.); therapy with biological agents and local therapy is used.

Currently, methotrexate is the No. 1 basic antirheumatic drug worldwide for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis and, accordingly, PsA. It affects two main manifestations of this disease - joint and skin syndromes. A significant number of scientific studies on the use of methotrexate have been conducted in different countries of the world, which has made it possible to create a serious evidence base for the effectiveness of this drug [5, 6].

In pediatric rheumatology practice, methotrexate is used at a dose of 10–15 mg/m2 in tablet or parenteral forms. According to the results of numerous studies, it has been shown that in order to achieve maximum effect, subcutaneous or intramuscular administration of the drug is advisable [7–9], which ensures a faster onset of action of the drug, reproducible bioavailability, and reduced side effects from the gastrointestinal tract. The drug methotrexate is registered in the Russian Federation, which is produced in pre-filled syringes with various dosages, ready for administration, even by children, independently subcutaneously. It should be noted that ready-to-use syringes with methotrexate are safe, easy to use, do not require special storage conditions, and make it easier for patients and their parents to carry out daily procedures [10]. A new form of the drug methotrexate is now available - a solution for subcutaneous administration. The main difference of the new form: a 5-fold reduction in the volume of the administered drug due to an increase in the concentration of the active substance, which makes the injection less painful for the child [10].

Clinical case

Patient V., born in 1999, is being observed at the University Children's Clinical Hospital of the First Moscow State Medical University named after. I.M. Sechenov since November 2011 with the diagnosis: “Psoriatic arthritis, arthritis of the distal interphalangeal joints. Psoriatic nail lesions. Seronegative, grade 1 activity, radiographic stage I, functional class 2A.”

From the early medical history it is known that the girl from her third pregnancy, which proceeded with the threat of termination in the first trimester, had her first urgent, independent birth. Birth weight 3350 g, body length 51 cm, she screamed immediately. From birth on artificial feeding. Complementary foods from 4 months. Among the diseases suffered: in the first year of life, anemia, dystrophy, then frequent acute respiratory viral infections, acute bronchitis. Mantoux reactions before 2010 were negative. The family history is burdened with arterial hypertension and chronic gastritis. Allergy history without any special features.

From the medical history: the girl has been sick since October 2009, when changes in the nail plates first appeared in the form of thickening. In March 2010, changes in the periungual area appeared in the form of peeling with bleeding defects. The child was consulted at MONIKI, psoriasis was suspected and Elok was prescribed locally - without effect. In July 2010, after hyperinsolation (vacation in Egypt), articular syndrome developed in the form of swelling of the distal phalanges of the first fingers of both hands and the fourth finger of the right hand. In October 2010, she was consulted at the Scientific Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences; according to ultrasound data, periarthritis of the distal phalanges of the fourth finger of the right hand and the first finger of the hands was revealed; onychodystrophy. Presumable diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis. During examination: ESR 16 mm/hour, HLA B40+, HLA B27-. From December 2010 to January 2011, she was hospitalized at the Scientific Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences. Humoral activity remained (ESR 20 mm/hour), there was no immunological activity. According to ultrasound of the hands - tenosynovitis of the extensor muscles of the first finger of the left hand; X-rays of the hands and feet - single cyst-like clearings, valgus deformity of the first metacarpophalangeal joints of the hands. According to MRI, cysts and no erosions were detected. A diagnosis of psoriatic arthropathy, psoriatic nail lesions was made. Sulfasalazine 750 mg/day was prescribed as basic therapy. The patient received the drug for 6 months, and then the drug was discontinued on her own due to abdominal pain. Since November 2011, the child has been observed at the UDKB PMGMU named after. I.M. Sechenov with a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis, arthritis of the distal interphalangeal joints with psoriatic lesions of the nails.

Upon admission: valgus deformity of the first metacarpophalangeal joint (Fig. 1). Exudative-proliferative changes are more proliferative in nature in the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints with deforming arthritis of the first fingers of both hands and the fourth finger of the right hand with severe limitation of mobility in the joints and moderate pain during movement. In other joints, movements are full and painless. Otto's test +5.0 cm, Schober's test +5.0 cm, Thomayer's test 0 cm. There are no enthesopathies. Active joints - 4. Joints with limited mobility - 4. Onychodystrophy of the 1st and 3rd fingers of the left hand and the 1st and 4th fingers of the right hand. Psoriatic changes at the base of the nail plate of the first finger of the right hand.

