Cytostatics, from the Greek “making the cell immobile,” have been used in oncology since 1947. These drugs disrupt the life of the cell, forcing it to commit suicide - apoptosis. Cytostatics are used not only to treat malignant processes, but also rheumatic and autoimmune diseases.

- What are cytostatics?

- Classification of cytostatics

- How do cytostatics work?

- Scope of application of cytostatics

- Indications and contraindications for the use of cytostatics

- Side effects of cytostatics

- Mechanism of action of cytostatics

- What cytostatics are most often prescribed?

What are cytostatics?

Chemotherapy is exclusively the use of cytostatics. In addition to chemotherapy, antitumor treatment includes endocrine effects using hormonal drugs, targeted therapy that “turns off” a certain biochemical reaction, and the use of biological - immuno-oncological agents, which themselves do not act on the malignant cell, but activate immune defenders.

Cytostatics damage all rapidly dividing cells - any malignant and normal cells in the blood, bone marrow and gonads. Over time, cell clones develop resistance to cytostatics, reducing the effectiveness of chemotherapy.

Classification of cytostatics

All cytostatic drugs are divided into 4 large groups according to their mechanism of action or origin:

- alkylating cytostatics , which entangle DNA strands by forming unscheduled bonds with them;

- antimetabolites are very similar in appearance to human protein substances involved in cellular activity, but unlike natural ones, their interference leads to cell death;

- antitumor antibiotics are of the same chemical origin as the antibacterial drugs that we use to fight inflammation and infections, but they do not affect the bacterial flora, but they kill cancer cells;

- cytostatics of plant origin have similar mechanisms of damage to cellular structures, but the main unifying principle is their initial production from plant materials; now most are synthesized in the laboratory.

Hormones have nothing to do with cytostatics, since their effect is to antagonize natural sex hormones or to directly or indirectly block their production. A lack of hormones or their replacement with an antihormone also leads to cell death.

