What is rheumatoid arthritis and what are the causes?

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects joints and various organs. The most common symptom is pain, stiffness, or swelling in the joints of the hands and feet, but inflammation can also affect other joints. Without treatment, the disease most often leads to joint destruction and severe disability, as well as damage to multiple organs and early death. Early initiation of effective treatment suppresses the progression of the disease, prevents complications of the disease and enables normal functioning.

What factors can affect the prognosis?

While the prognosis for people with RA is difficult to predict, several factors may have an impact. This:

- the presence of complications and systemic symptoms;

- person's age;

- progression of the condition upon diagnosis;

- overweight or obesity;

- genetic factor;

- lifestyle factors such as smoking and sedentary lifestyle.

A study in people with a genetic predisposition to RA found that smoking is a significant risk factor for developing the disease. Smoking causes further inflammation, which can worsen the condition and increase the risk of complications such as respiratory disease and heart disease.

As with many other diseases, early diagnosis of RA can lead to significant improvement. Early stages of the disease tend to be associated with less inflammation, which is easier to control with anti-inflammatory drugs. Treatment at this stage can prevent irreversible joint damage and minimize the impact of RA on quality of life.

A later diagnosis leads to a chronic course of the disease, which is difficult to treat. There is also an increased risk of permanent joint damage.

Causes of rheumatoid arthritis

The essence of the disease is the inflammatory process that begins inside the joint. An unknown factor stimulates the synovium lining the joint to produce an inflammatory response. It grows and destroys adjacent structures (cartilage, bones, ligaments, tendons). Symptoms of this initially include pain and swelling, followed by irreversible destruction and loss of motion of the joint.

Picture 1. Localization of joint changes in rheumatoid arthritis

The causes of RA are not fully understood. Most likely, the coexistence of many factors is necessary for the development of the disease. The most important of them are:

- hereditary predisposition - there is a predisposition to the development of RA in close relatives, but the genetic factor itself does not cause the disease - therefore, the presence of RA in a parent does not mean that the disease will develop in children, but the risk of development in them is 2-5 times higher

- defect of the immune system - leads to erroneous recognition of one’s own tissues as an “enemy” and the production of autoantibodies to destroy them; Several genes responsible for this process have been identified (including histocompatibility genes HLA DRB1).

- gender - women get sick about 3 times more often than men

- infection - some bacteria and viruses are suspected of playing a role in initiating the inflammatory response

- Smoking increases the risk of the disease and causes its more severe course.

- stress - in some patients the disease begins after severe stress

How does the disease progress?

Pain syndrome usually occurs with the development of a tumor around the painful joint

At first, the inflammatory process affects only one joint. The tissues around it begin to swell, turn red, and only after an indefinite period of time the patient begins to feel stiffness and pain. The disease can quickly spread to the second, third, etc. joints - literally in a few hours. But the onset of the inflammatory process is almost always invisible to humans.

The disease can affect two or three joints or spread to the arms, legs, spine and lower jaw. The most susceptible are precisely those joints that are actively loaded by a person or experience adverse effects (bruise, compression, hypothermia).

In arthritis, inflammation affects the synovium of the joint. It is the proteins of these tissues that the immune system begins to fight, mistaking them for foreign agents. This affects how long people live with rheumatoid arthritis. Associated symptoms also appear:

- lethargy, constant fatigue;

- the appearance of subcutaneous nodes (more typical for the elbow joints);

- increased body temperature;

- tearing and redness of the eyes;

- feeling of numbness in the limbs;

- weight loss;

- enlarged lymph nodes.

Among the first manifestations is morning stiffness: it is difficult for a person to bend/extend an arm or leg or move his fingers. The reason for this is the accumulation of inflammatory exudate during the person’s immobile state.

How does rheumatoid arthritis manifest?

In most patients, RA develops silently. It may take several weeks or even months before symptoms become bothersome enough to require medical attention. Less often we deal with the sudden development of the disease within a few days. Often, “general” flu-like symptoms appear first, such as weakness, low-grade fever, muscle pain, lack of appetite, and weight loss. They may precede or accompany “joint” symptoms. During illness, symptoms of damage to other organs may also appear.

Characteristic symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis

Joints

The disease typically affects the same areas on both sides of the body. Initially these are the small joints of the hands and feet, and, as the disease progresses, many other joints. An atypical (but possible) onset of the disease is inflammation of one large joint (eg, knee or shoulder) or spread of disease to many joints.

Figure -2. Early changes in rheumatoid arthritis

Symptoms of arthritis are:

• pain and stiffness - most unpleasant after waking up or after a period of immobility in the joint, when inflammatory fluid accumulates and tissue swelling occurs; characterized by morning stiffness, which in RA usually lasts more than an hour

• edema is the result of the proliferation of the synovial membrane, forming the so-called. pannus, may be accompanied by exudate caused by increased formation of inflammatory joint fluid,

Figure -3. Progressive changes in RA (numerous rheumatoid nodules visible over the joints)

• sensitivity of the joint to pressure – typical, for example, is a painful handshake when reaching out to a patient with RA

• limitation of mobility - the affected joint loses the ability to perform the entire range of movements; and if damage to the joint structures occurs as a result of inflammation and secondary degenerative changes, the impairment of joint function becomes irreversible

• joint deformation is a consequence of a long-term illness; (Fig. typical articular deformities in RA).

Extra-articular lesions

Rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic disease that affects not only the joints, but also many organs (especially RA with severe and long-term course). In addition to relatively common benign lesions such as rheumatoid nodules or sicca syndrome, severe complications leading to premature death (eg, stroke or myocardial infarction) can occur very rarely.

- Rheumatoid nodules are painless, subcutaneous nodules, most often located in the elbows, hand joints, and other places subject to pressure; can also occur in internal organs.

- Atherosclerosis - its accelerated development is the result of activation of inflammatory processes; complications of atherosclerosis are the leading cause of premature death in people with RA; in these patients, the risk of developing myocardial infarction and heart failure, sudden cardiac death or stroke is 2-3 times higher than in healthy people (see also: What is atherosclerosis, Coronary heart disease, Myocardial infarction).

- Heart - in addition to coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction as a result of the development of atherosclerosis, the following may develop: pericarditis, cardiomyopathy, damage to the heart valves - symptoms of these diseases are: chest pain, shortness of breath and decreased exercise tolerance.

- Vasculitis is a rare but serious complication of RA, leading to ischemia of various internal organs; Ulcerations of the fingertips and skin may also occur.

- Lungs - RA contributes to, among other things, pleurisy and interstitial pneumonia; these diseases cause a dry cough, shortness of breath and chest pain.

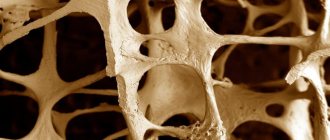

- Osteoporosis - both RA and the corticosteroids used in its treatment significantly accelerate the development of osteoporosis; Accordingly, early initiation of treatment to reduce the risk of bone fractures is important.

- Eyes - a common symptom is dryness syndrome caused by conjunctivitis, which is characterized by a feeling of sand or a foreign body under the eyelids; Less commonly, other structures of the eye are involved and vision problems occur.

- Nerves - the so-called so-called carpal tunnel syndrome; A rare but serious complication is spinal cord compression caused by subluxation of the vertebrae in the cervical spine - symptoms include headache, sensory disturbances (numbness, tingling, decreased pain sensitivity) and weakness or paresis of the limbs. This is a condition that requires urgent contact with a doctor.

- Kidneys - both the disease itself and the medications used can damage the kidneys; Regular monitoring of kidney function is important.

- Hematologic disorders —Moderate anemia as well as abnormal white blood cell counts occur during long-term illness. Exacerbations of the disease are characterized by an increase in the number of platelets. Enlarged lymph nodes and spleen are more common. RA increases susceptibility to infections and the risk of developing lymphomas.

