Pain caused by degenerative processes in the joints causes a person considerable discomfort. One of the mandatory prescriptions of an orthopedic doctor is non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which sometimes the patient begins to take at his own discretion in large quantities. What do you need to remember so as not to further harm your health?

Uncontrolled use of NSAIDs is a direct path to exacerbation of gastrointestinal diseases

What are NSAIDs

The purpose of non-hormonal anti-inflammatory drugs is to reduce and eliminate inflammation in the joints. The absence of hormones makes the effect of the medications quite mild and eliminates serious side effects. However, this is only true if the treatment of arthrosis or osteoarthritis is carried out under the supervision of a specialist.

What is the principle of action of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs? How to take them correctly? Experienced doctor, chiropractor Anton Epifanov says:

Algorithms for safe therapy with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

In recent years, periodicals have increasingly published reports on complications of therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), primarily on the toxic effect of these drugs on the gastrointestinal tract. Considering the extreme demand for non-steroidal drugs in modern outpatient and hospital practice and the enormous volume of their prescription and over-the-counter supply, the problem of complications of NSAID therapy for the population as a whole is becoming very acute.

The problem of nonsteroidal gastropathy is traditionally located at the intersection of several medical specialties: on the one hand, neurologists, rheumatologists and therapists, who most often prescribe NSAIDs, on the other hand, gastroenterologists, who, by definition, must identify and treat patients with nonsteroidal gastropathy. But, unfortunately, surgeons most often have to deal with NSAID-induced damage to the digestive tract. This is due to the characteristic features of the clinical course of NSAID-induced gastropathy, primarily the paucity or absence of symptoms, which leads patients not to an outpatient appointment with a gastroenterologist, but to emergency surgery departments. At the same time, surgeons have to treat not patients with “abstract journal” gastro- and enteropathy, but patients with gastrointestinal bleeding and perforations, which are life-threatening complications of NSAID-induced ulcers. The results of this treatment remain very disappointing: the overall mortality rate when bleeding or perforation of NSAID-induced ulcers occurs both in the gastroduodenal zone and in the small intestine reaches 27–30%.

It is obvious that the wide range of side effects of traditional NSAIDs on the digestive system is not limited only to their gastrotoxicity. An equally significant problem associated with the widespread use of NSAIDs is the hepatotoxic potential of this group of drugs. At first glance, the targets of the toxic effects of NSAIDs are different - the mucous membrane of the digestive tube and the liver parenchyma. However, talking about multidirectional side effects of this group of drugs would be too simplistic. It seems that gastro- and hepatotoxicity of NSAIDs may be links in one pathogenetic chain, one of the final consequences of which may be the occurrence of massive hemorrhage from the upper digestive tract, which again is within the competence of surgeons.

Unfortunately, the problem of the toxic effects of NSAIDs on the digestive tract is not limited to describing only individual clinical cases. According to our American colleagues, the probability of death from complications of therapy with nonsteroidal drugs is comparable to that from malignant neoplasms and tobacco smoking and is many times higher than the probability of death from road traffic accidents or domestic accidents. Taking into account the high frequency of toxic effects of drugs on the digestive tract, as well as the difficulties of diagnosing and treating patients with this pathology, most modern researchers in their works emphasize that only targeted pathogenetically based prevention can be the only means that can prevent the often fatal complications of therapy NSAIDs, and thereby save the patient’s life.

The choice in each specific case of a particular NSAID is obviously determined by the balance of its effectiveness and safety. Analysis of domestic and foreign studies on NSAID therapy makes it possible to conclude that modern non-steroidal drugs (diclofenac, naproxen, ibuprofen, ketoprofen, nimesulide, meloxicam, celecoxib) are quite effective in terms of their impact on the local or systemic inflammatory response, nociceptive pain and hyperthermia. comparable to each other. An example is the report by R. Deyo et al. (2008), based on data from the Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews, a meta-analysis of 65 multicenter studies (11,237 patients) assessing the effectiveness of NSAIDs for dorsalgia. Based on the study, the authors concluded that today there is clear evidence that modern NSAIDs, including COX-2 inhibitors (coxibs), have similar anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity and comparable clinical efficacy. However, as practice shows, the preference for a particular drug based on the criterion of its effectiveness is, as a rule, determined by a purely subjective factor, namely, the doctor’s personal experience. On the other hand, the choice of an NSAID based on the criterion of its safety in relation to the digestive tract should be based only on the objective factor of the toxic potential of this drug on the mucous membrane of the digestive tube and on the hepatic parenchyma.