Modern strategy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis

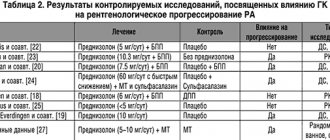

The prevalence and severity of this pathology, the complexity of the pathogenetic mechanisms, the heterogeneity of the clinical forms and course of the disease make its therapy a serious challenge. RA negatively affects not only patients and their families, but also society as a whole due to disability, decreased patient productivity, and the need for resource-intensive medical care, which emphasizes the importance of effective patient management [3,4]. Over the past two decades, optimization of the use of synthetic disease-modifying anti-inflammatory drugs (DMARDs) and the emergence of genetically engineered biological drugs (GEBPs) have made it possible to effectively suppress inflammation, inhibit joint destruction and improve treatment outcomes in general. Treatment goals have changed from controlling inflammatory symptoms and achieving low levels of disease activity to achieving and maintaining clinical remission in a significant number of patients. In addition to suppressing inflammation, inhibiting the progression of joint destruction has also become an important and achievable goal [5]. Finally, with the help of modern methods of drug therapy, it is possible to preserve and restore functional capabilities, reduce the likelihood of developing concomitant RA pathology (atherosclerosis), restore the quality of life of patients, and also maintain their social activity. Assessment of RA outcomes, based on an analysis of long-term dynamics of disease activity and progression in long-term cohort studies and clinical observations, allows us to draw the following main conclusions regarding the possibilities of disease control [6–14]: • RA is a heterogeneous disease in terms of clinical and immunological characteristics, inflammatory activity and rate of progression of destructive changes; • the main factors determining the outcomes of RA are the severity and persistence of inflammation; • at an early stage of the disease, treatment is most effective; • early prescribed pathogenetic therapy makes it possible to control the activity of RA to one degree or another, including the possibility of developing persistently low disease activity and clinical remission; • different methods of pathogenetic therapy may have different potential for inhibiting structural disorders. One of the most important advances in the treatment of RA has been the introduction of biological therapy. In the Russian Federation, 8 drugs of this group are currently registered for the treatment of RA (Table 1). If treatment with DMARDs, primarily methotrexate, is the basis of drug therapy for RA [1,2,13,14], then GEBD is the main means of overcoming drug resistance in patients with a severe, torpid course of the disease. The introduction of modern methods of aggressive therapy for RA has changed the idea of the goal of treatment - as stated above, this is the achievement of clinical remission in the majority of patients [15,16]. Despite the importance of introducing new drugs, optimal treatment strategy is now recognized as a major component of achieving therapeutic success. The main principles of successful treatment of RA based on data from a large meta-analysis [17] are: • immediate initiation of active therapy after diagnosis; • active management of the patient, careful monitoring of his condition; • selection of a new treatment regimen if the previous one is insufficiently effective. These principles are based on a fairly large evidence base. At the same time, the authors of the meta-analysis specifically note that there is no reason to believe that any specific drug regimen has significant advantages over others. The paradigm of intensive treatment in the early stage of RA For patients with early RA, it has been clearly shown that active therapy with DMARDs, primarily methotrexate, started immediately after diagnosis, is effective not only in terms of suppressing symptoms (pain and stiffness), inflammatory activity, and reducing the severity of functional disorders , but also in relation to the prevention of disability (see below), including slowing the progression of destructive changes in the joints. Treatment with synthetic DMARDs (methotrexate, leflunomide or sulfasalazine) is not only clinically effective [18–21] but can also suppress radiographic progression [20,22]. BIBPs have also been reliably shown to be highly effective in reducing the clinical symptoms of RA and slowing down radiological progression [23]. The paradigm of early intensive treatment consists of prescribing aggressive therapy for RA as quickly as possible immediately after verification of the diagnosis. The Finnish study of synthetic DMARD combination therapy compared with DMARD monotherapy (FIN-RACO) in the early RA group [24] showed that within 2 years, 71% of patients in the DMARD combination therapy group achieved a 50% clinical response (ACR50) compared from 58% when using monotherapy. Interestingly, after 5 years, both groups had similar rates of improvement in clinical activity parameters, but the combination therapy group showed significantly less radiographic progression [25]. A meta-analysis comparing early (less than 2 years of disease) initiation of DMARDs versus delayed initiation of synthetic DMARDs demonstrated a significant reduction in long-term rates of radiographic progression in RA patients treated with DMARDs early in the disease [26]. Targeted Therapy and Tight Control in RA Until now, many of the decisions made by physicians to initiate and modify RA therapy have relied on subjective assessments of disease activity and functional impairment by physician and patient. At the same time, clinical instruments for quantitative assessment of disease activity and the patient’s functional state have now been developed and tested, as well as recommended by medical communities and officially adopted in many countries [1,2]. In RA over the last decade, the paradigm of “strict control” of the patient’s condition, borrowed from other areas of medicine, such as diabetology, has been actively used. Several large studies (TICORA, BeST, CAMERA, the already mentioned FIN-RACO) have provided important data showing that it is possible to improve clinical outcomes in patients with RA without prescribing innovative drugs, but only using active patient management with the definition of specific treatment goals and using quantitative methods to assess disease activity [24,27–29]. In the TICORA trial [28], in the “tight control” or intensive therapy group, treatment with standard DMARDs was intensified if disease activity at the time of the rheumatology visit was greater than specific target activity indices. In the conventional therapy group, when examined every 3 months. changes in therapy were based on physician judgment rather than on assessment of disease activity or were made with a specific goal in mind. As a result, the intensive therapy group was characterized by lower disease activity and a high rate of clinical remission of the disease compared to the conventional therapy group. In the CAMERA trial for early RA [29], patients in the intensive therapy group had their methotrexate dose adjusted monthly based on response to therapy by quantifying disease activity using a computer decision-making program. The result also showed a significant improvement in clinical response compared with the usual management group. In summary, clinical studies have confirmed that targeted therapy for RA using quantitative assessments of disease activity leads to significant improvements in clinical outcomes. Strategy "Treat to target" - "Treatment