The elbow joint belongs to the group of complex ones, since it combines three joints of three different bones: the radius, ulna and humerus. This is why the anatomy of the human elbow joint is incredibly complex, because it must be considered in the context of three different joints united by one articular capsule.

All kinds of diseases, developmental disorders and injuries can also affect one of the areas of the elbow or all at once - it depends on the severity and location of the pathology. In order to consistently understand this issue, you should study in detail each component of the elbow, its features and structure - only in this way can you understand the basic anatomy of this most important joint of the upper limb.

Elbow joint: anatomy and bone functions

The human elbow is formed by three bones of different volume and density - the ulna, radius (their proximal part) and the humerus (respectively, the distal part).

Brachial bone

This bone is a clear example of the dense and incredibly strong tubular bones of the human body, the shape of which smoothly transitions from perfectly round at the top to triangular at the bottom. Such features allow the distal end to ideally articulate with the bones of the forearm, the medial end to adjoin the ulna, and the lateral end, respectively, to the radius. At the same time, the medial surface has a smoother structure, and the lateral surface is spherical, which largely explains the physiology and characteristics of the trajectory of the elbow.

The surface of the humerus is covered with pits and depressions of various shapes and sizes, thanks to which a tight interaction of the elements of the elbow joint is formed. So, for example, above the medial surface there are small holes into which, when bent, the processes of the ulna - the coronoid and ulna - fall. These processes seem to fix the elbow in the grooves, supporting the joint capsule and protecting it from injury. In the medial and lateral epicondyles, which are quite easy to palpate at the distal end of the bone, there are attachment points for muscle fibers and ligamentous apparatus. And the spiral groove serves as the location of the radial nerve, which innervates the tissues of the upper limb.

Elbow bone

The triangular ulna bone is more voluminous and powerful than the radial bone. At the upper end it has a significant thickening with a trochlear notch, to which the humerus tightly adjoins, as if enveloping it. The lateral edge, accordingly, is adjacent to the radius.

The surface of the ulna is also heterogeneous, and for good reason. On the anterior and posterior surfaces of the trochlear notch there are two processes that limit the mobility of the elbow and ensure the normal physiology of the joint - the coronoid and ulnar. Following them is a special tuberosity, which is necessary for a stronger attachment of the brachial muscle. And below, at the distal end, there is a head with another process - the medial styloid, thanks to which the articulation of the ulna and radius bones is partially supported.

If desired, the anatomy of the ulna can be examined not only in pictures, but also on your own hand - this bone can be easily and painlessly felt under the skin along its entire length, starting with the dense muscular skeleton in its upper part and ending with the tendon bursa in the lower part. A certain anatomical structure, coupled with an adequate amount of muscle and fatty tissue of the arm, allows us to even see the head of the bone, which normally protrudes slightly on the inner back surface. All this greatly facilitates the identification of injuries and structural anomalies of the upper limb - with the proper skill of the physician, a correct diagnosis can be made even before an x-ray, which is required to clarify the clinical picture rather than for diagnosis.

Radius

The radius bone, together with the ulna, forms the forearm, however, unlike the latter, it is less durable and has a thickened lower rather than upper section. This structure allows you to achieve balance in the structure of the forearm and elbow joint. The small diameter and vulnerability of this bone requires special protection from the body, therefore, as a rule, it is surrounded throughout its entire length by well-developed muscle fibers, securely fixed in the pits and tuberosities. All this allows not only to prevent the occurrence of injuries and damage, but also to develop mobility, slightly expanding the capabilities of the normal physiology of the elbow joint.

Muscles acting on the elbow joint.

Brachialis muscle, m. brachialis.

Origin: Originates from the lower part of the humerus

Attachment: Attaches to the ulna tuberosity

Function: Flexes the forearm, tightens the capsule of the elbow joint

Triceps brachii muscle, m.triceps brachii.

biangular, located on the posterior surface of the shoulder, has three heads: long, lateral and medial:

caput longum - tuberculum infraglenoidalis scapulae;

caput laterale - posterolateral surface of the humerus;

caput mediale - posterior surface of humerus.