During the examination: high humoral and immunological activity was noted (ESR 28–19 mm/h, IgG 2340–1840 mg/dL (N 600–2000 mg/dL)), positive antinuclear factor (ANF), and therefore to exclude uveitis the girl was consulted by an ophthalmologist at the Research Institute named after. Helmholtz. Uveitis is excluded. Subsequently, the ANF is negative.

Due to the presence of humoral and immunological activity, as well as the activity of articular and skin syndromes, the girl was prescribed basic therapy with methotrexate 15 mg/week intramuscularly at the rate of 11.2 mg/m2 once a week together with folic acid daily, except during the day administration of methotrexate. The therapy was well tolerated. During methotrexate therapy, the girl showed stabilization of the underlying disease - there were no signs of articular syndrome activity (ESR 5-7-8 mm/h), no immunological activity, rare skin rashes were noted on the extensor surfaces of the forearm, in the area of the elbow joints.

At the moment, the articular syndrome (Fig. 2) is represented by proliferative changes in the interphalangeal joints of the 1st and 4th fingers of the right hand and the 1st and 3rd fingers of the left hand; valgus deformity of the first metacarpophalangeal joints of both hands, Otto test +5.0 cm, Schober test +5.0 cm. Thomaier test 0 cm. No enthesopathies. Active joints - 0. Joints with limited mobility - 4.

Considering the stable remission of the articular syndrome for three years, it is recommended to reduce the dose of the basic drug methotrexate to 12.5 mg/week (from October 5, 2015) under the control of general and biochemical blood tests.

Conclusion

Thus, the use of the drug methotrexate in patient V. with psoriatic arthritis had a pronounced therapeutic effect, which was manifested by the achievement of stable clinical and laboratory remission of the articular syndrome and a decrease in the manifestations of skin psoriasis, improvement of functional activity and an increase in the patient’s quality of life.

Literature

- Bunchuk N.V., Badokin V.V., Korotaeva T.V. Psoriatic arthritis. In the book: Rheumatology national guide. Ed. Nasonova E. L., Nasonova V. A. M.: GEOTARMEDIA, 2008. P. 355–366.

- Chebysheva S. N. Psoriatic arthritis. Guide to pediatric rheumatology / Edited by N. A. Geppe, N. S. Podchernyaeva, G. A. Lyskina. M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2011. pp. 285–299.

- Chebysheva S. N., Zholobova E. S., Geppe N. A., Meleshkina A. V. Diagnosis, clinic and therapy of psoriatic arthritis in children // Doctor Ru. 2012; 9 (77); With. 28–33.

- Veale D., Ritchlin S., FitzGerald O. Immunopathology of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis // Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005, 64 (Suppl. II), p. 26–29.

- Cassidy JT Outcomes research in the therapeutic use of methotrexate in children with chronic peripheral arthritis // J Pediatr. 1998; 133: r. 179–180.

- Tambic-Bukovac L., Malcic I., Prohic A. Personal experience with methotrexate in the treatment of idiopathic juvenile arthritis // Rheumatism. 2002; 49 (1): p. 20–24.

- Tukova J., Chladek J., Nemcova D. et al. Methotrexate bioavailability after oral and subcutaneous administration in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis // ClinExpRheumatol. 2009; 27 (6): p. 1047–1053.

- Alsufyani K., Ortiz-Alvarez O., Cabral DA et al. The role of subcutaneous administration of methotrexate in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis who have failed oral methotrexate // J Rheumatol. 2004; 31 (1): p. 179–182.

- Klein A., Kaul I., Foeldvari I., Ganser G., Urban A., Horneff G. Efficacy and safety of oral and parental methotrexate therapy in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: an observational study with patients from the German Methotrexate Registry / /ArthritisCareRes (Hoboken). 2012; 64 (9): p. 1349–1356.

- Korotaeva T.V., Batkaev E.A., Chamurlieva M.N., Loginova E.Yu. Psoriatic arthritis. Tutorial. M., 2021. P. 43.

S. N. Chebysheva1, Candidate of Medical Sciences E. S. Zholobova, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor N. A. Geppe, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor A. V. Meleshkina, Candidate of Medical Sciences M. N. Nikolaeva K. V. Aleksanyan

FSBEI HE First Moscow State Medical University named after. I. M. Sechenova Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow

1 Contact information

About the difficulties of vaccinating people with autoimmune diseases against COVID-19.

Scientific director of the Research Institute of Rheumatology named after. V.A. Nasonova, chief freelance specialist - rheumatologist of Russia, Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences Evgeniy Nasonov and head of the laboratory for studying comorbid infections and monitoring the safety of drug therapy Boris Belov in an interview with MV spoke about the difficulties of vaccinating people with autoimmune diseases against COVID-19.