to achieve the goal" The modern paradigm for the management of patients with RA was presented in 2010 in the international program "Treat to target" (T2T) - "Treatment to achieve the goal" [30,31]. The T2T program does not specify specific treatment methods, but outlines general principles and recommendations for optimal patient management. The consensus reached is based on data obtained from a systematic review of the literature that describes strategic therapeutic approaches that provide the best results. The latest regulations were adopted in March 2009, and 60 experts from 25 countries in Europe, North and Latin America, Japan and Australia, as well as patient representatives, took part in their development. The guidelines do not mention any specific drugs or classes of drugs; The primary focus here is on therapeutic strategies aimed at improving the care of patients with RA. The general principles of T2T are formulated as follows: A. Treatment of RA should be carried out based on the joint decision of the patient and the rheumatologist. B. The primary goal in treating a patient with RA is to maintain a high health-related quality of life for as long as possible by controlling symptoms, preventing structural joint damage, normalizing function, and increasing the patient's social opportunities. C. Suppressing inflammation is the most important way to achieve this goal. D. Treating to target by assessing disease activity and tailoring therapy accordingly helps optimize outcomes in RA. Based on general principles, the international committee has developed 10 T2T recommendations for the treatment of RA to achieve the goal, based on scientific evidence and expert opinion. 1. The primary goal of RA treatment is to achieve a state of clinical remission. 2. Clinical remission is defined as the absence of signs of significant inflammatory activity. 3. Although the primary goal remains to achieve remission, based on the available scientific evidence, achieving low RA activity may be considered an acceptable alternative treatment goal, especially in stable and long-term disease. 4. Until the treatment goal is achieved, drug therapy must be reviewed at least once every 3 months. 5. It is necessary to regularly assess and document data on disease activity: in patients with moderate/high degrees of activity - monthly, in patients with persistently low activity or in remission - less often (once every 3-6 months). 6. In everyday clinical practice, validated comprehensive indicators of disease activity, including assessment of joint condition, should be used to make treatment decisions. 7. In addition to the use of comprehensive measures of disease activity, clinical decision making must consider structural changes and dysfunction. 8. The desired treatment goal must be achieved throughout the entire period of the disease. 9. The choice of (composite) disease activity measure and target parameters may be influenced by comorbidities, individual patient characteristics, and drug risks. 10. The patient should be sufficiently informed about the goal of treatment and the planned strategy to achieve this goal under the supervision of a rheumatologist. The algorithm for managing a patient with RA in accordance with the T2T strategy can be presented in graphical form (Fig. 1). The following principles of the T2T initiative are especially important for Russian rheumatological practice [31]: 1. Focus on maintaining quality of life and social activity (as opposed to the often practice of quickly determining disability). 2. Careful control over the treatment process using modern integral indicators of disease activity and, accordingly, increasing the role of a rheumatologist in the medical care system. 3. Active suppression of the inflammatory process in order to achieve remission, which became possible thanks to the introduction of biologically active drugs. 4. Maintaining the achieved improvement with the help of targeted therapy during the period of illness (in fact, throughout the patient’s entire life), which dictates the need to improve drug supply. Recommendations regarding specific drugs and treatment regimens are based on data from large meta-analyses. With regard to traditional (synthetic) DMARDs, such as methotrexate, leflunomide, etc., which are still the basis of pathogenetic therapy for RA, the following conclusions are substantiated [32]: • methotrexate among all synthetic DMARDs is the most effective in relation to RA activity and structural damage; • leflunomide is close to methotrexate in effectiveness; • sulfasalazine and gold salts (injectable) are effective against symptoms and structural damage; • cyclosporine, hydroxychloroquine, minocycline, tacrolimus are effective against joint syndrome; • auranofin and D-penicillamine do not have strictly proven superiority over placebo; • cyclophosphamide and azathioprine increase the risk of tumors and infections. Thus, a systematic analysis confirmed that methotrexate deservedly occupies the position of the “gold standard” of pathogenetic therapy for RA and should be prescribed (in the absence of contraindications) as a first-line drug among DMARDs. Glucocorticoids (GCs) remain an important component of RA treatment. The following basic facts are known regarding their use in RA [33]: • GCs are effective as bridge therapy (that is, with relatively short-term administration in low and medium doses for the period before the onset of DMARD action or when changing basic drugs); • in early RA, low doses of GCs (≤7.5 mg/day in terms of prednisolone) can reduce radiological progression; • for advanced and late RA, GC doses are ≤15 mg/day. help reduce disease activity; • The dose of GC can be slowly reduced once success is achieved. Currently, the most dynamically developing group of anti-rheumatic drugs, biologically active drugs, is represented in Russia by 8 drugs that have different mechanisms of action and are directed against different target molecules (Table 1). The most long-term and widely used drugs in rheumatology among the biologically active drugs are tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) inhibitors, which include the monoclonal antibodies infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab, a recombinant molecule containing a soluble TNF-α receptor - etanercept, and a drug containing a PEGylated Fab fragment of the anti-TNF-α antibody certolizumab pegol. TNF-α inhibitors are traditionally considered to be the first-line drugs of biological therapy, since they (more precisely, infliximab and etanercept) were the world’s first representatives of biologically active drugs and have the largest evidence base for RA. At the same time, data accumulated in recent years indicate the possibility of using other biological therapy drugs, such as rituximab or tocilizumab, as first-line drugs for biological therapy. According to one of the large systematic analyzes [34], the most evidence-based data are the following regarding the use of GEBD in RA: • effective when initially prescribed in patients who have not previously received methotrexate: infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, abatacept; • effective in patients with insufficient effectiveness of methotrexate: infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, rituximab, tocilizumab, abatacept; • in case of insufficient response to TNF inhibitors, switching to rituximab, tocilizumab, abatacept is effective; • switching to another anti-TNF if the effect of the first drug from this group is insufficient is possible, but less supported by facts; • TNF inhibitors increase the likelihood of infections. As part of the activities of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), new clinical guidelines for the treatment of RA were created in 2010 [35]. They, just like the T2T program, contain basic principles and actual recommendations. The basic principles are formulated as follows: • rheumatologists are specialists who primarily deal with patients with RA; • treatment of patients with RA should be aimed at the best results and be based on a joint decision between the doctor and the patient; • RA is an expensive disease in terms of medical and productivity costs, which should be considered by the treating rheumatologist. The EULAR recommendations for the treatment of RA are summarized below: 1. As soon as a patient is diagnosed with RA, he should immediately be treated with a synthetic DMARD. 