All three heads unite into a common tendon, which attaches to the olecranon process of the ulna.

Origin: Begins with three heads: long - from the subarticular tubercle of the scapula, medial and lateral - from the humerus

Insertion: Attached to the olecranon process and capsule of the elbow joint

Function: Extends the forearm, pulls the shoulder back, brings the shoulder towards the body

Brachioradialis muscle, m. brachioradialis.

Origin: Originates from the humerus and the lateral intermuscular septum

Insertion: Attached to the distal end of the radius

Function: Flexes the forearm at the elbow joint, rotates the radius, is positioned in the middle position between pronation and supination

Muscles acting on the wrist joint.

Flexor carpi ulnaris, m. flexor carpi ulnaris

Origin: Begins with the humeral head from the internal epicondyle of the humerus, the coronoid process of the ulna and fascia, the ulnar head from the ulna

Attachment: Attaches to the pisiform, hamate and 5th metacarpal bones

Function: Flexes the wrist, adducts the hand

Extensor carpi ulnaris, m. extensor carpi ulnaris

Origin: Starts from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus and fascia of the forearm

Attachment: Attached to the base of the 5th metacarpal bone

Function: Extends and adducts the hand

Radial flexor carpi (m. flexor carpi radialis)

Origin: Originates from the internal axillary of the humerus, from the fascia of the forearm

Attachment: attaches to the base of the 2nd metacarpal bone

Function: Flexes the wrist and participates in pronation of the hand

Long palmar muscle (m. palmaris longus)

Origin: Starts from the internal epicondyle of the humerus

Attachment: Attached to the palmar aponeurosis

Function: Participates in flexion of the hand, strains the palmar aponeurosis

Extensor carpi radialis longus (m. extensor carpi radialis longus)

Origin: Originates from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, the lateral intermuscular septum of the shoulder

Attachment: Attached to the base of the 2nd metacarpal bone

Function: Slightly flexes the forearm, extends the hand, abducts the hand laterally

Extensor carpi radialis brevis (m. txtensor carpi radialis longus)

Origin: Begins from the lateral subcondyle of the humerus and the fascia of the forearm

Attachment: Attached to the dorsum of the base of the 3rd metacarpal bone

Function: Extends the hand and abducts it

Finger flexors:

Superficial digital flexor (m. flexor digitorum superfacialis)

Origin: Originates from the medial axilla of the humerus, the coronoid process of the ulna of the proximal radius

Attachment: Attached to the middle phalanges of 2-5 fingers

Function: Participates in flexion of the middle phalanges of 2-5 fingers, in flexion of the hand

Flexor digitorum profundus (m. flexor digitorum profundus)

Origin: Originates from the upper two-thirds of the anterior surface of the ulna and the interosseous membrane of the forearm

Insertion: Attached to the distal phalanx of the thumb

Function: Flexes the distal phalanx of the thumb and hand

Abductor pollicis longus (m. abductor pollicis longus)

Origin: Begins on the posterior surface of the ulna and radius, interosseous membrane of the forearm

Attachment: Attached to the base of the 1st metacarpal bone

Function: Abducts the thumb and the entire hand

Extensor pollicis longus (m. extensor pollicis longus)

Origin: Originates from the posterior surface of the ulna, interosseous membrane of the forearm

Attachment: Attached to the distal phalanx of the thumb

Function: Extends the thumb

Extensor carpi radialis longus (m. extensor carpi radialis longus)

Origin: Originates from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, the lateral intermuscular septum of the shoulder

Attachment: Attached to the base of the 2nd metacarpal bone

Function: Slightly flexes the forearm, extends the hand, abducts the hand laterally

Extensor carpi radialis brevis (m. txtensor carpi radialis longus)

Origin: Begins from the lateral subcondyle of the humerus and the fascia of the forearm

Attachment: Attached to the dorsum of the base of the 3rd metacarpal bone

Function: Extends the hand and abducts it 42. Muscles acting on the hip joint. Iliopsoas muscle, m. Iliopsoas. Origin: iliac fossa, spinailiacaanteriorsuperioretinferior – 1, lumbar vertebrae – 2. Attachment: trochanterminor. Function: flexes and rotates the hip.