– What are the features of the immune response to COVID-19?

‒ Evgeniy Nasonov (E.N.):

There is now more and more evidence that in severe cases of COVID-19, autoantibodies are detected in half of patients, and disorders in the immune system are very reminiscent of the picture of autoimmune rheumatic diseases, for example, systemic lupus erythematosus.

The immune response is of enormous importance in the development of severe complications of coronavirus infection. A normal immune system response leads to rapid recovery, which occurs in the vast majority of people despite risk factors for severe COVID-19.

Some patients develop a “hyperimmune response.” I would call this a “perfect cytokine storm” - the accumulation of a large number of not very significant circumstances that lead to serious consequences. This is characteristic of a cytokine storm in COVID-19, unlike that seen in cancer therapy, transplantation, or sepsis.

It turns out: the stronger the immune response to coronavirus, the more unfavorable the prognosis. This phenomenon is characteristic of autoimmune diseases, when high levels of autoantibodies correlate with severe organ pathology.

– What factors should a physician consider when deciding whether to vaccinate a patient with an autoimmune disease against COVID-19?

‒ Boris Belov (B.B.):

There are no generally accepted recommendations yet. We advocate vaccination, but we do not fully understand all the problems associated with the safety and effectiveness of vaccines. There are points that need to be taken into account: the disease itself, its activity, the therapy being carried out. The influence of all these factors on the post-vaccination response is unknown and requires study.

In the near future we will begin clinical studies, possibly with the involvement of other scientific and clinical centers. We will present final recommendations after completion of the clinical trial at our institute.

– For which rheumatic diseases (or course variants) is vaccination against COVID-19 contraindicated?

‒ B.B.:

There are no such diseases. The main thing is to know when, at what stage of the disease and therapy the vaccine should be used.

At the end of 2021, the European League Against Rheumatism issued recommendations for vaccination of patients with autoimmune rheumatic inflammatory diseases. First of all, they relate to vaccines against influenza and pneumococcal infection, which are actively recommended for all patients during the COVID-19 period. The only absolute contraindication may be intolerance to any components of the drug.

Provided that the presence of rheumatic disease and the therapy provided (with some reservations) do not play a significant role, the presence of rheumatic disease is well controlled. On the other hand, uncontrolled disease activity is one of the most important risk factors for comorbid infections. It is essential to maintain patient protection while maintaining active therapy for rheumatic disease.

‒ E.N.:

I want to emphasize one important point. Infectious complications, including opportunistic infections, are a specific side effect of even innovative “targeted” anti-inflammatory drugs. But the risk of infection is not as high as with commonly prescribed immunosuppressive drugs.

Millions of patients around the world and in our country receive targeted therapy for a long time, for example, TNF-alpha inhibitors or interleukin-6 inhibitors. It is possible to treat for a long time with new anti-inflammatory drugs without increasing the risk of infectious complications to a critical level, as was the case with long-term therapy with cyclophosphamide or some other drugs.

We believe that the problem of infections is so important for rheumatology that all remedies are good. The best of them is vaccination.

– The doctor should take into account the technology used in the vaccine: vector, peptide, inactivated?

‒ B.B.:

One circumstance is fundamentally important for our patients - the vaccine must be inactivated. We are placing our main bet on CoviVac, which presents the antigenic set of the virus itself, and not just the S-protein.

After all, it is not entirely clear how the immunity of a healthy person and a patient receiving immunosuppressive therapy will react to certain sets of antigens.

Let me emphasize that we are also interested in studying the Sputnik V drug in a cohort of patients with rheumatological diseases. The scientific interest is very great, not to mention the practical significance.

– Can vaccination give impetus to the debut of an autoimmune disease?

‒ E.N.:

Without a doubt. The risk-benefit ratio is very important. In this case, the benefits of vaccination outweigh the risks.

Ideally, it would be good to have biomarkers to assess and minimize risk.

– Are additional studies required in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases after vaccine administration?

‒ E.N.:

It is interesting to look at the level of neutralizing antibodies of various isotypes, the cellular immune response and, of course, autoantibodies.

We need to understand how much the autoimmune background influences the mechanisms of immunization, because this is a model of infection, only modified in a special way. Most likely, patients will be protected, but the question is whether this will lead to any consequences.

At the same time, the most important practical component should not be overlooked behind scientific problems: if patients do get sick, they tolerate the infection more easily. Therefore, we are supporters of vaccination and are obliged to give only informed recommendations.

– Is additional screening required for patients with a family history (first- or second-degree relatives with autoimmune pathology) before vaccination?