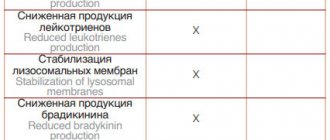

The toxic potential of each specific NSAID to the gastrointestinal mucosa should be considered using only the alternative assessment of whether the drug is safe or not. Considering that as the dose of almost all NSAIDs increases, their damaging effect on the mucous membrane of the digestive tube increases, the criterion for the safety of a nonsteroidal drug is its absence of dose-dependent gastrotoxicity (diagrams 1, 2, 3). In turn, the dose-dependent gastrotoxicity itself is determined by the non-selective inhibition of both isoenzymes of cyclooxygenase types 1 and 2 (COX-1 and COX-2) by traditional NSAIDs. It is for this reason that in the classifications of the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European European Medicines Agency (EMEA), all NSAIDs are divided into selective COX-2 inhibitors (coxibs), which do not have dose-dependent gastrotoxicity and are therefore safe in relation to the mucous membrane of the digestive tube, and non-selective COX-2 inhibitors (all other NSAIDs), which have dose-dependent gastrotoxicity and therefore damage the mucous membrane of the digestive tube. The grading of NSAIDs used by some domestic authors into “selective and highly selective COX-2 inhibitors”, or into “non-selective, selective and highly specific COX-2 inhibitors”, implying the presence of a quantitative difference in selectivity, introduces a lot of confusion into the work of the practitioner and, obviously, does not should be applied. Currently, there is only one class of non-steroidal drugs that do not have dose-dependent gastrotoxicity and are therefore safe against the mucous membrane of the digestive tube, namely coxibs, the only representatives of which registered in Russia are celecoxib and etoricoxib.

The toxic effect of NSAIDs on the hepatic parenchyma is another factor that determines the need for a differentiated approach when prescribing one or another non-steroidal drug to each specific patient. Most researchers emphasize that the risk of drug-induced liver damage increases in the presence of chronic diffuse liver disease of any etiology. At the same time, disturbances in drug metabolism are directly proportional to the signs of chronic hepatic cell failure, which is most pronounced in liver cirrhosis. As indicated by H. Tan et al. (2007), the clinical and morphological forms of the toxic effects of NSAIDs on the liver can be very variable: acute hepatitis, cholestasis, cholestatic hepatitis, granulomatous hepatitis, which tends to become chronic, chronic cholestasis with ductopenia, yellow liver atrophy, manifested by fulminant liver failure. N. O'Connor et al. (2003) cites the two mechanisms of damage to the liver parenchyma by NSAIDs most often mentioned in the literature: 1) hypersensitivity reactions, 2) metabolic damage (aberration). R. Bort et al. (1999), based on a generalization of experimental data, presented the sequence of events when hepatocytes are damaged by NSAIDs as follows. The main target of NSAIDs at the subcellular level is mitochondria. In the process of metabolism of NSAIDs by cytochrome P450, NSAID derivatives are formed, which are able to influence the processes of electron transfer in the respiratory chain on the cristae of mitochondria, leading to disruption of oxidative phosphorylation, ATP synthesis and energy deficiency in the cell. It is possible that native NSAIDs also have a toxic effect on mitochondria. Disruption of the processes of oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria and microsomal oxidation of some NSAIDs (for example, naproxen) lead to the activation of free radical oxidation, which ultimately results in membrane disorganization, death of the hepatocyte and syntopic cellular structures (bile duct cells). It is possible that in the process of disorganization, the cytolemma acquires antigenic properties, which leads to the induction of an autoimmune response and morphologically manifests itself as periportal edema and homonuclear infiltration.

According to L. Garcia-Rodriguez et al. (1994), C. Sgro et al. (2002), I. Lacroix et al. (2004) risk factors for the development of NSAID-induced liver damage should include: female gender of the patient, age over 56 years, the presence of a chronic autoimmune disease, the presence of chronic diffuse liver disease, decreased renal function, hypoalbuminemia, high-dose NSAID therapy, the presence of a chronic disease requiring taking NSAIDs, polypharmacy.

When prescribing NSAIDs for a long course or when treating patients with manifestations of “idiopathic” liver failure, one should remember the possibility of transforming the hepatoxic potential of NSAIDs into real liver damage with difficult-to-control consequences in the form of fulminant liver failure and hepatorenal syndrome. Considering the extremely limited possibility of liver transplantation in Russia, for most patients such complications of NSAID therapy become fatal. Obviously, from a clinical and economic point of view, it is more expedient not to passively control possible manifestations of hepatotoxicity (which can very quickly become an uncontrollable process in itself), but to exclude the very cause of hepatotoxicity. Moreover, a number of NSAIDs are available for modern clinical practice, whose hepatotoxicity is minimal. kidney situation resulting from long-term and non-selective NSAIDs leads to an imbalance in the endothelin system (vasoconstriction)

In an extensive analytical report, J. Rubenstein et al. (2004), which is the result of a meta-analysis of 8 clinical studies of NSAID hepatotoxicity, in addition to the established overall risk of clinically significant NSAID-induced liver damage in the population (4.8 - 8.6 / 100,000 patients per year), provides data on individual differences in hepatotoxic potential modern NSAIDs. Sulindac and indomethacin have the greatest potential for NSAID-induced hepatotoxicity. Based on the results of the studies, the selective COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib and the traditional NSAID naproxen have the least hepatotoxicity.