Gluteus maximus muscle, m. gluteusmaximus,

Beginning: posterior gluteal line of the ilium, sacrum, coccyx, sacrotuberous ligament (lig. sacrotuberale). Attachment: tuberositas glutea.

Function: extends, abducts and rotates the thigh outward.

Gluteus medius muscle, gluteusmedius,

Origin: outer surface of the ilium.

Attachment: greater trochanter. Function: abducts the thigh, rotates it outward, holds the pelvis and torso in an upright position.

Gluteus minimus muscle, t. gluteusminimus

,

Origin: outer surface of the ilium between the anterior and inferior gluteal lines.

Attachment: greater trochanter.

Function: abducts the thigh, rotates it outward, holds the pelvis and torso in an upright position.

Tensor fasciae lata, tensorfasciaelatae,

Origin: superior anterior iliac spine. Insertion: tibial tuberosity.

Function: flexes, abducts and rotates the thigh, inwardly extends the lower leg, rotates it outward.

Quadratus femori muscle

Origin: ischial tuberosity.

Insertion: intertrochanteric ridge. Function: adducts the hip and rotates it outward.

External obturator muscle, i.e. obturator externus.

Beginning: the outer surface of the obturator membrane, limiting the opening of the bone.

Attachment: fossatrochanterica, articular capsule. Function: rotates the thigh outward 43. Muscles acting on the knee joint.

Sartorial muscle, m. Sartorius.

Beginning: spina iliaca anterior superior. Attachment: tuberositastibia.

Function: adducts the hip and rotates it outward.

Vastus intermedius muscle, m. vastus intermedius

Biceps femoris muscle

long head – 1, short head – 2.

Origin: ischial tuberosity – 1, lateral lip of linea aspera –2.

Attachment: caputfibulae.

Function: extends and extends the thigh, rotates it outward - 1, bends the lower leg and - 1.2 rotates it outward.

Semitendinosus muscle, m. semitendinosus. Origin: ischial tuberosity.

Insertion: tibial tuberosity.

Function: extends, adducts and internally rotates the thigh, stretches the capsule of the knee joint.

Semimembranosus muscle, m. semimembranalis.

Origin: ischial tuberosity. Insertion: medial condyle of the tibia.

Function: extends, adducts and internally rotates the thigh.

Thin muscle, m. gracilis. Origin: inferior branch of the pubic bone, near the symphysis.

Insertion: fascia of the leg, near the tibial tuberosity.

Function: adducts the thigh, flexes the tibia.

Sections forming the elbow joint

Since the elbow is a complex joint and consists of three bones connected in pairs to each other, in anatomy it is customary to distinguish three interconnected sections of this joint, surrounded by one articular capsule:

- Shoulder-ulnar joint

. It is formed by the trochlear structure of the humerus and the notch of the ulna, which normally connect and fit tightly together like puzzle pieces. It allows you to move your forearm, bending and extending your arm. - Humeral joint

. This articulation is formed at the point of contact of the articular fossa of the radial and condylar heads of the humerus. In shape it is classified as spherical, however, the features of the anatomical structure allow movements not in three, but only in two projections (flexion - extension plus rotation), since the third is limited by the presence of the adjacent ulna and a strong ligamentous apparatus. - Proximal radioulnar joint

. The cylindrical articulation of the radius and ulna bones supports the capabilities of the elbow, ensuring mobility of the arm along the longitudinal axis, that is, its rotation.

Bones and joints of the elbow joint

The distal epiphysis of the humerus has a trochlea and a condylar head. The proximal end of the ulna has the trochlear and radial notches. The radius has a head and an articular circumference, which can be seen by looking at the drawing. The ulnohumeral joint is formed by the articulation of the trochlea of the humerus and the trochlear notch of the ulna. The humeroradial joint is formed by the articulation of the head of the condyle of the humerus with the articular circumference of the radius. And the proximal radioulnar joint is formed by the articulation of the radial notch of the ulna and the head of the radius.