‒ B.B.:

There is a term “hereditary predisposition to autoimmune diseases.” This does not mean that this predisposition is realized during life. But under certain factors, the development of autoimmune pathology is possible.

We are interested in following first-degree relatives of patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases and their response to COVID-19 vaccination. We planned this as the next stage of our research.

– Let’s formulate what a doctor should know about the patient, what research should be done to recommend vaccination?

‒ E.N.:

The simplest question is: “Have you had any history of problems with vaccination?” If there were, this in itself is a limitation. It is necessary to understand what is at stake.

You should pay attention to the activity of the inflammatory process. If a patient has an ESR of 40‒50 or 100 mm/h or a C-reactive protein greater than 20 mg/L, indicating signs of infection or uncontrolled disease activity, vaccination should not be recommended in this situation. It's dangerous, and we don't even know how dangerous it is.

It is necessary to take into account what kind of disease the patient has. In a simplified form, rheumatic diseases can be divided into two categories: immunoinflammatory - these are rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, where inflammation plays a central role, and rarer autoimmune diseases - systemic lupus erythematosus, for example.

The therapy the patient is receiving should be taken into account. For example, rituximab occupies a central place in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. This is the only drug that can suppress B-cell activity and, without a doubt, reduce the antiviral immune response. This does not mean that patients get sick more often or suffer more severely from viral infections, which, by the way, is paradoxical. There are other mechanisms of antiviral defense, not just antibodies. However, antibody titers are lower in those receiving rituximab, so there are strict recommendations: six months between vaccine administrations.

In this regard, Janus kinase inhibitors seem convenient.

These are tablet drugs with a very short action. Intuitively (although this still needs to be proven), this method of therapy seems convenient. The drug stops working approximately one and a half to two days after discontinuation. This allows for better harmonization of therapy with vaccination. This is still a hypothesis, but, in my opinion, it has a right to exist. Source: https://medvestnik.ru/content/articles/Immunnyi-otvet-na-slojnyi-vopros.html

METHOTREXATE EBEVE solution for injection. 10 mg/ml vial. 5 ml

Directions for use and doses

Methotrexate is included in many chemotherapy treatment regimens, and therefore, when choosing the route of administration, regimen and doses in each individual case, one should be guided by data from specialized literature.

The drug Megotrexate-Ebewe in the dosage form of an injection solution can be administered intramuscularly, subcutaneously, intravenously, intraarterially or intrathecally. Doses of the drug over 100 mg/m2 are administered only intravenously! The solution is pre-diluted with 5% dextrose solution. When using high doses of the drug (above 100 mg/m2), subsequent administration of calcium folinate is mandatory.

Methotrexate for the treatment of rheumatic diseases or skin diseases should only be used once a week! Improper use of methotrexate can lead to serious adverse effects, including death. The following dosage regimens are used:

Trophoblastic tumors:

15-30 mg intramuscularly, daily for 5 days at intervals of one or more weeks (depending on signs of toxicity). Or 50 mg once every 5 days with an interval of at least 1 month. Courses of treatment are usually repeated 3 to 5 times up to a total dose of 300-400 mg.

Solid tumors:

in combination with other antitumor drugs

drugs 30-40 mg/m2 intravenously once a week. Leukemia and lymphoma:

200-500 mg/m2 by intravenous infusion once every 2-4 weeks.

Neuroleukemia:

12 mg/m2 intrathecally over 15-30 seconds 1 or 2 times a week.

When treating children, the dose is selected depending on the age of the child: children under 1 year of age are prescribed 6 mg, children under 1 year of age - 8 mg, children under 2 years of age - 10 mg, children aged 3 years and older - 12 mg. Before administration, a volume of cerebrospinal fluid approximately equal to the volume of the drug to be administered should be removed. For intrathecal administration, methotrexate is diluted to a concentration of 1 mg/ml in 0.9% isotonic sodium chloride solution. It should be administered intrathecally with caution. Exceeding the recommended dose for intrathecal administration significantly increases the risk of severe toxicity.

Caution: Do not administer calcium folinate intrathecally!

Mycosis fungoides:

intramuscularly 50 mg once a week or 25 mg 2 times a week per day for several weeks or months. Dose reduction or discontinuation of the drug is determined by the patient's response and hematological parameters.

Dermatomyositis:

adults 7.5-15 mg per week, children 2.5-7.5 mg per week. Subsequently, the dose is reduced until the lowest effective dose is reached and used for a long time, for months, in combination with a maintenance dose of glucocorticosteroids.