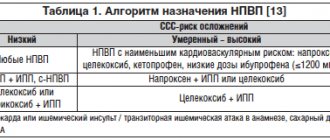

Thus, choosing a gastrointestinal safe NSAID is a very difficult task, requiring the assessment of a number of factors. Such an assessment can be presented in the form of step-by-step algorithms for choosing the most safe NSAID for the mucous membrane of the digestive tube and hepatic parenchyma.

The first stage of the algorithm for choosing a NSAID that is safe for the mucous membrane of the digestive tube (Fig. 1) is a careful and balanced assessment of the indications for prescribing NSAIDs. The main indication for the use of NSAIDs is a local or systemic inflammatory reaction of any etiology (infectious process, trauma, autoimmune reactions). Although the presence of pain and hyperthermia, which are manifestations of inflammation, serves as a basis for prescribing NSAIDs, the latter should not be the drugs of choice for “pure” analgesia or fever relief. NSAIDs should be prescribed for pain only if there is a proven noceceptive component, excluding the neuropathic nature of the pain. Let us recall that a number of drugs are currently purposefully used to relieve neuropathic pain, the most effective of which is pregabalin (Lyrica®). A differentiated approach to analgesia is necessary not only for pathogenetic, and therefore effective therapy of pain, but also to prevent unjustified (usually long-term and high doses) prescription of NSAIDs. Likewise, selective targeting of hyperthermia when the inflammatory response is mild should not be the primary reason for prescribing NSAIDs; in this situation, acetaminophen, for example, should be preferred.

The next stage of the algorithm is to estimate the expected duration of the course of NSAID therapy. It is known that already after 7 days from the start of treatment, non-steroidal drugs can cause the formation of erosions and ulcers against the background of the initially intact mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum. Therefore, from the point of view of potential gastrotoxicity, NSAID therapy should be divided into short-term (less than 7 days) and long-term (more than 7 days). Considering the fact that even a short-term prescription of NSAIDs for “compromised” mucosa can cause damage to it, the decision to use short-course NSAID therapy requires the mandatory implementation of the next stage of the algorithm - assessing risk factors for the development of NSAID gastropathy. These include: use of NSAIDs in the maximum allowable dosage, combined use of two or more NSAIDs, combination of NSAIDs with glucocorticoids, previous use of NSAIDs for more than 3 months, patient age over 65 years and, finally, a history of peptic ulcer disease, previously verified acute stress -ulcers or NSAID-induced ulcers. The absence of these risk factors for the occurrence of NSAID gastropathy makes it possible to prescribe traditional NSAIDs in average therapeutic doses with a duration of therapy of no more than 7 days. The presence of at least one or, especially, several risk factors for the development of NSAID gastropathy determines the impossibility of even short-term therapy with traditional NSAIDs and, at the same time, the need to use selective COX-2 inhibitors, coxibs, that are safe for the mucous membrane of the digestive tract. Long-term therapy with non-steroidal drugs, in itself being a risk factor for the development of NSAID-induced erosions and ulcers, obviously requires the use of coxibs. It should be recalled that the possible variability in the dosage of celecoxib (from 100 to 800 mg/day) does not affect its safety in relation to the mucous membrane of the digestive tract and makes it possible to carry out effective therapy with this drug for inflammation and pain of varying severity.

A fundamentally important point when prescribing NSAIDs is to assess the patient’s ulcer history. If there are subjective complaints (characteristic epigastric pain, dyspepsia) or objective anamnestic data indicating the possibility or fact that the patient has a pathology of the gastroduodenal zone, before prescribing any NSAIDs for any expected duration of therapy, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGDS) is mandatory. The presence of gastritis, duodenitis, erosions and, especially, ulcers of the stomach or duodenum completely excludes the possibility of using all traditional (non-selective for COX-2) NSAIDs and requires specific therapy, primarily antisecretory drugs (proton pump inhibitors: omeprazole 40 mg /day). In the case of an uncomplicated erosive-ulcerative process in the stomach or duodenum and, at the same time, there is an urgent need to prescribe NSAIDs, the simultaneous use of celecoxib and proton pump inhibitors, carried out under the control of endoscopy (weekly examination), is fundamentally possible. It follows from this that even when prescribing celecoxib as an NSAID, before starting therapy one should not neglect the clinical (and, if necessary, instrumental) assessment of the condition of the gastroduodenal mucosa, since undiagnosed erosive and ulcerative lesions make it erroneous to prescribe celecoxib alone without antisecretory agents. funds.