2. The goal of treatment is to achieve remission or low disease activity in each patient as quickly as possible. If this goal is not achieved, it is necessary to select therapy through frequent monitoring (every 1–3 months). 3. Methotrexate should be part of the first strategic treatment regimen in patients with active RA. 4. In the case of contraindications for the appointment of methotrexate (or its intolerance), the following BPVP should be discussed as a (first) treatment strategy: sulfasalazine, leflunomide and gold salt (injections). 5. For patients who have not previously received BPVP, monotherapy is recommended, and not combined therapy with synthetic BPVP. 6. Civil Code can be useful as the initial method of therapy (short -term) in combination with synthetic BPVP. 7. If, after the initial purpose of the BPVP, the purpose of therapy is not achieved, then in the presence of factors of adverse prognosis (positive tests for the rheumatoid factor and anticrollin antibodies, early appearance of erosion, rapid progression, high activity of the disease) should be discussed the addition of fibers, and in the absence of factors of adverse forecast - switching to another synthetic BPVP. 8. Patches and/or other synthetic BPVPs should not be prescribed to patients who do not respond enough to methotrexate. The current practice is the appointment of the FNO -α inhibitor, which should be combined with methotrexate. 9. In case of failure (ineffectiveness or intolerance) of therapy, the first inhibitor of the FNO patient should be prescribed a second TNF inhibitor, abatactic, rituximab or toxilizumab. 10. In case of refractory severe RA or in the presence of contraindications to the gibeen or previously indicated synthetic BPVP, the purpose of the following drugs in monotherapy or combinations with the above drugs may be discussed: Azatioprine, Cyclosporine A, Cyclophosphamide. 11. Intensive treatment strategies should be used in each patient, primarily in patients with adverse prognostic factors. 12. If the patient has a persistent remission, then the dose of the Civil Code should be reduced, it is possible to discuss a reduction in the dose of the gibeen, especially if this therapy is combined with synthetic BPVP. 13. In the case of a long stable remission, a careful dose of BPVP as a general decision of the doctor and the patient can be discussed. 14. In patients who have factors of unfavorable forecast and previously not received BPVP, the purpose of methotrexate in combination with the gibeen (as the first treatment regimen) may be discussed. 15. In the selection of therapy, in addition to the activity of the disease, factors such as the progression of radiological changes, concomitant diseases and consideration of treatment safety should be taken into account. In the clinical recommendations of the EULAR for the treatment of RA, an emphasis is made on the maximum beginning of therapy with potent drugs, such as methotrexat and gibeen. At the same time, for patients with a serious forecast, it is possible to use the combination of methotrexate and gibPs as the first scheme of pathogenetic therapy. For practice, a concretization of the T2T algorithm is needed. Given the Eular recommendations, a scheme may be presented (Fig. 2). Treatment should begin with methotrexate, optimal use of its form for subcutaneous injection, which can be more effective and well -tolerated compared to oral forms. If necessary, the patient should be transferred to a combination of methotrexate and gibeen. In case of success, the last treatment regimen is preserved, in the absence of achieving the goal, therapy is again reviewed on a quarterly. The medical and social consequences of the introduction of a modern treatment strategy in countries where rheumatological assistance to the population is sufficiently developed, to date, convincing data on significant positive shifts have been obtained in terms of reducing the burden of the disease for society. One of the most important consequences of the introduction of a modern aggressive treatment strategy for RA was a decrease in persistent disability of patients. So, according to the Swedish National Social Register (Swedish National Social Insurance Register) [36], in the 1990s. RA was the cause of almost 2% of all cases of persistent disability that required the payment of pension. This percentage significantly (up to 1.5%) decreased by 2000, and by 2009 it reduced twice (1%). In Finland [37] there was a decrease in disability of patients with RA with disability in the first 2 years from the onset of the disease from 8.9% in 2000 to 4.8% in 2007 in the USA from the United States [38] it was noted that a risk reduction in Disability was observed already when comparing groups of patients with RA, taken under observation at the beginning and in the late 1990s. At the same time, despite the good results in clinical practice in some cohorts of patients with RA, for example, using an adalimumab [39,40], other cohort studies [41], as well as meta -analyzes [42] show that the purpose of the gibe It does not give such a pronounced effect regarding disability of patients. Thus, it was the new treatment strategy for RA that caused a significant reduction in persistent disability. Another important consequence of a change in the treatment strategy for the need to reduce the need for large orthopedo -surgical operations, such as joint endoprosthetics [43]. A striking example is messages from the Scandinavian countries. So, according to Swedish registers [44], for the period from 1998 to 2006, the frequency of total thigh endoprosthetics in patients with RA also reduced almost double (from 12.6 to 6.6 per 1000 patients). In fairness, it should be noted that such a pattern was not revealed in relation to the total arthroplasty of the knee joint. Similar messages about a decrease in the need for orthopedic surgery for RA are published by researchers of various countries with different levels of financing of medical care, such as the United States [45], Japan [46] and Brazil [47]. It is noteworthy that this trend has already been outlined by the beginning of the 2000s, in the “anticipation” of RA therapy (this indicates the independent meaning of the concept of early aggressive therapy using methotrexate and other active BPVP), and continued to develop with a wide The introduction of the Gibpp. Conclusion with an increase in the number of drugs for the treatment of RA doctors and patients are faced with the need to make difficult decisions regarding the initiation and cessation of various types of drug therapy. Numerous studies confirm the importance of choosing the correct strategy of the patient, which is currently most concentrated in the recommendations of T2T. It is necessary to include this strategy in the routine clinical practice in order to optimize the results of treatment and reduce the damage that RA inflows to society.