Systemic lupus erythematosus:

adults 15 mg per week, children 7.5-10 mg/m2. The course of treatment is 6-8 weeks, then a maintenance dose is used for many months.

Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis:

a week before the start of treatment, it is recommended to administer a test dose of 5-10 mg of methotrexate parenterally to identify an intolerance reaction.

The recommended starting dose is 7.5 mg methotrexate once a week intramuscularly, intravenously or subcutaneously. The dose should be gradually increased, with the maximum dose not exceeding 30 mg of methotrexate per week. Response to treatment usually occurs 2-6 weeks after starting the drug. When the optimal clinical effect is achieved, dose reduction begins until the lowest effective dose is achieved.

Rheumatoid arthritis:

The initial dose is usually 7.5 mg once a week, which is administered simultaneously intravenously, intramuscularly or subcutaneously. To achieve optimal effect, the weekly dose can be gradually increased (2.5 mg per week), but it should not exceed 20 mg. When optimal clinical effect is achieved (usually 4-8 weeks after initiation of therapy), dose reduction should begin to achieve the lowest effective maintenance dose.

The optimal duration of therapy has not been established; in each specific case, the duration of therapy is determined by the doctor. Juvenile chronic arthritis:

in children under 16 years of age at a dose of 10-20 mg/m2 once a week. Typically, an effective dose is 10-15 mg/m2 per week. Initially, the drug is used in half the dose. If well tolerated, use the full dose after a week. In children and adolescents, if parenteral administration of the drug is necessary, due to the fact that the available data on the safety of intravenous administration are limited, the subcutaneous or intramuscular route of administration should be used. Due to limited data on the effectiveness and safety of methotrexate in children under 3 years of age, it is not recommended to use the drug in this group of patients. When using methotrexate in children as immunosuppressive therapy (psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile chronic arthritis, dermatomyositis and systemic lupus erythematosus), the benefit/risk ratio of use should be carefully considered.

Method of use of the syringe (pre-filled): Subcutaneous.

The injection needle included in the package is intended only for subcutaneous administration of Methotrexate-Ebeve.

The pre-filled syringe is equipped with a special automatic needle protection system.

Select a site to administer the drug. For subcutaneous application, choose a location where you can reach a 2-3 cm fold of skin, usually in the abdomen or thighs, as shown in the picture. If someone helps you, it is possible to give an injection in the forearm. If the intended injection site is the abdominal area, then it is necessary to retreat at least 3 fingers' width from the navel. It is recommended to alternate sides (left, right) of injections, as well as choose different locations on the thighs or abdomen.

Do not inject the drug subcutaneously near scars, bruises, red or swollen areas, or close to the groin. To minimize bruising, it is recommended to avoid injecting into skin where a network of small blood vessels is visible on the surface. Remove the inner package containing the prefilled syringe and needle. Open the inner package by pulling the cut corner. Remove the syringe.

Remove the gray rubber cap from the syringe without touching the opened inside of the syringe. Place the syringe back into the inner packaging without worrying about the yellow solution running out. Make sure that the integrity of the security label is not damaged. Remove the cap, attach the needle without removing the protective cover from it, and secure the needle to the syringe. Before using the syringe, the intended injection site should be pre-disinfected.

Pull the cap (strictly at a right angle) to remove it. Do not touch the protective cover of the needle.

Using two fingers, form a fold of skin and quickly insert the needle completely into the skin (at an angle of about 90 degrees) until the protective mechanism is completely retracted. Slowly inject the contents of the syringe under the skin. Gently pull out the needle, after which it will automatically retract into the syringe.

If you notice blood at the injection site after removing the needle, apply a cotton swab to the injection site until the blood or medication is absorbed. Minor bleeding or leakage of the drug will soon stop. If necessary, apply a bandage. Do not rub the injection site.

If the skin at the injection site turns yellow, do not worry, within one or two days the drug will be absorbed and the skin color will return to normal. This may occur due to improper subcutaneous injection or insufficient needle length. Patients with impaired renal function require dose adjustment depending on creatinine clearance (with a creatinine clearance of 30-50 ml/min, the dose is reduced by 50%; with a creatinine clearance of less than 30 ml/min, the use of methotrexate is contraindicated).

In patients with impaired liver function, Methotrexate-Ebeve is used with caution. Methotrexate should not be used if the plasma bilirubin concentration is more than 5 mg/dL (85.5 µmol/L). Elderly patients (over 65 years of age) may need to reduce the dose of methotrexate because liver and kidney function deteriorates with age, as well as a decrease in folate levels in the body.