The prescription of NSAIDs, taking into account their potential hepatotoxicity, may also have the nature of an algorithm (Fig. 2) similar to the algorithm for choosing a non-steroidal drug that is safe for the gastroduodenal mucosa. At the first stage, by analogy with the algorithm described above, the indications for prescribing NSAIDs (local or systemic inflammatory reaction) are assessed. Risk factors for NSAID hepatotoxicity are then assessed. It should be remembered that all modern NSAIDs have hepatotoxic potential. On the other hand, the quantitative criterion of hepatotoxicity allows us to divide all NSAIDs into drugs with a relatively high hepatotoxic potential (sulindac, ibuprofen, nimesulide) and drugs with a relatively low hepatotoxic potential (naproxen, celecoxib). In addition, a clear time interval between the start of NSAID therapy and the occurrence of damage to the liver parenchyma has not yet been established. Therefore, dividing NSAID therapy into short-term and long-term (by analogy with gastrotoxicity) from the point of view of realizing their hepatotoxic potential is incorrect: the development of cytolytic or cholestatic syndrome is possible within a few days from the start of therapy. Risk factors for NSAID hepatoxicity include: patient age over 65 years, presence of an autoimmune disease, renal failure, hypoalbuminemia, taking more than one NSAID or taking NSAIDs at the maximum dose, simultaneous administration of a large number of drugs and, finally, the most significant - the presence of underlying liver pathology . It should be noted that the mere presence of acute liver pathology with cytolysis or cholestasis syndromes, especially complicated by hepatic cell failure, should be a contraindication to the prescription of NSAIDs. The possibilities of NSAID therapy against the background of chronic diffuse liver disease are also very limited. Thus, in the presence of chronic diffuse liver disease, before prescribing NSAIDs, it is mandatory to study biochemical markers of hepatocyte cytolysis and cholestasis syndromes: ALT, AST, GGTP, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase. An excess of these indicators by 2 or more times relative to the upper limit of normal indicates the impossibility of NSAID therapy. In the case of chronic diffuse liver disease, but a slight deviation (not exceeding the norm by more than 2 times) of the above biochemical parameters, NSAID therapy is possible, but it is necessary to use drugs with minimal hepatotoxic potential (naproxen, celecoxib). If the patient does not have risk factors for hepatoxicity, it is theoretically possible to use any officially registered NSAID. However, in practice, you should still refrain from using NSAIDs with proven hepatoxicity - sulindac, ibuprofen and nimesulide. In addition, regardless of the hepatotoxic potential of the NSAID used in each specific case, dynamic monitoring of biochemical markers of hepatic cytolysis and cholestasis is necessary, since the occurrence of drug-induced liver damage is a very difficult to predict situation. With long-term NSAID therapy, the frequency of such monitoring should be at least once a month.

In conclusion, we consider it necessary to emphasize once again that at present, with almost similar effectiveness of most modern NSAIDs, the criterion of its safety should come to the fore when choosing a specific treatment option. The priority of this particular criterion, which forms the basis of the presented algorithms aimed at preventing or minimizing the side effects of NSAIDs from the digestive tract, will avoid uncertain balancing on the virtual edge of “efficacy vs. safety" and conduct treatment in conditions of maximum comfort for both the patient and the doctor.

Bibliography:

- An Evidence-Based Approach to Prescribing Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs. Third Canadian Consensus Conference. The Journal of Rheumatology 2006; 33:1.

- Bareille MP, Montastruc JL, Lapeyre-Mestre M. Liver damage and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: case non-case study on the French pharmacovigilance database. Therpaie 2001; 56:51–5.

- Bjorkman D. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug associated toxicity of the liver, lower gastrointestinal tract and the esophagus. Am J Med 1998; 105:17–21S.

- Bombardier C. An evidence-based evaluation of the gastrointestinal safety of coxibs // Am. J. Med. - 2002. - No. 89: (suppl.). - P. 3D-9D. 117

- Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews, 2008, Issue 1.

- Crofford LJ, Lipsky PE, Brooks P. et al. Basic biology and clinical application of specific cycloxygenase-2 inhibitors // Arthritis Pheum, 2000. - No. 43. - P. 33 157-33 160.