Complications

In addition to serious joint deformation, arthritis can cause complications in other organs and systems

Complications of arthritis pose a significant danger, since they affect vital organs and systems. The following dangers of uncontrolled development of the disease are classified:

- Skin damage. The most common are rheumatoid nodules, which can appear gradually or suddenly. Thickening and hypotrophy of the skin, microinfarctions in the nail bed area may also be observed. It is impossible to give a definite answer to the question “how long do people live with psoriatic arthritis?” it all depends on the stage of the disease.

- Eye damage. This is where conjunctivitis most often appears. In more advanced cases, scleritis, which can lead to permanent vision loss. The most terrible consequence is Sjogren's syndrome - an autoimmune lesion of the lacrimal glands.

- Diseases of the cardiovascular system. They are characterized by various inflammatory processes in the heart: pericarditis (inflammation of the outer lining of the heart); mocarditis (inflammation of the middle lining of the heart); granulomatous inflammation of the valves.

- Damage to the nervous system. Manifested by the following diseases: cervical myelitis (inflammation of the cervical spinal cord); compression neuropathy (compression of nerve trunks); multiple vasculitis; sensory-motor neuropathy (decreased sensitivity of the affected nerves). Life expectancy for rheumatoid arthritis with such complications is low.

- Blood diseases. Common symptoms include thrombocytosis, anemia, and neutropenia (decreased neutrophil white blood cell count).

- Damage to the respiratory system. It manifests itself as interstitial lung disease, pleurisy (inflammation of the serous membrane), bronchiotolitis obliterans. The occurrence of rheumatoid nodules in the lung tissue is dangerous - they can cause a small rupture in the lungs and are characterized by coughing up blood.

- Diseases of the musculoskeletal system. Among them: generalized amyotrophy (disturbances in the nutritional processes of muscle tissue); bursitis, tendinitis, synovitis; damage to the cricoid-arytenoid joints of the larynx.

What to do if RA symptoms appear?

If pain and swelling of the joints develop, you should consult a doctor immediately. People with suspected RA should be monitored by a rheumatologist. Rapid diagnosis determines the effectiveness of treatment and, if started appropriately early, there is even the possibility of permanent remission of the disease.

During RA, complications may arise that require urgent medical intervention. Most often they can be prevented and effectively treated. Familiarize yourself with the symptoms that indicate complications of RA (see above).

Important

Contact your doctor immediately if you develop:

- exacerbation of the disease (increased pain, stiffness and swelling of the joints, subfibril conditions, weakness, weight loss) - requires more intensive treatment in order to suppress the activity of the disease as soon as possible

- any signs of infection, e.g. fever, cough, sore throat, burning sensation when urinating, weakness, feeling run down - RA patients have a reduced ability to fight infections (quick and effective treatment is required)

- if you have recently had a joint puncture, after which the intensity of pain, swelling, and temperature in the joint area or fever have increased, these may be symptoms of a joint infection that require prompt treatment; do not worry about joint pain, which goes away within 24 hours after the puncture (at this time you should limit the load on the joint)

- cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, decreased exercise tolerance - require urgent diagnosis in the direction of lung and heart diseases associated with RA

- any neurological symptoms (eg, sensory disturbances, weakness or paresis of the limbs, severe headache, visual disturbances) - may be a symptom of a stroke or compression of nerve structures

- abdominal pain, dark-colored stool (or bloody) - these may be symptoms of a peptic ulcer and bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract, which are a complication of treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

It is also extremely important to inform the doctor about the planned pregnancy (this applies to both women and men). Rheumatoid arthritis is not a contraindication to conception (and most women experience a temporary remission of the disease during pregnancy), but it should be scheduled in order to adjust treatment in a timely manner, since most drugs can harm the fetus.

How does a doctor diagnose rheumatoid arthritis?

Your doctor will diagnose rheumatoid arthritis by comparing typical symptoms with laboratory and imaging tests. The RA criteria used so far dated back to 1987 and were only applicable to advanced disease (meaning that an accurate diagnosis could only be made after long-term follow-up). In 2010, new criteria (ACR/EULAR) were developed, thanks to which it is possible to diagnose RA at the initial stage of the disease and begin treatment before irreversible joint destruction develops.

Laboratory research

Laboratory tests help in diagnosing RA, predicting the severity of the disease and monitoring its course.

- RF (rheumatoid factor) is detected in 70–80% of patients (the so-called seropositive form of RA); however, RF is also detected in healthy people and in other rheumatological diseases.

- ACCP (anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies) - their advantage is that they are found almost exclusively in RA; may appear earlier than symptoms of the disease, as well as in people with seronegative RA. A high titer of RF and ACCP indicates a severe form of the disease, with rapid destruction of joints and the appearance of extra-articular changes.

- Increased indicators of inflammation, e.g. ESR , CRP and changes in the general blood test , also serve to assess the activity of the disease.

Your doctor may also do other tests in your blood, urine, or joint fluid to rule out other joint diseases and to evaluate the functioning of various internal organs (eg, kidneys, liver).

Imaging studies

If RA is suspected, radiography (X-ray) of the hands and feet, and possibly other affected joints, is performed. Typical radiographic changes in RA are: soft tissue swelling and decreased bone density in the joint area, the presence of bone defects, narrowing of joint spaces, and in later stages, joint deformation.

At the onset of the disease, magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound are useful, which can detect inflammatory changes earlier than RG. In some cases (for example, when assessing the cervical spine), computed tomography is informative.

Current management of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis

Pharmacotherapy for RA has advanced significantly over the past 10–15 years. An earlier and more aggressive treatment strategy using traditional synthetic disease-modifying anti-inflammatory drugs (sDMARDs) and genetically engineered biological drugs (GEBPs) can change the clinical course of RA and slow or stop radiographic progression. Currently, the goal of RA treatment is remission [2] or (if this is not possible, for example, in the late stage of the disease) minimal disease activity, which allows, by controlling symptoms, to stop destruction, prevent disability and improve quality of life. It must be remembered that although inflammation is potentially reversible, damage to the joints (narrowing of the joint space due to cartilage degradation, bone erosion) is practically irreversible, therefore there is a need for aggressive treatment from the very beginning of the disease, for which the diagnosis must be established as early as possible.

Early diagnosis

Since in RA, as in many other immunoinflammatory diseases, there are no truly pathognomonic symptoms, including the results of laboratory and instrumental diagnostics, criteria-based diagnostic methods have been used since 1956 [4]. The latest version of the classification criteria for RA, a joint development of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), was published in 2010 [5]. These criteria are focused primarily on the early diagnosis of RA. The priority task for the authors was to identify patients in need of DMARDs.

According to the ACR/EULAR 2010 criteria, diagnosis is carried out in 3 stages:

1. It must be established that the patient has at least one swollen joint according to a clinical examination.

2. It is necessary to exclude other diseases that may be accompanied by inflammatory changes in the joints and for which such changes are more common than for RA. Differential diagnosis is required with various diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriatic arthritis, gout. In case of uncertainty, consultation with an expert rheumatologist is recommended.

3. You need to score at least 6 points out of 10 possible on 4 items that describe the features of the disease picture in this patient (Table 1).

A detailed description of the practical application of the ACR/EULAR 2010 criteria is given in our publication [4]. Testing of the ACR/EULAR classification criteria for RA has been conducted in several cohorts of patients with early arthritis. In general, the new criteria have demonstrated high sensitivity, but the possibility of overdiagnosis is discussed. In our group of patients with new-onset arthritis (n=413), high sensitivity and satisfactory specificity of these criteria were demonstrated (89 and 63%, respectively). It has been shown that the 2010 RA criteria best assess the condition of patients at a very early stage of the disease (up to 3 months), seronegative for rheumatoid factor (RF), and also with undifferentiated arthritis [6, 7].