The elbow joint can move in two planes:

- Flexion and extension (frontal plane);

- Rotation (vertical plane). This movement is provided only by the humeroradial joint.

As can be seen in the anatomical atlas with photos, the articular capsule surrounds all three joints. It originates in front above the edge of the radial and coronoid fossae, on the sides almost at the edge of the trochlear and condyle of the humerus, behind just below the upper edge of the olecranon process and is attached to the edge of the radial and trochlear notches on the ulna and to the neck of the radius.

Blood supply and innervation of the adjacent area

Complete nutrition of the elbow joint is provided by the powerful blood network that surrounds it. Arterial blood enters the muscle fibers adjacent to the articular surface from the superior and inferior collateral ulnar arteries, as well as the recurrent, median and radial arteries. Having enriched the cells and tissues with oxygen and nutrients necessary to maintain physiological functions, it is sent through the veins of the same name to the venous basins of the upper extremities - the brachial, ulnar and radial. The lymph flow of the elbow joint passes in a similar way, moving through the lymphatic vessels to the elbow lymph nodes.

The innervation of the capsule that unites the sections of the elbow joint is carried out by the largest nerve fibers of the arm - the branches of the ulnar, radial and median nerves. This explains the high sensitivity of the tissues adjacent to the elbow and the particular pain of the resulting injuries.

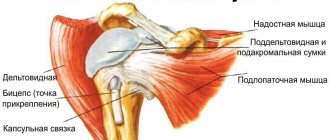

Muscles and ligaments of the elbow joint

The structural features and enormous functionality of the upper limbs are largely possible due to the anatomy of the human elbow joint. It is this joint that maintains mobility and ensures full activity of the upper limb, so the muscular-ligamentous apparatus of the elbow simply cannot have a simple structure. Let's consider each of these elements in order to understand the relationship between the anatomical structure and physiological capabilities of the elbow joint.

Muscular apparatus

Greater strength, physical capabilities and flexibility of the arm are provided largely due to the muscles acting on the elbow joint. Since the movements allowed in the elbow affect two planes - flexion/extension and pronation/supination - all muscle fibers can be divided into 3 significant groups:

1. Elbow flexor muscles

Such a movement is possible due to the contraction of muscle fibers, which, as it were, tighten the forearm, reducing the angle formed by it and the shoulder. The most powerful flexor of the upper limb is the biceps, located parallel to the humerus. In addition, this largest muscle is able to partially participate in supination of the forearm and rotation of the palm.

Additional muscles that flex the arm are the brachialis and brachioradialis. They (although they are considered auxiliary) in case of injury to the biceps are able to compensate for lost functions by performing full range of arm movements.

2. Extensors of the upper limb

Antagonist flexor muscles perform the exact opposite function, increasing the angle between the free end of the forearm and the shoulder of the upper limb. These include the triceps (triceps) and olecranon muscles, as well as the tensor fascia of the forearm. The triceps, like the biceps, is parallel to the humerus, but is located not anteriorly, but posteriorly, from the olecranon to the scapula. Together with the ulnar muscle fibers, it contracts and causes extension of the forearm in the elbow joint until the olecranon process fixes the humerus (the maximum allowable physiological extension of the arm).

3. Rotator muscles

This group is responsible for arm rotation - pronation and supination. The pronators that rotate the forearm in and out at the elbow joint include the pronator teres and quadratus muscles, as well as partly the brachioradialis muscle. And the second group - the instep muscles, which perform movements with the forearm from the inside - combines the instep muscle, the brachioradialis muscle and the biceps.

Elbow ligaments

The general joint capsule surrounding the elbow is not strong enough to hold all the large bones of the upper limb in a single joint, especially on the inside. High loads on the arms during physical work and sports training would invariably lead to damage to the elbow if it were not for the strong ligamentous apparatus that reliably holds the elbow and ensures its limited mobility. It includes the following fibers:

- The radial collateral ligament connects the epicondyle of the humerus and the head of the radius, then splits into two bundles and, enveloping the head in a kind of ring, is attached to the radial notch of the ulna. During life, the upper part of this ring gradually intertwines with the tendons responsible for extension, partially fulfilling their function and preventing overstretching; and the deep fibers form a single structure with the annular ligament.