- Deny S., Loke YK Risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage with long term use of aspirin // BMJ. - 2000. - No. 321. - P. 1183-1187.

- Fitzgerald GA, Patrono C. The Coxibs, selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase-2 // New Engl. J. Med. - 2001. - Vol. 345. - P. 433-442.

- Fries JF NSAID gastropathy: the second most deadly rheumatic disease? Epidemiology and risk appraisal. J Rheumatol, 2000, 58(Suppl 28), 6-10.

- Garcia-Rodriguez LA et al. Risk of hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding associated with Ketorolac, other NSAIDs, calcium antagonists, and other antihypertensive drugs // Arch. Intern. Med. - 1998. - No. 158. - P. 33-39.

- Goldstein JL, Silverstein FE, Agrawal NM et al. Reduced risk of upper gastrointestinal ulcer complications with celecoxib, a novel COX-2 inhibitor. Am J Gastroenterol, 2000, 95, 1681-1690

- Goldstein JL, Silverstein FE, Agrawal NM et al. Reduced risk of upper gastrointestinal ulcer complications with celecoxib, a novel COX-2 inhibitor. Am J Gastroenterol, 2000, 95, 1681-1690

- Greaves RR, Agarwal A, Patch D, et al. Inadvertent diclofenac rechallenge from generic and non-generic prescribing, leading to liver transplantation for fulminant liver failure. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001; 13:71–3

- https://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/press/pr/24732305en.

- https://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/cox2/

- Lanas A. et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1685 – 1693.

- Maddrey WC, Maurath CJ, Verburg KM, et al. The hepatic safety and tolerance of the novel cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib. Am J Ther 2000; 7:153–8.

- Merlani G, Fox M, Oehen HP, Cathomas G, Renner EL, Fattinger K, Schneeman M, Kullak-Ublick GA. Fatal hepatotoxicity secondary to nimesulide. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2001; 57:321–6.

- Pincus T., Swearingen C., Cummins P. at al. Preference for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs versus acetaminophen and concomitant use of both types of drugs in patients with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol, 2000, 27, 1020-1027.

- Rabinovitz M, Van Thiel DH. Hepatotoxicity of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Gastroenterol 1992; 87:1696–704.

- Riley TR, Smith JP. Ibuprofen-induced hepatotoxicity in patients with chronic hepatitis C: A case series. Am J Gastroenterol 1998; 93:1563–5.

- Rodriguez-Gonzalez FJ, Montero JL, Puente J, et al. Orthotopic liver transplantation after subacute liver failure induced by therapeutic doses of ibuprofen. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2476–7.

- Sgro C, Clinard F, Ouazir K, et al. Incidence of drug-induced hepatic injuries: a French population-based study. Hepatology 2002; 36:451–5.

- Silverstein F. E., Faich G., Goldstein J. L. at al. Gastrointestinal Toxicity With Celecoxib vs Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs for Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis.The CLASS Study: A Randomized Controlled Trial JAMA, 2000, 284, 1247-1255.

- Simon LS, Smolen JS, Abramson SB et al Controversies in COX-2 selective inhibition // J. Rheumatol. - 2002. - No. 29. - P. 1501-1510. Silverstein FE, et al. Ann Intern Med. 1998;123:241–249.

- Singh G, Lanes S, Triadafilopoulos G. The American Journal of Medicine, 2004, 100-106.

- Singh G., Fort J., Goldstein J. et al. Celecoxib versus naproxen and diclofenac in osteoarthritis patients: SUCCESS–1 study. Am. J. Med., 2006, 119, 255–266.

- Singh G., Rosen RD NSAID-induced gastrointestinal complications: the ARAMIS perspective-1997: Arthritis, Rheumatism, and Aging Medical Information System. J Rheumatol Suppl 1998, 51, 8-16.

- Wongcharatrawee S, Groszmann RJ: Diagnosing portal hypertension. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2000 Dec; 14(6): 881-94.

What non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are most often prescribed for arthrosis?

- Aspirin is indicated in the initial stages of treatment of arthrosis and osteoarthritis, however, patients with diseases of the heart, blood vessels and gastrointestinal tract require special caution.

- Diclofenac - in tablets or ointment form.

- Ibuprofen is one of the most common medications that is easier to tolerate by the body than others.

- Indomethacin - attractive at an affordable price, relieves pain well, but it has many contraindications.

- Ketoprofen - in the form of tablets, injections, ointments, aerosols, gels, suppositories and even a preparation for applications.

- Movalis is less toxic to the gastrointestinal tract than many others, but is contraindicated in patients with diseases of the cardiovascular system.