Forecast assessment

After verifying the diagnosis of RA, it is necessary to identify the presence of unfavorable prognosis factors, which largely determine the aggressiveness of therapy. The presence of the following unfavorable prognosis factors should be assessed during the initial examination and taken into account when making a decision regarding treatment: the presence and titer of RF, the presence and level of antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptide (ACCP) and/or other antibodies to citrullinated peptides (ACP), functional impairment, major number of swollen and painful joints, early radiological erosions in the hands and feet, as well as erosions of the articular surfaces, pronounced bone marrow edema according to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the hands, erosions and a pronounced power Doppler signal according to ultrasound of the hands, signs of extra-articular lesions, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP). All these signs are associated with a more aggressive course of the disease and rapid progression of joint destruction [8–14]. Assessment of unfavorable prognosis factors is one of the components of clinical guidelines for the treatment of RA EULAR [15].

Principles of patient management and monitoring

The basic principles of managing patients with RA in a detailed form, the main modern rules were presented in 2010 in the international program “Treat to target” (T2T) [16]. The general principles of T2T are formulated as follows:

A. Treatment of RA should be based on the joint decision of the patient and the rheumatologist.

B. The main goal of treatment for a patient with RA is to ensure the highest possible health-related quality of life by controlling symptoms, preventing structural joint damage, and normalizing the patient's function and social abilities.

C. Suppressing inflammation is the most important way to achieve this goal.

D. Treating to target by assessing disease activity and tailoring therapy accordingly helps optimize RA outcome.

Based on general principles, the international committee has developed 10 T2T recommendations for treating RA to achieve the goal, based on scientific evidence and expert opinion:

1. The primary goal of RA treatment is to achieve a state of clinical remission.

2. Clinical remission is defined as the absence of signs of significant inflammatory activity.

3. Although the primary goal remains to achieve remission, based on the available scientific evidence, achieving low disease activity, especially in stable and long-term disease, may be considered an acceptable alternative treatment goal.

4. Until the treatment goal is achieved, drug therapy must be reviewed at least once every 3 months.

5. It is necessary to regularly assess and document data on disease activity: in patients with moderate/high activity - monthly, in patients with persistent low activity or in remission - less often (once every 3-6 months).

6. In everyday clinical practice, validated comprehensive indicators of disease activity, including assessment of joint condition, should be used to make treatment decisions.

7. In addition to the use of comprehensive measures of disease activity, clinical decision making must consider structural changes and dysfunction.

8. The desired goal of treatment should be maintained throughout the entire period of the disease.

9. The choice of (composite) disease activity measure and target parameters may be influenced by comorbidities, individual patient characteristics, and drug risks.

10. The patient should be sufficiently informed about the goal of treatment and the planned strategy to achieve this goal under the supervision of a rheumatologist.

Thus, in accordance with the T2T recommendations, when accepting a patient with RA, the doctor should:

- assess the severity of the patient’s condition and prognosis (activity, function, destruction, immunological parameters). This is facilitated by the correct formulation of the diagnosis according to the 2007 domestic clinical classification of RA [17, 18], which allows a compact form to describe the picture of the disease in a particular patient in sufficient detail and well substantiate the therapeutic approach (Table 2);

- Based on this, determine treatment goals;

- explain to the patient the principles of treatment and the possibilities of different medications, discuss the pros and cons of different treatment regimens, explain the key points: patients with RA need active treatment, and it is necessary to avoid “overtreatment” as well as “undertreatment”;

- RA treatment is not a one-time event, but a process during which treatment regimens change;

- resistance to DMARDs in full doses;

In the future, the doctor should monitor disease activity every 1–3 months. until low disease activity or (preferably) remission is achieved. The main control method at present is the use of the DAS28 activity index [18] (Table 2). Simplified indices – SDAI and CDAI [19], which more clearly define the state of clinical remission [20], are becoming increasingly widespread. In addition, to monitor the progression of joint destruction, radiography of the hands and feet is recommended every 12 months. (the gaps may be longer in long-term ill patients with radiographic stage 3–4). To verify structural disorders in joints and their dynamics, ultrasound and MRI of joints have recently been used, although the practical significance of these methods has not yet been fully determined.

Drug therapy for RA

The following groups of medications are currently used to treat RA:

1. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

2. Glucocorticoids (GC).

3. Synthetic DMARDs.

4. GIBP.

According to the recently published project of the EULAR group of specialists [21], in connection with the emergence of new classes of antirheumatic drugs, it has been proposed to distinguish within the group of s-DMARDs “regular” s-DMARDs (methotrexate (MTX), leflunomide (LEF), etc.) and targeted s-DMARDs. DMARDs, which are currently represented by the only registered drug (tofacitinib (TOFA)). Within the group of GIBPs, it is proposed to distinguish original GIBPs and biosimilars of GEBPs (“biosimilars”).

NSAIDs

NSAIDs are the first group of drugs prescribed for arthritis because they help control joint pain. NSAIDs inhibit the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX), which catalyzes the production of prostaglandins that cause inflammatory reactions (swelling, pain, vasodilation, etc.). COX exists in several isoforms, of which COX-1 is responsible for some protective reactions, primarily in the gastrointestinal tract, and COX-2 is activated during inflammation. NSAIDs are conventionally divided into non-selective, which inhibit COX-1 and COX-2 (diclofenac, aceclofenac, indomethacin, etc.), as well as selective, which primarily inhibit COX-2, so they have a better safety profile (celecoxib, etoricoxib). When choosing NSAIDs, it is necessary to take into account risk factors for the development of NSAID-associated gastropathy: high doses of NSAIDs, old age, Helicobacter pylori infection, a history of ulcers and bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract, the use of low doses of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), anticoagulants. On the other hand, the possible negative effect of NSAIDs on the cardiovascular system is class-specific, so it is also necessary to take into account risk factors for this type of complications: the presence of heart failure, arterial hypertension [22]. The physician must assess the severity of the risk and the combination of various risk factors in a particular patient [23]. Use of proton pump inhibitors with NSAIDs may enhance upper GI protection. If there is a risk of cardiovascular complications, combination with low doses of ASA and other antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants is possible, but the balance between harm and benefit must be assessed individually. Monitoring blood pressure may be important when selecting a NSAID therapy regimen.

GK

GCs may be prescribed as part of the initial treatment strategy for patients with RA to control disease activity. The main methods of using GCs in RA are low doses orally (prednisolone 5–10 mg/day or methylprednisolone 4–8 mg/day) and intra-articular administration of long-acting drugs (betamethasone, methylprednisolone and triamcinolone). Higher doses of oral GCs or GC pulse therapy are used very rarely - in severe systemic manifestations of the disease. There is evidence that the combination of a low dose of oral GC with DMARDs increases the clinical effectiveness of treatment and helps inhibit joint destruction [24]. Due to the fairly high likelihood of treatment complications (infections, osteoporosis, fluid retention, decreased glucose tolerance, etc.), it is recommended to use the lowest possible dosages of GCs and reduce the duration of their use until the effect of DMARDs develops (the so-called “bridge therapy”). , careful monitoring of the patient’s condition, prophylactic administration of antiosteoporetic drugs.

Synthetic DMARDs

The use of s-DMARDs is still the basis and mandatory component of the treatment of RA. Traditional DMARDs have different chemical structures and mechanisms of action. They can be conditionally divided into drugs with a predominantly (used for the treatment of RA) immunomodulatory effect - MTX, LEF, sulfasalazine (SSZ), hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), cyclosporine A, azathioprine and predominantly cytotoxic drugs (cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, etc.), which either have practically fallen out of use, or are prescribed very rarely in special cases (severe rheumatoid vasculitis, Sjögren's syndrome, etc.). The previously widely known drugs gold and penicillamine are now practically not used due to their unfavorable safety profile.

MTX is preferable to other s-DMARDs in terms of efficacy and safety and should be the first drug used in patients with RA in the absence of contraindications. No other sDMARD or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) inhibitor alone is superior in clinical efficacy to MTX. For all GEBDs, it has been shown that their combination with MTX is superior in effectiveness to monotherapy [25]. MTX is also a mandatory component [24, 26] of recommended s-DMARD combinations (MTX + CVD, MTX + HCQ, MTX + CVD + HCQ, MTX + cyclosporine A). MT should be initiated orally or parenterally (doses may vary, but a starting dose of 10–15 mg/week is generally recommended) and titrated to a maximum dose of 25–30 mg/week. The optimal dose escalation schedule depends on the clinical picture and tolerability of MTX in the individual patient. The safety profile of low-dose MTX used to treat RA when administered weekly has been studied for over 25 years, with very few clinically significant side effects [27]. In patients with an inadequate response or intolerance to oral MTX, parenteral administration of the drug should be discussed. In this case, the best results can be obtained by using the subcutaneous form of MT [28], which provides the best pharmacokinetic profile.