Literature 1. Clinical recommendations. Rheumatology. / Ed. E.L. Nasonova. M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2010. 2. Rheumatology: national guide. / Ed. E.L. Nasonova M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2008. 720 p. 3. Nasonov E.L. Rheumatoid arthritis as a general medical problem // Ter. archive. 2004. No. 5. P. 5–7. 4. Mease PJ Improving the routine management of rheumatoid arthritis: the value of tight control // J. Rheumatol. 2010. Vol. 3. R. 1570–1578. 5. Agarwal SK Core Management Principles in Rheumatoid Arthritis to Help Guide Managed Care Professionals // Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 2011. Vol. 17. R. 3–9. 6. Nasonov E.L. Why is early diagnosis and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis necessary? // RMJ. 2002. T. 10. No. 22. P. 1009–1010. 7. Emery P. Therapeutic approaches for early rheumatoid arthritis. How early? How aggressive? // Br. J. Rheumatol. 1995. Vol. 34. R. 87–90. 8. Karateev D.E., Ivanova M.M., Balabanova R.M., Akimova T.F. Analysis of lethal outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis during long-term observation // Russian Rheumatology 1998. No. 1. P. 17–28. 9. Emery P., Breedveld FC, Dougados M. et al. Early referral recommendation for newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis: evidence based development of a clinical guide // Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2002. Vol. 61. R. 290–297. 10. Nasonov E.L. Pharmacotherapy of rheumatoid arthritis from the perspective of evidence-based medicine: new recommendations // RMJ. 2002. T. 10. No. 6. pp. 294–302. 11. Karateev D.E. Retrospective assessment of long-term basic therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis // Scientific and practical rheumatology. 2003. No. 3. pp. 32–36. 12. Karateev D.E. Main trends and variability in the evolution of rheumatoid arthritis: results of long-term observation // Scientific and practical rheumatology. 2004. No. 1. P. 8–14. 13. Nasonov E.L., Karateev D.E., Chichasova N.V., Chemeris N.A. Modern standards of pharmacotherapy for rheumatoid arthritis // Klin. Pharmacol. therapy. 2005. No. 1. P. 72–75. 14. Karateev D.E., Luchikhina E.L., Togizbaev G. Modern principles of management of patients with early arthritis // RMJ. 2008. T. 16. No. 24. pp. 1610–1615. 15. Smolen JS, Aletaha D., Machold KP Therapeutic strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract. Res//Clin. Rheumatol. 2005. Vol. 19. R. 163–177. 16. Karateev D.E. Low activity and remission in rheumatoid arthritis: clinical, immunological and morphological aspects // Scientific and practical rheumatology. 2009. No. 5. P. 4–12. 17. Knevel R., Schoels M., Huizinga T. et al. Current evidence of a strategic approach to the management of rheumatoid arthritis with the disease modifying anti–rheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis // Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010. Vol. 69. R. 987–994. 18. Weinblatt ME, Coblyn JS, Fox DA et al. Efficacy of low-dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis // N Engl J Med. 1985. Vol. 312. R. 818–822. 19. Williams HJ, Willkens RF, Samuelson CO Jr. et al. Comparison of low–dose oral pulse methotrexate and placebo in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. A controlled clinical trial // Arthritis Rheum. 1985. Vol. 28. R. 721–730. 20. Cohen S., Cannon G. W., Schiff M. et al. Two-year, blinded, random-ized, controlled trial of treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis with leflunomide compared with methotrexate. Utilization of leflunomide in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis Trial Investigator Group // Arthritis Rheum. 2001. Vol. 44. R. 1984–1992. 21. Smolen JS, Kalden JR, Scott DL et al. Efficacy and safety of leflunomide compared with placebo and sulphasalazine in active rheumatoid arthritis: a double–blind, randomized, multicentre trial. European Leflunomide Study Group // Lancet. 1999. Vol. 353 (9149).R. 259–266. 22. Sharp JT, Strand V., Leung H., Hurley F., Loew–Friedrich I. Treatment with leflunomide slows radiographic progression of rheumatoid arthritis: results from three randomized controlled trials of leflunomide in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Leflunomide Rheumatoid Arthritis Investigators Group // Arthritis Rheum. 2000. Vol. 43. R. 495–505. 23. Furst DE, Keystone EC, Braun J. et al. Updated consensus statement on biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, 2011 // Ann Rheum Dis. 2012. Vol. 71. Suppl 2. R. 2–45. 24. Mottonen T., Hannonen P., Leirisalo-Repo M. et al. Comparison of combination therapy with single-drug therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. FIN–RACo trial group // Lancet. 1999. Vol. 353 (9164). R. 1568–1573. 25. Korpela M., Laasonen L., Hannonen P. et al. Retardation of joint damage in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis by initial aggressive treatment with disease–modifying antirheumatic drugs: five–year experience from the FIN–RACo study // Arthritis Rheum. 2004. Vol. 50. R. 2072–2081. 