- Nimesulide – copes with pain and inflammation, and also helps stop the destruction of joints.

- Etoricoxib requires strict adherence to the dosage, otherwise complications from the heart and blood vessels are possible.

There are a lot of drugs in the NSAID group: they must be prescribed by a doctor

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are effective means of controlling acute and chronic pain, widely used in the complex treatment of chronic rheumatic diseases (RDs). At the same time, most rheumatologists consider NSAIDs as a necessary, but only symptomatic, remedy, the use of which can reduce suffering and improve the quality of life of patients, but cannot change the course of the disease [1, 2].

A similar judgment is generally justified with respect to the use of NSAIDs for diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and osteoarthritis (OA). There is still no clinical data confirming the ability of NSAIDs to slow down joint destruction in these nosological forms; Moreover, the use of certain NSAIDs (eg, indomethacin) may contribute to the progression of OA [3].

However, there are RDs in which NSAIDs have not only a symptomatic, but also a clear pathogenetic effect. This is a large group of seronegative spondyloarthritis, in particular ankylosing spondylitis (AS).

The pathogenesis of AS is associated with chronic autoinflammation, which occurs against the background of a hereditary predisposition and is based on a dysregulation of the activity of T-lymphocytes - cytotoxic CD8+ cells (T-killer cells). The main springboard for the pathological process in the onset of AS is the enthesis - the area of attachment of ligaments, tendons and fascia to the bone. Infiltration of this area by lymphohistiocytic cells and hyperproduction of cytokines - interleukins (IL) 1, 6, as well as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) leads to severe destructive inflammation of bone tissue - osteitis [4-6]. Simultaneously with the inflammatory process (against the background of its subsidence or even in the absence of pronounced inflammatory changes), the process of chondroid metaplasia and defective endochondral ossification, which is very characteristic of AS, develops in the area of the affected entheses. The fusion of individual areas of defective osteogenesis leads to the formation of syndesmophytes and ankylosis, which is manifested by progressive dysfunction of the spine [7-9].

As with other RDs, the modern concept of treating AS involves a targeted impact on the main elements of the pathogenesis of this disease. Accordingly, the main “targets” of pharmacotherapy for AS should be considered chronic inflammation and ectopic osteogenesis in the area of entheses and ligaments of the spinal column.

One of the most powerful means of anti-inflammatory therapy is considered to be genetically engineered biological drugs (GEBPs) - anti-cytokine agents, such as TNF inhibitors (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, etc.). These drugs effectively suppress systemic and local manifestations of acute inflammation in AS; however, unlike RA, their structure-modifying effect is absent in this disease [10-12]. To date, the ability of TNF inhibitors to inhibit the formation of syndesmophytes has been shown only with their long-term (6-8 years) use [13-15].

Surprisingly, the “good old” NSAIDs are much more promising in this regard: there are serious reasons to believe that long-term continuous use of these drugs in anti-inflammatory doses allows not only to effectively control the symptoms of AS, but to slow down the radiological progression of this disease [16-18].

NSAIDs, the main action of which is associated with the blockade of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and the suppression of prostaglandin (PG) synthesis, can delay the development of inflammatory tissue damage. After all, PGs are not only pain mediators; these active substances exert many biological effects that underlie the inflammatory response. They cause chemotaxis of the main “aggressors” - neutrophils and macrophages, increase vascular permeability, stimulate degranulation of mast cells, affect the blood coagulation system, stimulate the catabolism of cartilage and bone cells, etc. [1, 19].

One of the most important biological phenomena that determines the chronicity of immune inflammation is neoangiogenesis - the process of active formation of new blood vessels that “grow” into the area affected by the pathological process. The development of granulation tissue, the persistence of chronic synovitis and the formation of pannus in RA, as well as tumor progression are unthinkable without angiogenesis. This process is associated with COX-2, therefore NSAIDs, which are COX-2 inhibitors, can slow down the development of newly formed vascular tissue [20-23]. This pharmacological effect, in addition to the effect on chronic immune inflammation, is largely associated with the antiproliferative effect of NSAIDs, which determines their antitumor potential [23].

It is important to note that many stages of inflammatory aggression, which determine irreversible structural changes, are associated with the expression of COX-2 and hyperproduction of PG (primarily PGE2). These elements of tissue damage include the synthesis and activation of metalloproteinases - aggressive enzymes secreted by macrophages and neutrophils, which are responsible for the destruction of the articular cartilage matrix. This process is mediated by the excitation of surface receptors for PGE2 (EP1-EP4). In addition, the expression of COX-2 is associated with the formation of nuclear transcription factors NF-xB, which is responsible for stimulating the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO) and activation of osteoclasts. It should be noted that the proliferation of immunocompetent cells, in particular B-lymphocytes, is stimulated by activation of receptors for PGE2. This phenomenon has been noted, for example, in B-cell lymphomas [24-26].