GIBP

To date, 8 biologically active drugs have been approved for the treatment of RA in the Russian Federation. They belong to different classes depending on the mechanism of action, chemical structure and foreign (mouse) protein content (Table 3). Structural features are most important for the group of TNF-α inhibitors, among which the phenomenon of immunogenicity (production of antibodies to the drug) is most often observed, leading to loss of effect. Immunogenicity is most pronounced in TNF-α inhibitors, which are classified as monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) and contain murine protein.

TNF-α inhibitor therapy is recommended for the treatment of patients with an inadequate response to traditional DMARDs. Inadequate response is defined as persistence of moderate or high disease activity despite the use of MTX and/or other s-DMARDs in monotherapy or combination therapy for 3–6 months. provided that it is used in recommended doses. It has been shown that biologically active drugs with other mechanisms of action can be successfully used as first-line drugs for biological therapy [15].

Switching to a DMARD after failure of MTX has been questioned in several recent studies using “triple therapy” s-DMARDs (MTX + CVD + HCQ). O'Dell et al. in the TEAR study [29] showed that in patients who did not sufficiently respond to MTX treatment, “triple therapy” was not inferior in clinical response to the combination of MTX and etanercept. The same authors in the RACAT study [30] demonstrated the possibility of a successful transition not only from “triple therapy” to the combination of MTX + TNF-α inhibitor, but also vice versa, and the results were quite comparable.

Targeted DMARDs

This new group of drugs for the treatment of immunoinflammatory diseases (also called “small molecules”) includes the only drug registered in Russia (as well as in the USA, Japan, Switzerland and a number of other countries) tofacitinib (TOFA). It is a low-molecular-weight inhibitor of the intracellular enzyme Janus kinase, which is part of the intracellular Jak-STAT signaling system, consisting of Jak kinases and the signal transducer protein and activator of transcription STAT (Janus Kinases - Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription). The biological role of this system is the intracellular transmission of signals from immune system mediators (for example, cytokines). In this regard, a number of pharmacodynamic effects of TOFA are explained by the blockade of the biological action of interleukin-6 (IL-6), and the therapeutic characteristics of the drug overlap to a certain extent with those of tocilizumab [31]. TOFA studies in phase 3 clinical trials for RA were conducted on a large clinical material within the framework of 6 controlled studies of the ORAL series, which studied the main clinical situations in which the use of a new anti-inflammatory/immunomodulatory drug may be required. A total of 4267 patients took part in these studies. All TOFA studies achieved their primary endpoints and demonstrated a good clinical effect of the drug combined with satisfactory safety [32]. The drug is promising, especially considering the possibility of oral administration. At the same time, there is concern regarding some aspects of its safety, and the experience of practical use of this new drug is insufficient to draw specific conclusions about its real place in modern RA therapy.

EULAR clinical guidelines for the treatment of RA

In modern conditions, when there are a significant number of therapeutic options for the treatment of RA, clinical recommendations are of particular importance. The most authoritative are the EULAR recommendations, which are international in nature and highly scientifically sound. The latest version of these recommendations for drug treatment of RA was adopted in 2013 [15] and immediately began to be actively discussed in our country [25, 33]. A summary of the EULAR 2013 recommendations is presented in Table 4.

The recommendations begin with basic principles postulating that:

A. Therapy for patients with RA should be aimed at the best treatment results as a joint decision between the patient and the rheumatologist.

B. Rheumatologists are specialists who should primarily manage patients with RA.

C. Treatment of RA involves high individual, social and medical costs, which must be taken into account by the treating rheumatologist when managing the patient.

These principles are undoubtedly very general, but it is necessary to note the high importance of the work of a rheumatologist and his contacts with the patient.

Specific recommendations emphasize the importance of MTX as an “anchor” drug in the treatment of RA as monotherapy and as a component of combination treatment regimens. It should be noted that GEBD therapy is considered only in combination with MTX. Monotherapy with GEBD is not discussed, since it is well proven that treatment of GEBD in the vast majority of cases is justified in combination with s-DMARDs. On the other hand, the new version of the recommendations takes a “democratic” approach to the choice of the first biologic drug, allowing, in addition to TNF-α inhibitors, the use of drugs with other mechanisms of action. Overall, the new EULAR guidelines (2013) are an important contribution to scientific rheumatology and practical healthcare. Their implementation will undoubtedly help improve the quality of medical care for patients with RA. In addition, these recommendations can become a good basis for the development of a new edition of Russian national recommendations for the management of patients with RA.

Literature

- Balabanova R.M., Erdes S.F. Rheumatic diseases in the adult population in the federal districts of Russia // Scientific and practical rheumatology. 2014. No. 52. pp. 5–7.

- Galushko E.A., Erdes Sh.F., Bazorkina D.I. et al. Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in Russia (according to an epidemiological study) // Therapeutic archive. 2010. No. 5. pp. 9–14.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D., Machold KP Therapeutic strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis // Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2005. Vol. 19. R. 163–77.

- Karateev D.E., Olyunin Yu.A., Luchikhina E.L. New classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis ACR/EULAR 2010 – a step forward towards early diagnosis // Scientific and practical rheumatology. 2011. No. 49. pp. 10–15.

- Aletaha D., Neogi T., Silman AJ et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative // Ann Rheum Dis. 2010. Vol. 69. R. 1580–1588.

- Luchikhina E., Karateev D., Novikov A. et al. Performance and predictive value of ACR/EULAR2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria in different groups of patients with early arthritis // Ann Rheum Dis. 2011. Vol. 70. Suppl. 3. R. 285 (THU0324).

- Karateev D.E., Luchikhina E.L. Early rheumatoid arthritis / In the book: Genetic engineering biological drugs in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis / ed. E.L. Nasonova. M.: IMA-Press, 2013. pp. 65–77. 8. Landewé R. Predictive markers in rapidly progressing rheumatoid arthritis // J Rheumatol Suppl. 2007. Vol. 80. R. 8–15.

- Emery P., McInnes IB, van Vollenhoven R., Kraan MC Clinical identification and treatment of a rapidly progressing disease state in patients with rheumatoid arthritis // Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008. Vol. 47. R. 392–398.

- Brown AK, Conaghan PG, Karim Z. et al. An explanation for the apparent dissociation between clinical remission and continued structural deterioration in rheumatoid arthritis // Arthritis Rheum. 2008. Vol. 58. R. 2958–2967.

- Vastesaeger N., Xu S., Aletaha D., St Clair E., Smolen J. A pilot risk model for the prediction of rapid radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritis // Rheumatology. 2009. Vol. 48. R. 1114–1121.

- Demidova N.V. The relationship of immunogenetic and immunological markers and their influence on disease activity and radiological progression in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis // Scientific and practical rheumatology. 2009. No. 3. pp. 12–17.

- Nam J., Villeneuve E., Emery P. The role of biomarkers in the management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis // Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009. Vol. 11. R. 371–377.

- Karateev D.E. Modern view on the problem of rapidly progressive rheumatoid arthritis // Modern rheumatology. 2010. No. 2. P. 37–42.

- Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update // Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Mar. Vol. 73(3). R. 492–509. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573.

- Smolen J., Aletaha D., Bijlsma J. et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force // Ann Rheum Dis. 2010. Vol. 69. R. 631–637.

- Karateev D.E., Olyunin Yu.A. On the classification of rheumatoid arthritis // Scientific and practical rheumatology. 2008. No. 1. P. 5–17.