- The ulnar collateral ligament extends from the medial epicondyle of the humerus to the trochlear notch of the ulna. Together with the radial collateral ligament, this ligament limits the mobility of the elbow, preventing lateral movements.

- The annular ligament is a kind of “sealing ring” that covers the articular circumference of the head of the radius, additionally fixing it at the ulna.

- The quadrate ligament connects the ulna bone to the radial neck, reliably fixing them to each other and preventing divergence or hyperextension.

Speaking about the ligamentous apparatus of the human elbow joint, it is impossible not to mention the interosseous membrane - a special structure that, although anatomically, does not belong to the ligaments, but performs a single function with them, fixing the bones of the forearm in the sections of the joint. It fills the small gap formed by the surfaces of the radius and ulna bones and forms a strong radioulnar syndesmosis. The tightly woven fibers of this membrane have special openings through which the vessels and nerves of the elbow pass, and the edges serve as attachment points for some muscle fibers.

Anatomy of the elbow joint[edit | edit code]

Bones of the elbow joint

Bone anatomy[edit | edit code]

Anatomy of the Elbow Joint

The elbow joint is the articulation of three bones: the humerus, the ulna, and the radius. The shoulder-elbow joint is a trochlear joint; it is formed by the trochlea of the medial condyle of the humerus and the lunate notch of the ulna. The ulnar and coronoid processes, which deepen the semilunar notch, contribute to an increase in the area of the articular surface. The humeroradial joint is formed by the head of the radius and the head of the condyle of the humerus. The joint between the ulna and radius is formed by the head of the radius and the radial notch of the ulna. These joints, together with the ligamentous and muscular apparatus, provide flexion and extension at the elbow joint, as well as pronation and supination of the forearm.

Biomechanics of the elbow joint on x-ray

Anatomy of ligaments[edit | edit code]

Ligaments of the elbow joint

Ligaments are thickened areas of the joint capsule that provide stability to the joint. The elbow joint is surrounded by a complex network of ligaments. The lateral part of the joint is strengthened by a complex of four ligaments: the radial collateral ligament, the annular ligament of the radius, the accessory lateral collateral ligament, and the lateral ulnar collateral ligament. The radial collateral ligament begins from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus and, expanding in the distal direction, merges with the deep fibers of the annular ligament of the radius, strengthens the latter and ensures stability of the elbow joint under varus load (adduction of the forearm). The annular ligament of the radius attaches to the anterior and posterior surfaces of the radial notch of the ulna, forming a ring around the head and neck of the radius; it provides stability during pronation and supination. The distal end of the accessory lateral collateral ligament is attached to the tubercle of the supinator crest of the ulna; The proximal end of the ligament merges with the fibers of the annular ligament of the radius. The lateral ulnar collateral ligament is attached with its proximal end to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, and its distal end to the crest of the supinator of the ulna under the fascia of this muscle. It provides stability to the lateral aspect of the elbow joint, reduces stress during forearm rotation, and supports the radial head posteriorly.

The medial part of the elbow joint is also strengthened by a ligamentous complex. It includes the anterior, posterior and transverse (Cooper's ligament) portions of the ulnar collateral ligament. The anterior portion of the ulnar collateral ligament is of greatest importance in counteracting the valgus load on the elbow joint (forearm abduction). It is attached to the medial epicondyle of the humerus and to the tip of the coronoid process and provides static and dynamic stability of the elbow joint during throwing movements, accompanied by flexion from 20 to 120°. The posterior portion of the ulnar collateral ligament strengthens the medial sections of the elbow joint during pronation. Its attachment points are the lateral epicondyle of the humerus and the olecranon process. The humeroulnohumeral joint, radial and ulnar collateral ligaments are the three main stabilizing structures of the elbow joint. Damage to any of them leads to an increase in the load on secondary stabilizing structures, which include the head of the radius, the anterior and posterior parts of the capsule of the elbow joint, the attachment points of the anterior and posterior groups of the forearm muscles, as well as the ulnaris, triceps and brachialis muscles.