At the same time, NSAIDs can suppress the development of ectopic ossification, a process so important for the formation of syndesmophytes in AS. The effect of NSAIDs may be determined by the mechanism of inhibition of osteoclast activation and neoangiogenesis described above. There is indisputable evidence of this pharmacological effect - the practice of using NSAIDs for the prevention of heterotopic ossification (HO) after surgical interventions.

HO is a pathological process that is characterized by massive deposition of calcium crystals in soft tissues after extensive traumatic injury. This pathology often appears after “major” orthopedic operations, such as knee and hip replacement, although usually to a minor extent. However, in some cases, HO is very pronounced, which leads to severe functional disorders, up to a complete block of the affected joint. At the same time, spondyloarthritis, in particular AS, a disease whose progression is accompanied by ossification of the elements of the ligamentous apparatus, is considered a risk factor (RF) for the development of postoperative HO [27, 28]. The use of NSAIDs in the perioperative period can significantly reduce the likelihood of developing this complication, which is confirmed by data from a series of randomized clinical trials. Thus, according to a Cochrane meta-analysis of 17 studies that examined this issue (a total of 4763 patients, the overall effectiveness of NSAIDs turned out to be quite high: the risk of developing HO when taking medium and high (but not low!) doses of these drugs decreased by 59% [29 ].

The symptomatic effect of NSAIDs in AS is beyond doubt; These drugs effectively and quickly reduce pain and improve the function of the joints and spine. Moreover, their therapeutic potential is determined largely by anti-inflammatory rather than analgesic effects, which is confirmed by a significant advantage compared to placebo and central analgesics.

It should be noted that the placebo effect in patients with chronic pain is very pronounced; which is clearly visible when analyzing the effect of various analgesics in such nosological forms as OA and pain in the lower back. Thus, according to a meta-analysis by R. Moor [30], the effectiveness of NSAIDs in OA exceeds the results of using placebo by only 20-30%.

With AS, the situation is completely different, especially when it comes to relieving symptoms clearly associated with inflammation, such as night pain and morning stiffness. As an illustration, we can cite data from a 52-week study by D. van der Heijde et al. [31], who studied the comparative effectiveness of etoricoxib at a dose of 90 and 120 mg, as well as naproxen at a dose of 1000 mg/day in 387 patients with AS. At the beginning of the study (first 6 weeks), one of the patient groups received placebo; against the background of such “therapy,” there was a decrease in pain severity by an average of 12.6 ± 2.3 mm (according to a 100-mm visual analogue scale - VAS). However, NSAIDs are much more effective: etoricoxib reduced pain by 41.5 ± 1.6 mm, and naproxen by 33.7 ± 2.3 mm. The differences are especially obvious when analyzing the reduction in night pain (scale 0-3 points): –0.18±0.06, –0.87±0.04 and –0.63±0.06, as well as the duration of morning stiffness: – 5.5, –29.3 and –25.1 minutes, respectively. In total, the proportion of therapy interruptions due to ineffectiveness was 47.3% in the placebo group, 7.8% (120 mg) and 9.8% (90 mg) in the etoricoxib groups, and 20.2% in the naproxen groups [31].

Similar results were obtained in the work of M. Dougados et al. [32], who conducted a 6-week comparison of the effectiveness of celecoxib, ketoprofen and placebo in 246 patients with AS. The difference in the reduction in the total pain score (VAS) was not so great: in the placebo group 3±29, ketoprofen 21±26, celecoxib 27±30 mm. However, with regard to night pain, the difference turned out to be very significant: –0.2 ± 29.3, –16.0 ± 31.7 and –17.7 ± 39.3, respectively, as well as with regard to the duration of morning stiffness: +7 ± 128 , –27±154 and –28±74 min, respectively.

Recently, more and more clinical data have accumulated confirming the ability of NSAIDs not only to relieve symptoms, but also to slow down the development of AS.

Thus, the results of a study were recently published showing the ability of NSAIDs to significantly reduce the activity of AS, up to the development of remission of the disease. J. Sieper et al. [33] compared the effectiveness of the combination of infliximab (5 mg/kg, classical regimen) + naproxen 1000 mg/day and naproxen 100 mg/day alone in 156 patients with AS. Combination therapy with GEBD and NSAIDs turned out to be more effective: partial remission according to ASAS criteria after 6 months of treatment was achieved in 61.9% of patients ( p

=0.002). Moreover, in the control group, a similar result (which came as a surprise) was also achieved in a fairly large, albeit smaller number of patients - 35.3%.