- Nasonov E.L., Karateev D.E., Balabanova R.M. Rheumatoid arthritis / In kN.: Rheumatology. National leadership / ed. E.L. Nasonova, V.A. Nasonova. M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2008. pp. 290–331.

- Aletaha D., Smolen J. The Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) and the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI): a review of their usefulness and validity in rheumatoid arthritis // Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005. Vol. 23 (5. Suppl 39). R. 100–108.

- Felson D., Smolen J., Wells G. et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis in clinical trials // Arthr Rheum. 2011. Vol. 63. R. 573–586.

- Smolen JS, van der Heijde D., Machold KP, Aletaha D., Landewé R. Proposal for a new nomenclature of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs // Ann Rheum Dis. 2014. Vol. 73(1). R. 3–5. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204317.

- Karateev A.E., Yakhno N.N., Lazebnik L.B. etc. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clinical recommendations. M.: IMA-press, 2009. 167 p.

- Karateev A.E. The use of NSAIDs: a schematic approach // Russian Medical Journal. 2011. No. 25. pp. 1558–1559.

- Gaujoux-Viala C., Nam J., Ramiro S. et al. Efficacy of conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, glucocorticoids and tofacitinib: a systematic literature review informing the 2013 update of the EULAR recommendations for management of rheumatoid arthritis // Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Mar. Vol. 73(3). R. 510–515. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204588.

- Nasonov E.L., Karateev D.E., Chichasova N.V. New recommendations for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (EULAR 2013): the place of methotrexate // Scientific and practical rheumatology. 2014. No. 52. pp. 8–26.

- Kumar P., Banik S. Pharmacotherapy Options in Rheumatoid Arthritis // Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2013. Vol. 6. R. 35–43.

- Kaltsonoudis E., Papagoras C., Drosos A. Current and future role of methotrexate in the therapeutic armamentarium for rheumatoid arthritis // Int J Clin Rheumatol. 2012. Vol. 7. R. 179–189.

- Braun J. Methotrexate: Optimizing the Efficacy in Rheumatoid Arthritis // Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2011. Vol. 3 (3). R. 151–158. doi: 10.1177/1759720X11408635.

- O'Dell JR, Curtis JR, Mikuls TR et al. Validation of the methotrexate-first strategy in patients with early, poor-prognosis rheumatoid arthritis: results from a two-year randomized, double-blind trial // Arthritis Rheum. 2013. Vol. 65. R. 1985–1694. doi: 10.1002/art.38012.

- O'Dell JR, Mikuls TR, Taylor TH et al. Therapies for active rheumatoid arthritis after methotrexate failure // N Engl J Med. 2013. Vol. 369. R. 307–318.

- Karateev D.E. New direction in pathogenetic therapy of rheumatoid arthritis: the first Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib // Modern Rheumatology. 2014. No. 1. P. 39–45.

- Feist E., Burmester G. Small molecules targeting JAKs—a new approach in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis // Rheumatology. 2013. Vol. 52. R. 1352–1357.

- Nasonov E.L., Karateev D.E., Chichasova N.V. EULAR recommendations for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis - 2013: general characteristics and controversial issues // Scientific and practical rheumatology. 2013. No. 51. pp. 609–623.

What treatments are there for rheumatoid arthritis?

Treatment methods for RA have changed significantly in recent years due to the emergence of new effective drugs. Currently, the emphasis is on using a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) as early as possible. Increasingly, this allows one to achieve remission (that is, a state in which there are no symptoms of the disease and no signs of disease activity in laboratory and imaging tests) or low disease activity. Unfortunately, the onset of RA is often subtle, and it often takes several months before appropriate treatment begins - so don't delay visiting your doctor if you experience symptoms of arthritis!

Effective treatment of RA means the disappearance of symptoms of the disease, a good quality of life and maintaining physical fitness. In addition to the basic pharmacological treatment of this disease, early initiation of rehabilitation and, in some cases, surgical treatment is important. The rheumatologist decides which specific medications to use, taking into account the severity of the disease, its activity (most often using the DAS-28 index), prognostic indicators and contraindications to the use of certain medications (for example, liver disease, kidney disease, tuberculosis) . It is important to develop an effective action plan with your doctor - this includes regular visits and laboratory tests that evaluate the effectiveness and possible side effects of the drugs used.

Pharmacological treatment of rheumatoid arthritis

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) play a major role in the treatment of RA because they not only relieve symptoms, but primarily inhibit joint destruction, allowing physical function and normal functioning in daily life to be maintained. They should be prescribed immediately, immediately after diagnosis, to prevent irreversible changes in the joints. These drugs, however, do not provide complete recovery; after stopping their use, the disease usually recurs. There are “non-biological (synthetic)” and “biological” DMARDs.

Non-biological DMARDs include:

- methotrexate

- leflunomide

- sulfasalazine

- gold salts

- chloroquine

The initial effect of these drugs appears after some time, usually after 1-2 months (full - after 3-6 months). Methotrexate is the first-line drug for RA, it is very effective and is usually well tolerated (many side effects are temporary).

Over the past few years, so-called drugs have been increasingly used in the treatment of RA. biological drugs obtained using genetic engineering methods that are directed against factors involved in the inflammatory process. There are several types of biologics, depending on their target site of action (including TNF, IL-1, IL-6, T or B lymphocytes).

The most commonly used treatments for RA are:

- adalimumab

- etanercept

- infliximab

- certolizumab

- golimumab

- abatacept

- tocilizumab

- rituximab

The effects of these drugs are noticeable a little faster, usually within 2-6 weeks. They can be used alone or in combination with synthetic drugs (most often methotrexate). Biologics are intended for patients who have failed to achieve adequate disease control despite maximum tolerated doses of synthetic drugs, and less commonly as initial treatment for people with high disease activity and poor prognostic factors.

Glucocorticosteroids quickly relieve the symptoms of arthritis and slow down the process of joint destruction, so they are often used at the onset of the disease (before the basic DMARD begins to act) and during its exacerbations. Due to the many side effects, it is necessary to try to reduce the dose of the glucocorticosteroid as soon as possible and use it for a short period. Corticosteroids can also be injected directly into the affected joint (see: Prednisolone, Methylprednisolone).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs relieve the symptoms of arthritis, but do not suppress the progression of the disease, so they are used only as aids in the fight against pain and stiffness in the joints. They have many side effects, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, kidney damage, and an increased risk of heart disease. Never take more than one drug from this group and do not exceed the recommended dosage See some drugs from this group: Diclofenac, Ibuprofen, Ketoprofen, Naproxen, Nimesulide

Painkillers such as paracetamol and opioids are used if, despite comprehensive basic therapy, pain symptoms persist.

Non-pharmacological treatment of rheumatoid arthritis

In all patients, in addition to the use of medications, it is very important:

- psychological support - remember that an illness, which is often associated with pain and disability, can also cause frustration, a feeling of dependence on others, and even depression, so do not hesitate to seek psychological support from loved ones and in specialized centers; Some methods (eg biofeedback and behavior therapy) are very effective in controlling symptoms and improving self-esteem

- rest - fatigue is a common symptom of RA, especially in its active period; allow yourself to rest - a short nap during the day will help you replenish your energy and bring relief to sore joints

- exercise - patients with RA often refuse any physical activity, which leads to decreased joint mobility, contractures and muscle weakness; regular physical activity prevents some unfavorable changes in the joints, and even eliminates them; Exercises that increase range of motion and strengthen muscles (help maintain joint mobility and stability) and exercises that improve general endurance (eg, walking, swimming, cycling) are recommended. the exercise program should be developed by a physiotherapist and should be adapted to each patient individually, depending on the severity of the disease, the condition of the person and concomitant diseases

Important

Exercise should be avoided if symptoms of the disease worsen; remember that the sooner you begin targeted rehabilitation, the easier it will be to prevent deformation and immobility of the joints.

- physiotherapy - various methods such as cryotherapy, ultrasound, massage and balneotherapy help reduce pain and inflammation of the joints, as well as relax the muscular system; their use requires a careful assessment of health status and consideration of possible contraindications.