26. Finckh A., Liang MH, van Herckenrode CM, de Pablo P. Long-term impact of early treatment on radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis // Arthritis Rheum. 2006. Vol. 55. R. 864–872. 27. Goekoop–Ruiterman YP, de Vries–Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial // Arthritis Rheum. 2005. Vol. 52. R. 3381–3390. 28. Grigor C., Capell H., Stirling A. et al. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single–blind random–dominated controlled trial // Lancet. 2004. Vol. 364 (9430). R. 263–269. 29. Verstappen SM, Jacobs JW, van der Veen MJ et al. Utrecht Rheumatoid Arthritis Cohort study group. Intensive treatment with methotrexate in early rheumatoid arthritis: aiming for remission. Computer Assisted Management in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (CAMERA, an open–label strategy trial) // Ann Rheum Dis. 2007. Vol. 66. R. 1443–1149. 30. Smolen J., Aletaha D., Bijlsma J. et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force // Ann Rheum Dis. 2010. Vol. 69. R. 631–637. 31. Karateev D.E. Academy of Rheumatology on Russian soil // Consilium medicum. 2010, extra edition. pp. 3–14. 32. Gaujoux-Viala C., Smolen J., Landewe R. et al. Current evidence for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic disease modifying anti–rheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review in forming the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis // Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010. Vol. 69. R. 1004–1009. 33. Gorter S., Bijlsma J., Cutolo M. et al. Current evidence for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with glucocorticoids: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis // Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010. Vol. 69. R. 1010–1014. 34. Nam J., Winthrop K., Cutolo M. et al. Current evidence for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with biological disease modifying anti–rheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of RA // Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010. Vol. 69. R. 976–986. 35. Smolen J., Landewe R., Breedveld F. et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease–modifying antirheumatic drugs // Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010. Vol. 69. R. 964–975. 36. Hallert E., Husberg M., Bernfort L. The incidence of permanent work disability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Sweden 1990–2010: before and after introduction of biological agents // Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012. Vol. 51. R. 338–346. 37. Rantalaiho V.M., Kautiainen H., Jarvenpaa S. et al. Decline in work disability caused by early rheumatoid arthritis: results from a nationwide Finnish register, 2000–8 // Ann Rheum Dis. 2012, Jun 7. . 38. Nikiphorou E., Guh D., Bansback N. et al. Work disability rates in RA. Results from an inception cohort with 24 years follow-up. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012. Vol. 51. R. 385–392. 39. Kruger K., Wollenhaupt J., Lorenz HM et al. Reduction in sickness absence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving adalimumab: data from a German non-interventional study // Rheumatol Int. 2011, Dec 30. , doi: 10.1007/s00296–011–2033–5. Epub 2011 Aug 6. 40. Kleinert S., Tony HP, Krause A. et al. Impact of patient and disease characteristics on therapeutic success during adalimumab treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: data from a German noninterventional observational study // Rheumatol Int. 20, Vol. 32. R. 2759–2767. 41. Allaire S., Wolfe F., Niu J. et al. Evaluation of the effect of anti-tumor necrosis factor agent use on rheumatoid arthritis work disability: the jury is still out // Arthritis Rheum. 2008, Aug 15. Vol. 59 (8). R. 1082–1089. 42. Wee MM, Lems WF, Usan H. et al. The effect of biological agents on work participation in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a systematic review // Ann Rheum Dis. 2012. Vol. 71. R. 161–171. 43. Khan N., Sokka T. Declining needs for total joint replacements for rheumatoid arthritis // Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2011. Vol. 13. R. 130–131. 44. Hekmat K., Jacobsson L., Nilsson J–A., et al. Decrease in the incidence of total hip arthroplasties in patients with rheumatoid arthritis – results from a well defined population in south Sweden // Arthritis Res Ther. 2011. Vol. 13. R67. 45. Da Silva E, Doran MF, Crowson CS et al. Declining use of orthopedic surgery in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? Results of a long-term, population-based assessment // Arthritis Rheum. 2003. Vol. 49. R. 216–220. 46. Momohara S., Inoue E., Ikari K. et l. Decrease in orthopedic operations, including total joint replacements, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis between 2001 and 2007: data from Japanese outpatients in a single institute–based large observational cohort (IORRA) // Ann Rheum Dis. 2010. Vol. 69. R. 312–313. 47. De Piano LP, Golmia RP, Scheinberg MA Decreased need for large joint replacement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a specialized Brazilian center // Clin Rheumatol. 2011. Vol. 30. R. 549–550.