Muscle anatomy[edit | edit code]

Muscles of the elbow joint

To ensure precise coordinated movements in the joint, balanced muscle contraction is necessary. Movement in the elbow joint is provided by the following muscles. Along the anterior surface, the brachialis muscle is attached to the coronoid process of the ulna, while its antagonist, the triceps muscle, is attached by a flat broad tendon to the olecranon process of the ulna. The extensor muscles of the superficial layer of the posterior muscle group of the forearm originate from the lateral epicondyle of the shoulder; these include the extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor digitorum, and flexor carpi ulnaris muscles. On the other side of the distal epiphysis of the humerus, from the medial epicondyle and the medial epicondylar crest, the anterior group of muscles of the forearm (flexors and pronators) originates. It includes the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, flexor digitorum superficialis, and flexor carpi ulnaris muscles.

Nerves[edit | edit code]

Innervation of the muscles of the elbow joint is carried out by three main nerves of the free lower limb: the radial nerve (including the posterior interosseous), passing in front and lateral to the joint, the median nerve, passing along the midline in front, and the ulnar nerve, passing along the posteromedial surface of the elbow region. The radial nerve is formed by the posterior bundle of the brachial plexus (roots C6, C7 and Thl); it innervates the triceps muscle, the supinator muscle, and the extensors of the wrist and fingers. The ulnar nerve is formed from the medial bundle of the brachial plexus (C7 and Thl roots) and innervates the flexor carpi ulnaris, deep digital flexors and lumbrical muscles of the ring and little fingers, dorsal and palmar interosseous muscles, the adductor pollicis muscle, as well as the muscles of the eminence of the little finger ( Opposite minimi muscle, adductor digiti minimi, and flexor digiti minimi). The median nerve is formed by the lateral and medial fascicles of the brachial plexus (roots C6, C7 and Thl) and innervates palmaris longus, pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, deep flexors of the index and middle fingers, flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor pollicis longus, pronator quadratus, lumbricals muscles of the thumb and index finger, as well as the muscles of the eminence of the thumb (opponus pollicis, abductor pollicis and flexor pollicis).

Compression of these nerves, usually reversible, is a common cause of elbow pain. The radial nerve may be compressed by the fibrous arch of the lateral head of the triceps muscle, the arcade of Froese, the insertion of the extensor carpi radialis brevis, and adjacent structures. Compression of the ulnar nerve is possible in the area of the supracondylar process of the humerus, in the area of the arcade of Straders, at the insertion of the flexor carpi ulnaris, in the ulnar tunnel of the wrist (see section “Cubital tunnel syndrome”). The median nerve may be compressed by the supracondylar process of the humerus and its attachments, the ligament of Straders, the arch of the superficial flexor digitorum, the biceps brachii aponeurosis, or the pronator teres muscle. Compression of the median nerve is also possible in the carpal tunnel.

Physiology of the human elbow joint

The normal physiology of the human elbow joint implies fairly extensive mobility: even without special training, the bones of the forearm and shoulder can rotate 90°, bend up to 150° and extend another 10° in the opposite direction (that is, as if beyond the elbow). Moreover, these degrees are not the limit - with certain skill and careful training, the mobility of the elbow joint can be increased several times, clearly demonstrating the almost limitless capabilities of the human body.

It should be borne in mind that such functionality requires special attention when loading the elbow joint. Although it belongs to the group of hanging ones and does not formally serve as a support, the size and number of loads does not decrease from this. This is particularly due to physical work, weight lifting, sports training and other activities that involve the upper extremities. As a result, any careless movement performed without proper preparation and warming up of the ligamentous-muscular system can be fraught with a painful elbow injury that requires long-term treatment. Therefore, you should take care of your own body and regularly strengthen it with gradually increasing loads as part of physical exercises - only in this way can you develop your elbow joints, making your arms truly strong, resilient and flexible.