- orthopedic devices help reduce the load on sore joints and cope with disability - these are canes, crutches, walkers, wheelchairs to facilitate movement, stabilizers for the arms, knees and ankles (so-called orthoses), which help maintain the correct position of the joints, orthopedic insoles for shoes, improving the structure of the foot and unloading the supporting joints when walking

- adaptation of the environment to the disability , e.g. specially adapted kitchen equipment, furniture, handles to help with lifting, adapted car - will help to perform everyday activities

- appropriate diet - we are talking about maintaining normal body weight; Avoid both overweight and obesity (which increase stress on joints and accelerate the development of atherosclerosis) and malnutrition (which weakens the body and leads to muscle atrophy); It is also important to provide the bones with the necessary amount of calcium and vitamin D, since RA significantly accelerates the development of osteoporosis

- stopping smoking , which increases the risk of developing and severe disease.

Local treatment of rheumatoid arthritis

Local treatment of rheumatoid arthritis concerns the affected joint directly.

Performed:

- puncture of the joint to decompress it from accumulated inflammatory fluid and administer anti-inflammatory drugs (corticosteroids) internally

- procedures to remove altered synovial membrane (so-called synovectomy) - there are different ways to perform them: surgical, chemical (by introducing a substance that destroys the synovial membrane) or using a radioisotope

- various types of correction and reconstructive procedures, the main goal of which is to improve the structure and functioning of deformed joints

- endoprosthetics, i.e. replacing a damaged joint with an artificial prosthesis

- arthrodesis based on complete stabilization of the joint, thereby eliminating pain

- decompression of carpal tunnel syndrome, which often accompanies RA.

Severe variant of rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is considered one of the most severe chronic human diseases. The disease is characterized by severe inflammation with proliferation of the synovial membrane of the joints, damage to internal organs and systems, long-term persistence of inflammatory activity and gradual destruction of joint structures and periarticular tissues. Until recently, during the first 5 years of the disease, more than 40% of RA patients became disabled [1]. In addition, many authors report that RA reduces the life expectancy of patients by an average of 10 years [2, 3].

The course of RA is highly variable. This is due to many reasons. The patient may be resistant to treatment, or the therapy may not be tolerated. Delay in prescribing therapy with disease-modifying anti-inflammatory drugs (DMARDs) also worsens the prognosis in RA. In addition, it is known that inflammation in the synovium can begin to develop long before the first clinical symptoms of the disease appear. It is known that serological tests such as rheumatoid factor (RF) and/or antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptide (ACCP) are detected in the blood of patients with RA several years before the onset of arthritis (up to 10 years) [4] (Fig. 1).

A morphological study of the synovial membrane obtained from patients in the first months of the onset of arthritis showed that not all patients show signs of acute rheumatoid inflammation; in some patients, clear signs of chronic synovitis are noted already in the first biopsy [5]. It was in these patients that a more torpid variant of RA was observed with a poor response to DMARD therapy. The severity of the condition of a patient with RA at each stage depends on the level of inflammatory activity, which determines the severity of joint pain, stiffness, and functional disorders. With adequate therapy and suppression of activity before the development of irreversible anatomical changes in the joints (destruction, deformation), the function of the joints is restored (

). A severe variant of the course of the disease is formed due to inadequate or ineffective therapy and is determined by the degree of persistent loss of the patient’s functional ability not only for professional work, but also for self-care. Therefore, the earliest possible start of anti-inflammatory therapy is of fundamental importance in RA.

In the last decade, criteria for early RA [6] have been introduced into rheumatologist practice for timely referral of the patient to a rheumatologist and early initiation of therapy. It is ideal to start DMARD therapy immediately after the first symptoms of inflammation in the synovium appear: morning stiffness, joint pain and swelling. In practice, a patient with the onset of RA sometimes goes through a long path of consultations and diagnostic measures before meeting with a rheumatologist. In addition, the onset of the disease may be clinically mild and the symptoms of the disease increase slowly, which makes it difficult to establish a diagnosis of RA. According to foreign authors [7] and our data [8], with the acute onset of RA, the long-term outcome of the disease is better than with a gradual onset of the disease. Probably, the acute onset of the disease forces the patient to seek medical help more quickly and allows the doctor to quickly determine the diagnosis and begin therapy. Our data indicate a better outcome of RA, assessed after 15 years of illness in terms of the degree of preservation of musculoskeletal function, severity of destruction in the joints, the frequency of long-term remissions and patient survival, when DMARDs are prescribed in the first 6 months from the onset of arthritis symptoms [9]. Delay in initiation of DMARDs results in poorer response to these drugs, as has been shown in controlled trials [10]. Methotrexate and leflunomide are considered first-line drugs. Both drugs are capable of suppressing the activity and progression of RA in most patients, especially when prescribed in the first months of the disease. But starting therapy in a very early period of the disease (1–2 months) does not in all cases achieve a pronounced effect (clinical remission or maintenance of subclinical RA activity). First, the patient may not respond to the basic drug; secondly, in many patients, the effectiveness of DMARDs decreases after 1–2 years of therapy; in some patients, sequential changes in basic drugs occur due to symptoms of intolerance. When sequentially prescribed DMARDs are ineffective and/or intolerable, a severe variant of RA develops. The most significant parameters for determining the severity of RA are the severity of destructive changes in the joints and the degree of persistent loss of functional ability of the joints, up to the loss of the patient’s ability to self-care.

A large number of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) were devoted to identifying the most effective therapeutic strategies in the treatment of patients with RA: treatment results were compared with sequential monotherapy of DMARDs, with their combination both at the onset of the disease (step-down strategy), and with the addition of a second or third drug at ineffectiveness of the first remedy (step-up strategy).

A comparative assessment of the effectiveness of monotherapy with methotrexate, sulfasalazine, antimalarials, cyclosporine A, leflunomide and their combinations [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18] did not show a clear advantage of combination therapy of DMARDs over their use as monotherapy . A number of studies have shown that after 6, 12 and 24 months, the clinical effect was more pronounced when using a combination of DMARDs (either with a step-up or step-down strategy) [14, 16, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23], according to other authors [24, 25], there were no significant differences in the effect of monotherapy or combination of DMARDs on activity indicators. When the study period was extended (up to 5 years), no advantage was noted in the effect of the combination of DMARDs over monotherapy on the activity of RA [11, 23, 24]. Evaluation of radiographic changes in joints after 1–2 years did not show any advantage of combination treatment in the MASCOT study [16], and the combination of cyclosporine A and methotrexate in two studies after 6 [26] and 12 [27] months suppressed the progression of destruction to a greater extent than monotherapy with methotrexate. In the FIN-RACo study, the change in Larsen score was significantly less when using a combination of DMARDs after 2 years [14], but after 5 years there were no significant differences between combination therapy and monotherapy [15].

Very interesting are the data obtained as a result of the TICORA study [12, 28], which compared the results of 18-month treatment of two groups of RA patients: in group 1, treatment was carried out with strict monthly monitoring of changes in RA activity according to DAS (tight-control) and in In accordance with the dynamics of DAS, therapy was adjusted (“intensive” group). In group 2, treatment was carried out in a “routine manner” without such strict control. By the end of the study, remission was achieved in 65% of patients in group 1 and only in 16% of patients in group 2. The increase in the number of erosions was less in group 1. Controlled treatment (“intensive” group) was accompanied by more frequent correction of therapeutic tactics (use of a combination of DMARDs, escalation of their dose, use of intra-articular injections of glucocorticoids). The authors, when analyzing these results, concluded that control of treatment provides the best results, regardless of the choice of DMARDs. The same conclusion was made by Albers JM et al. [29] when evaluating the results of four different DMARD regimens: strict control over the success of treatment ensures similar results of treatment with different DMARDs. When evaluating methotrexate treatment in patients with early RA (disease duration < 1 year) in the CAMERA study [17, 18], it was also concluded that strict monthly monitoring of the dynamics of disease activity (tight-control) and timely correction of therapy allow achieving a significantly better result over the period 2-year follow-up. Thus, in the intensive control group (n = 76), the remission rate was 50%, and in the routine treatment (n = 55) - 37% (p = 0.03) [18]. These data also confirm our opinion, based on the results of a longer open study of the effectiveness of basic therapy in 240 patients: improvement in the functional, radiological and life outcomes of RA depends not only on the timing of the start of treatment, but also on the degree of continuous monitoring of the progress of treatment [9] .