How do cytostatics work?

Ultimately, all methods of cytostatic effects lead to the same thing - cell apoptosis. Apoptosis is a natural stage of cellular life, in contrast to death due to inflammation, infection, and necrosis. This is programmed death, each cell comes to it in its own time, and cytostatics lead to it outside the program. Every day in the human body, 100 billion cells undergo apoptosis; we can assume that every two years the cellular composition of the body is completely renewed. In a simplified form, apoptosis is represented as follows:

- formation of a biochemical signal to trigger death, a kind of cellular awareness of the need to die;

- production of intracellular enzymes that burn cellular “insides”;

- absorption of the dead body by neighboring cells and macrophages;

- decomposition by intracellular lysosomes of what is eaten into microelements for further use.

The process proceeds according to the principle “there was and there is no”, which is why during chemotherapy there is no inflammation or scars at the site of the tumor, but almost normal tissue, as if there was no disease.

Diagnostics

The diagnosis is made on the basis of characteristic symptoms and is confirmed by additional examination data, which makes it possible to identify the pathological process at an early stage.

- Laboratory research:

- general blood test - signs of inflammation are revealed - accelerated ESR, increased leukocyte content; signs of anemia;

- biochemical analysis - an imbalance of serum proteins is revealed: the amount of alpha globulins decreases and the amount of gamma globulins increases; C-reactive protein (CRP) is detected in the blood - a sign of an inflammatory process;

- Immunological tests are a marker that allows you to distinguish between seronegative and seropositive types of RA:

- rheumatoid factor (antibodies to IgG) is not detected or its titers are insignificant; the presence of rheumatoid factor indicates seropositive RA;

- antibodies to cyclic citrulline-containing peptide (anti-CCP, ACCP) may be positive and then this confirms the diagnosis of seronegative arthritis; citrulline is a metabolic product that is normally completely excreted from the body; in RA, enzymes are secreted that integrate citrulline into tissue proteins and convert it into a foreign protein - antigen; The immune system produces antibodies to this antigen.

- Instrumental diagnostics:

- x-ray of joints;

- Ultrasound;

- MRI or CT are the most informative diagnostic methods;

- if necessary, arthroscopy - endoscopic examination of the affected joint.

Crunching in joints - when to worry

Intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid

Scope of application of cytostatics

Cytostatics are used for all malignant tumors, not excluding diseases of the blood and lymphatic tissue, tumors of the brain and gonads. Cyclophosphamide and antimetabolites in disproportionately lower doses than in oncology are used in rheumatology.

Each cytostatic drug has its own spectrum of antitumor activity, for example, doxorubicin and fluorouracil work great for breast cancer, but are ineffective for small cell lung cancer. Chemotherapy for intestinal carcinomas is not possible without fluorouracil, and doxorubicin is useless for them.

Indications and contraindications for the use of cytostatics

Antitumor drugs are used only with morphological confirmation of the diagnosis. Processes are not recognized as malignant if the morphological (histological) conclusion indicates “suspiciously for...”, there must be an accurate and 100% answer. If suspected, additional research is necessary - a repeat biopsy, IHC and even genetic research.

A global contraindication is predicted intolerance to chemotherapy in the presence of severe concomitant diseases or a serious condition caused by a malignant disease. When “the game is not worth the candle” and drug intervention threatens serious complications and death.

You cannot use drugs if they are known to be ineffective - outside the spectrum of activity.

Temporary contraindication: inflammatory and infectious diseases, residual complications after the previous course of treatment.

Today, the choice of antitumor drugs is so wide that it is not difficult to choose the optimal drug or even combination. However, if at least two lines of therapy are ineffective and the condition is progressively worsening, a third chemotherapy option is not always advisable.

Therapeutic measures

Is it possible that seronegative rheumatoid arthritis can be cured? It is impossible to cure completely, but in the treatment of seronegative forms of RA, as in the treatment of any other chronic disease, they try to achieve long-term remission. The longer it is, the higher the patient’s quality of life.

Modern treatment technologies make it possible to achieve unlimited remission. But the patient should always remember that a relapse is possible and follow the doctor’s recommendations to prevent exacerbations.

Treatment of seronegative rheumatoid arthritis should be comprehensive and include:

- compliance with the motor regime, exercise therapy;

- proper balanced nutrition;

- drug therapy;

- blood purification;

- traditional medicine prescribed by a doctor;

- physiotherapeutic procedures;

- orthopedic correction;

- surgery.

Treatment of seronegative rheumatoid arthritis

Regime, exercise therapy, diet

Seronegative rheumatoid arthritis requires a conscious attitude to the daily routine and physical activity. Restriction of movement is necessary only during exacerbations of seronegative arthritis. As soon as the patient’s condition improves, he is prescribed physical therapy (physical therapy) complexes with a gradually increasing load. If this is not done, blood circulation will be impaired, the mobility of the limb will decrease, the risk of developing ankylosis will increase, the muscles will lose their strength and decrease in volume.

In addition to exercise therapy, during remission it is recommended to walk, swim, and ride a bike more. Traumatic movements - jumping, football, etc. - are contraindicated.

It is important to eat right; your diet should contain a sufficient amount of proteins, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins and minerals. Food should be enriched with calcium and vitamin D (cottage cheese, cheese, kefir, fish oil) - this is necessary to prevent osteoporosis.

Drug therapy and traditional medicine

Medical treatment of seronegative rheumatoid arthritis begins with the use of anti-inflammatory drugs to relieve inflammation and associated pain. Patients are prescribed medications from the group of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These are Diclofenac, Indomethacin, Ibuprofen, Nimesulide, Meloxicam, etc. They are prescribed internally or in the form of external agents - gels, ointments, creams.

In severe cases of the disease, glucocorticosteroid hormones (GCS) are prescribed - Hydrocortisone, Betamethasone, Dexamethasone, etc. They are taken orally, injected or directly into the joint cavity. They can also be used externally in the form of ointments and creams. GCS perfectly relieve signs of inflammation, but have serious side effects, so they are prescribed only when indicated and in short courses for several days.

The next group of drugs is immunosuppressants - drugs that suppress excessive immune activity - Methotrexate, Sulfasalazine, Cyclophosphamide, Cyclosporine, Leflunomide. Seronegative rheumatoid arthritis often does not respond to the use of a particular drug and is more difficult to treat than seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Therefore, doctors often use combination basic therapy, using several medications at once, monitoring the patient’s condition and laboratory parameters.

The most modern drugs for suppressing the activity of seronegative arthritis are biological agents. Drugs in this group belong to biologically active substances (antibodies, cytokines) that act directly on broken parts of the immune system. These drugs include Rituximab, Tocilizumab, Abatacept. This is an effective, but quite expensive therapy that can take treatment to a higher level.

To enhance the effect of drug therapy for seronegative arthritis, the use of individually selected medications is combined with traditional medicine. This can also reduce the large drug burden on the patient's body.

Blood purification

In case of severe intoxication and a widespread process, procedures such as hemosorption and plasmapheresis, which rid the blood of toxic substances, can be used.

Physiotherapeutic procedures

Physiotherapy is added at all stages of treatment of seronegative rheumatoid arthritis. Electrophoresis with NSAIDs and GCS helps eliminate inflammation and pain; magnetic and laser therapy can be used to suppress destructive processes in tissues. Physiotherapy courses speed up the recovery process and reduce the risk of complications.

Orthopedic correction

A patient with seronegative arthritis is taught to hold the affected limb in a physiologically correct position to reduce the risk of deformity. For this purpose, special devices are used to straighten the limb - orthoses. They are worn for several hours a day, removed during exercise. Orthoses help treat joint dysfunction in various forms of rheumatoid arthritis.

Surgical operations

Treatment methods for seronegative rheumatoid arthritis

It is rarely used, only if functional joint failure is diagnosed. Endoprosthesis replacement or resection of part of the joint capsule is performed. The operation helps to cure the patient even with severe lesions.

Side effects of cytostatics

Toxic reactions are caused by damage to normal tissues, which are usually very sensitive to cytostatics:

- blood cells, which is clinically manifested by changes in tests, most often leukopenia and neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and much less often - anemia;

- bone marrow gradually slows down the rate of restoration of hematopoietic sprouts, active tissue is replaced by connective and fatty tissue, and in blood tests the level of all formed elements decreases;

- mucous membranes react with necrosis with rejection, which is manifested by stomatitis, colitis, enteritis, pneumonitis and inflammation of the venous endothelium;

- the gonads respond by disrupting spermatogenesis and stopping menstruation;

- skin appendages - hair falls out, nails become coarser and change their structure.

The drug may have not only general, but also individual toxic manifestations, in which nerve cells or renal tubules, hepatocytes or muscle fibers of the heart selectively die. Sensitivity to drugs is very individual, and the spectrum and severity of adverse reactions also vary.

Narrow window of opportunity

Elena Nechaenko, AiF Health: How many Russians suffer from rheumatoid arthritis, the most common inflammatory rheumatic disease?

Evgeniy Nasonov : Today we have more than 800 thousand such patients, and at least 30 thousand new cases of illness are registered annually. The disease can begin at any age, but usually occurs between 35 and 55 years of age, more often in women. This disease has no cure, but it can be successfully controlled. To do this, it is necessary to begin treatment with drugs with proven effectiveness as early as possible. After all, the period of time during which such therapy gives the maximum effect (the so-called window of opportunity) is quite short. If you miss time, the most modern medications will not be as effective as at the beginning of the disease. It is also important to realize that self-medication is unacceptable, it can lead to fatal consequences.

– What manifestations of the disease most often begin?

– This is usually pain, swelling and stiffness in the joints of the hands and feet, and there may be a slight fever, general weakness, fatigue and depression.

Rheumatologist: “Rheumatoid arthritis can occur at any age” Read more

Mechanism of action of cytostatics

Two driving mechanisms:

- changes in the structure of DNA, including abnormal twisting that prevents the strands from diverging during division, as well as repair disorders - restoring the continuity of the strand when damaged;

- cell division disorder is a disorder in the formation of the cell spindle, which separates chromosomes into daughter cells, typical of herbal preparations.

Not only each group, but also each cytostatic has its own mechanism of antitumor action, or rather, several mechanisms of damage, most of which are unknown.

What cytostatics are most often prescribed?

Only those that actively treat this malignant nosology and are optimal in a specific clinical case are prescribed. The widest range of activity is found in the antibiotic doxorubicin, alkylating platinum derivatives and cyclophosphamide, plant taxanes and the antimetabolites fluorouracil and methotrexate.

Clinical guidelines suggest using the most effective combinations of drugs with an optimal balance of effectiveness and toxicity. In our clinic, we select cytostatic therapy individually, depending on the sensitivity of the cancer tumor. We do not guarantee the absence of toxicity, but we can minimize its manifestations and accelerate the restoration of normal tissues.

Book a consultation 24 hours a day

+7+7+78