Even with a competent approach to treating patients with RA with classical DMARDs (early initiation of therapy and constant monitoring of the degree of suppression of disease activity and progression), a severe version of the disease still develops. According to our data and literature data, in 15–25% of patients, sequentially prescribed DMARDs do not lead to the development of a pronounced effect (good effect according to EULAR criteria or more than 50% improvement according to ACR criteria) or lead to the development of adverse reactions and the need for their withdrawal. The creation of genetically engineered biological drugs (GEBPs) has made it possible to significantly optimize the treatment of patients with RA.

Currently, two tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) blockers are registered in the Russian Federation - infliximab (Remicade) and adalimumab (Humira) and the drug rituximab (MabThera), which binds CD20 B cells. TNF-alpha inhibitors have demonstrated advantages over methotrexate monotherapy in both early [30, 31] and advanced RA [32, 33] (

,

). Remission (according to EULAR criteria) in early RA according to the ASPIRE study developed in 15% of patients receiving methotrexate and in 21.2% of patients receiving a combination of infliximab and methotrexate (p = 0.065), and according to the PREMIER study in 21% of patients with methotrexate therapy and in 43% with a combination of adalimumab and methotrexate (p < 0.001). An even greater difference in the effectiveness of classical DMARDs and GEBDs is noticeable in advanced RA, when achieving 70% improvement according to ACR criteria is either not observed when prescribing methotrexate (ATTRACT study) or is observed in a small number of patients (4.8%) (according to the ARMADA study ). When used in combination with infliximab [32] or adalimumab [33], a 70% improvement was observed in 53% and 67%, respectively. Both TNF-alpha inhibitors begin to act in the first weeks of treatment, have a pronounced anti-inflammatory effect and are able to suppress destruction in the joints (

, 6).

Treatment with rituximab is carried out when TNF-alpha inhibitors are ineffective, although the drug can be used as a first biological agent. Repeated courses of rituximab are no less effective than the first. At the same time, no increase in the number of infusion or other adverse reactions was registered.

According to the pan-European updated consensus on biologics in the treatment of rheumatic diseases [34] (level of evidence in parentheses):

- there is no evidence that any TNF blocker is more effective than other drugs in this group and should be used first (A, B);

- switching from one TNF blocker to another is possible, but no double-blind studies have been conducted (B, D);

- there may be a loss of clinical effect, and an insufficient response to one TNF blocker does not exclude the development of a good response to another (B, D);

- with primary failure of one drug, a good response to another is less likely (B);

- if you are intolerant to one of the TNF blockers, the risk of intolerance to the second increases (B, D);

- the optimal treatment regimen for patients who do not respond to TNF blockers has not yet been developed (A);

- TNF blockers slow or stop radiographic progression in RA, even in some patients who do not respond to treatment according to clinical parameters (A).

Taking into account the high cost of treatment with biologically active drugs, the issue of selecting patients for biological therapy seems important. As was shown in the BEST study [13], if two sequentially prescribed classical DMARDs are ineffective, further use of other DMARDs does not lead to the development of an effect. Therefore, in many European countries, one of the criteria for selecting patients to prescribe a DMARD is the ineffectiveness of two DMARDs. However, there are other risk factors for rapid progression of the disease in the early stages, among which the following are discussed:

- onset of RA at a young age;

- the presence of more than four swollen joints;

- DAS score ≥ 4.21;

- the presence of erosions on radiographs or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the first months of the disease;

- increased C-reactive protein (CRP) more than 0.6 mg/dl;

- increase in ESR more than 28 mm/h.

It has been shown that when using methotrexate in patients with high levels of both ESR and CRP, a very high risk of progression remains, with an increase in one of these two laboratory parameters, a high risk of progression remains, and with a decrease in ESR and CRP to normal values, an average risk still remains progression. And only the addition of a biological agent can reduce the risk of progression to low [35]. However, classical DMARDs are capable of having a pronounced effect at the onset of RA and suppressing the radiological progression of destruction in a significant number of patients. In our practice, patients with an established diagnosis of RA are immediately prescribed methotrexate or leflunomide; if there are contraindications to them, the choice of the basic drug is discussed individually. The patient is then monitored monthly until a pronounced effect develops. When using methotrexate or leflunomide, the effect begins to appear after 4–6 weeks; if the effect does not begin to appear within this period, then the dose of methotrexate is increased, and the issue of continuing treatment with leflunomide is decided individually. During the first 3–4 months of treatment, it should be established whether the effect develops and what its severity is. This control over the degree of activity suppression leads to rapid adjustment of therapy, if required. With the development of 50% (or more) improvement, further during the first year of therapy, it is assessed whether there is suppression of the progression of erosive arthritis. Insufficient anti-inflammatory effect or the appearance of new erosions in the joints of the hands and feet, the development of destruction of large joints, and the persistence of extra-articular manifestations should lead to a change in therapy: a change in DMARDs, a combination of DMARDs, or their combination with a biologically active drug. Involvement in symptomatic therapy, the desire to suppress activity with frequent intra-articular or intravenous administration of glucocorticoids in the absence of a sufficient and stable effect of DMARDs do not prevent the development of severe RA. These measures can only be an addition to DMARD treatment, but not a replacement for it.

Thus, to prevent loss of function in patients with RA, i.e., to prevent the formation of a severe variant of the disease, the doctor must provide the following:

- early administration of DMARDs to all patients with RA;

- educate the patient explaining the goals of therapy, the need for long-term (many months and many years) treatment, the need to monitor drug tolerability;

- conducting constant monitoring of the degree of suppression of activity and progression of the disease with an objective assessment of the quantitative severity of the articular syndrome and destructive changes in the joints, and the tolerability of therapy;

- if two sequentially prescribed DMARDs are ineffective, raise the question of the need to prescribe a GIBD.

To objectively monitor the activity of RA at each stage of treatment, the doctor must record the number of painful and swollen joints, the severity of pain as assessed by the patient, the general condition as assessed by the patient and the doctor using a visual analogue scale, as well as laboratory parameters (ESR and CRP). The dynamics of these indicators will be an objective assessment of the success (or failure) of the therapy and will contribute to rapid correction of treatment.

Literature

- Balabanova R. M. Guidelines for internal diseases, 1997, chapter 9, pp. 257–294.

- Goodson N., Symmons D. Rheumatoid arthritis in women: still associated with increased mortality. Ann. Rheum. Dis., 2002,61:955–956.

- Riise T, Jacobsen BK, Gran JT et al. Total mortality is increased in rheumatoid arthritis. A 17-year prospective study // Clin. Rheum., 2002, 20: 123–127.

- Nielen MM, van Schaadenburg D., Reesnik HW et al. Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: A study of serial measurement in blood donors // Arthr. Rheum., 2004, v. 50: 380–386.

- Shekhter A. B., Krel A. A., Chichasova N. V. Clinical and morphological comparisons in various types of rheumatoid arthritis (according to puncture biopsies of the synovial membrane) // Therapeutic archive, 1985, No. 8, 90–100.

- Emery P., Breedveld F., Dougados M. et al. Early referral recommendation for newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis: evidence based development of a clinical guide // Ann. Rheum. Dis., 2002, v. 61:290–297.

- Zatarain E., Strand V. Monitoring disease stativity of rheumatoid arthritis in clinical practice: contributions from clinical trials // Nature Clinical Practice Rheumatology, 2006, v. 2, No. 11: 611–618.

- Chichasova N.V. Treatment of various variants of the course of rheumatoid arthritis // Mosk. honey. magazine, 1997, no. 1, 21–26.

- Kanevskaya MZ, Chichasova NV Treatment of early rheumatoid arthritis: influence on parameters of activity and progression in long-term prospective study // Ann. Rheum. Dis., vol. 672, Suppl. 1, 2003, p. 179 (Annual European Congress of Rheumatology, EULAR 2003, Abstracts, Lisbon, 18–21 June 2003).

- Han C., Smolen JS, Kavanaugh A. et al. Impact of disease duration and physical function on employment in RA and PsA patients // Arthr. Rheum., 2006, v. 54, Suppl. P. S54.

- Maillefert JF, Combe B, Goupille P et al. Long-term structural effects of combination therapy in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: five-year follow up of a prospective double blind controlled study // Ann. Rheum. Dis., 2003, v. 62:764–766.

- Grigor C., Capell H., Stirling A. et al. Effect of treatment strategy of tight control of rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomized controlled trial // Lancet, 2004, v. 364:263–269.

- Goecor-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeST study): a randomized, controlled trial // Arthr. Rheum., 2005, v. 52:3381–3390.

- Mottonen T., Hannonen P., Leirisalo-Repo M. et al. Comparison of combination therapy with single drug in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. FIN-RACo Group // Lancet, 1999, v. 353:1568–1573.

- Korpela M., Laansonen L., Hannonen P. et al. Retardation of joint damage in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis by initial aggressive treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: five-year experience from FIN-RACo study // Arthr. Rheum., 2004, v. 50:2072–2081.

- Capell H., Madhok R., Porter D. et al. Combination therapy with sulphasalazine and methotrexate is more effective than either drug alone in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients with a suboptimal response to sulphasalazine: result from the double-blind placebo controlled MASCOT study // Ann. Rheum. Dis., 2007, v. 66:235–241.

- Bijlsma JW, Weinblatt ME Optimal use of the methotrexate: the advantages of tight control // Ann. Rheum. Dis., 2007, v. 66:1409–1410.

- Verstappen SMM, Jacobs JW, van der Veen MJ et al. Intensive treatment with methotrexate in early rheumatoid arthritis: aiming for remission. Computer Assisted Management in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (CAMERA, an open-label strategy trial) // Ann. Rheum. Dis., 2007, v. 66:1443–1449.

- Haagsma CJ, van Riel PL, de Jong AJ, van de Putte LB Combination of sulphasalazine and methotrexate versus methotrexate alone: a randomized open clinical trial in rheumatoid arthrits patients resistant to suylphasalazine therapy // Dr. J. Rheum., 1994, v. 33:1049–1055.

- Dougados M., Combe B., Cantagrel A. et al. Combination therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled double-blind 52 week clinical trial of sulphasalazine and methotrexate with the single components // Ann. Rheum. Dos., 1999, v. 58: 220–225.

- Stein M. et al. Combination treatment of severe rheumatoid arthritis with cyclosporine and methotrexate for forty-eight weeks. An open-label extension study // Arthr. Rheum., 1997, v. 40: 1843–1851.

- Kremer J. et al. Concomitant leflunomide therapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite stable doses of methotrexate. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial // Ann. Int. Med., 2003, v. 137:726–733.

- Kremer J. et al. Combination leflunomide and methotrexate therapy for patients with active rheumatoid arthritis failing methotrexate therapy: open label extension of a randomized, double-blind placebo controlled trial // J. Rheum., 2004, v. 31: 1521–1531.

- Haagsma CJ, van Riel PL, de Jong AJ, van de Putte LB Combination of sulphasalazine and methotrexate versus the single components in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled, double-blind, 52 week clinical trial // Br. J. Rheum., 1997, v. 36:1082–1088.

- Hider SL, Silman AJ, Bunn D. et al. Comparing the long term clinical outcome between methotrexate and sulphasalazine prescribed as the first disease modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis // Ann. Rheum. Dis., published online March 15, 2006.

- Garards A. et al. Cyclosporine A monotherapy versus cyclosporine A and methotrexate combination therapy in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: a double blind randomized placebo controlled trial // Ann. Rheum. Dis., 2003, v. 62:291–296.

- Marchesoni A. et al. Radiographic progression in early rheumatoid arthritis: a 12-month randomized controlled study comparing the combination of cyclosporine A and methotrexate with methotrexate alone // Rheum., 2003, v. 42:1545–1549.

- Porter D. Targeting persistent disease activity in early RA: a commentary on the TICORA trial // Int. J Adv. Rheum., 005, v. 3:2–6.

- Albers JM, Paimela L., Kurki P. et al. Treatment strategy, disease activity, and outcome in four cohort of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis // Ann. Rheum. Dis., 2001, v. 60, 453–458.

- St. Clair EW, van der Heijde DM, Smolen JS et al. Combination of infliximab and methotrexate therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized, controlled trial // Arthritis Rheum 2004, 50: 3432–3442.

- Breedveld FC, Weissman MH, Kavanaugh AF et al. The PREMIER study: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had or did not have previous methotrexate treatment // Arthritis Rheum, 2006, 54 : 26–37.

- Maini RN, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR et al. Sustained improvement over two years in physical function, structural damage, and signs and symptoms among patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab and methotrexate // Arthr. Rheum., 2004, v. 50: 1051–106.

- Weinblatt ME, Keystone EC, Furst DE et al. Adalimumab, a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor a monoclonal antibody for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis patients taking concomitant methotrexate: the ARMADA trial // Arthr. Rheum., 2003, v. 48: 35–45.

- Furst DE, Keystone EC, Kirkham B. et al. Update consensus of biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseasis, 2008 // Ann. Rheum. Dis., 2008, v. 67: iii2–iii25.

- Smolen J, Van der Heijde DM, StClair EW et al. Prediction of joint damage in patients with rearly rheumatoid arthritis treated with high-dose methotrexate with or without concomitant infliximab: Results from ASPIRE trial // Arthritis Rheum., 2006; v. 54: 702–710.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis in clinical care // Ann. Rheum. Dis., 2004, v. 63:226–232.

N.V. Chichasova , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor G.R. Imametdinova , Candidate of Medical Sciences E.V. Igolkina S.A. Vladimirov MMA named after. I. M. Sechenova , Moscow

Is a complete cure for rheumatoid arthritis possible?

Currently, the cure for RA, i.e. the absence of illness without the need to take medications is very rare. The disease usually recurs after stopping DMARDs. Available treatments are increasingly making it possible to achieve remission of the disease and function normally. Unfortunately, in some patients (about 10–20%), despite treatment, the disease progresses. Remission often occurs in women during pregnancy, but the disease usually worsens within 3 months after birth.

RA continues to be associated with frequent disability—it is estimated that after 5 years, about half of patients are unable to work, and after 10 years, almost all are. Affected individuals live several years shorter than the general population, mainly due to complications of atherosclerosis. It is likely that, thanks to earlier detection of RA and increasingly effective treatments, these statistics will improve in the future.

What should you do after finishing treatment for rheumatoid arthritis?

RA is a chronic disease that requires constant rheumatological monitoring. At the onset of the disease and during its exacerbations, frequent visits to the doctor (on average every 1-3 months) are mandatory to determine the appropriate dosage of medications and achieve remission of the disease. During the stable period, visits may be less frequent (usually every six months).

Disease activity and progression are assessed based on the severity of clinical symptoms (number of affected joints, pain severity score, quality of life scale) and the results of laboratory tests (ESR, CRP, complete blood count) and imaging (RH of the hands and feet). It is important to diagnose side effects of drugs, including assessment of kidney, liver and bone marrow function, and periodic examinations for the presence of concomitant diseases (ultrasound of the abdominal cavity, X-ray of the chest, mammography, gynecological control). Due to the accelerated development of atherosclerosis, an assessment of the risk of cardiovascular diseases and, if necessary, appropriate prevention and treatment are necessary.

You should also remember to treat osteoporosis appropriately early to reduce the risk of bone fracture. In addition to visiting a rheumatologist, the patient should participate in targeted rehabilitation sessions and perform recommended exercises at home.

Advice from a rheumatologist for patients with rheumatic diseases