Probably one of the first studies to show the beneficial effect of NSAIDs on reducing the rate of progression of AS was the work of J. Boersma published in 1976 [34]. This is a retrospective analysis of the use of phenylbutazone (a pyrazolone derivative), a drug that is not currently used due to the risk of developing hematological complications, but was previously considered one of the “strongest” NSAIDs. Having assessed the results of treatment in 40 patients with AS, the author noted the best result (absence or significant slowdown in spinal ossification) in patients who regularly took phenylbutazone; moderate results were observed in patients who received this drug irregularly, and rapid development of ossification in individuals who did not receive therapy [34].

The most important confirmation of the structure-modifying effect of NSAIDs in AS should be considered the work of A. Wanders et al. [35]. In this study, 205 patients with AS received celecoxib at a dose of 200 mg/day for 2 years; 50% of them daily, regardless of the presence of symptoms, and the second 50% - only if necessary to relieve pain (“on demand”). The main criterion for assessing the effect of the drug was radiological progression. The researchers used the modified Stoke ankylosing spondylitis spine score (mSASSS), which was calculated at the time of inclusion in the study and at the end of the study. It turned out that the deterioration of the X-ray picture with regular use of celecoxib was observed 2 times less often than with its use “on demand”. Thus, the number of patients with any negative changes and those who had pronounced negative dynamics was 23 and 45%, as well as 11 and 23%, respectively ( p

<0,001).

It should be noted that slowing down the progression of the disease during continuous use of NSAIDs was not associated with a more pronounced anti-inflammatory effect: the dynamics of the ankylosing spondylitis disease activity indices BASDAI (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index) and ASDAS (Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score), as well as laboratory tests in there was no difference between the main and control groups [35].

In November 2011, at the ACR Congress, data from Canadian scientists were presented who conducted a similar comparison of the effectiveness of two NSAID regimens for AS. This work included only 40 patients, but all of them, and this is a fundamental feature that makes the results obtained especially valuable, received GIBD (TNF inhibitors). After 2 years, in patients receiving biological medications without NSAIDs, the average mSASSS score increased by 3.5 points. At the same time, in the group of patients receiving combination therapy, radiological changes practically did not progress—mSASSS increased by an average of only 0.2 points. As can be seen, NSAIDs in combination with TNF inhibitors provide a significantly better pathogenetic effect in AS than biologically active drugs in the form of monotherapy [36].

The pathogenetic potential of NSAIDs is equally clearly demonstrated by the work of D. Poddubnyy et al. [37]. The study group consisted of 164 patients (88 with definite AS and 76 with pre-radiological stage of axial spondyloarthritis), who received NSAIDs for 2 years. It turned out that the rate of radiological progression in patients who regularly took NSAIDs in medium and maximum doses was significantly lower than in people who received these drugs in small doses “on demand”. This is especially clearly seen in the subgroup of patients who initially had syndesmophytes and who had obvious systemic inflammatory activity (increased levels of C-reactive protein - CRP). Thus, the average mSSSA value in those regularly taking NSAIDs was only 1.81, while in those taking these drugs “on demand” it was 4.36 ( p

=0,02) [37].

The baton of evidence for the pathogenetic role of NSAIDs in the treatment of AS was taken up by French scientists M. Blachier et al. [38]. They observed 475 patients with AS DESIR (Devenir des Spondylarthropathies Indifferenci?es R?centes, “Outcomes of undifferentiated spondyloarthropathies”), assessing the dynamics of radiological signs of the axial skeleton. The presence of obvious damage was noted in 180 (37.9%) patients. Further analysis made it possible to identify factors influencing the development of skeletal pathology. Thus, alcohol intake, increased CRP levels, and the presence of signs of sacroiliitis according to magnetic resonance imaging were associated with the progression of AS; the only factor associated with freedom from injury was a good response to NSAID therapy (weighted odds ratio 0.44) [38].

Thus, there are quite good reasons to assert that NSAIDs can slow down the development of AS. However, this effect appears to be only partly determined by the anti-inflammatory effect of NSAIDs; It can be assumed that NSAIDs are able to suppress pathological bone proliferation with the formation of syndesmophytes, which underlies the progression of irreversible changes in the spine in this disease [39, 40].

Therefore, the regular use of NSAIDs should be considered one of the main directions of modern pharmacotherapy for AS [41]. Of course, when discussing the possibility of pathogenetic use of NSAIDs, one cannot discount the problem of side effects [42]. The structure-modifying properties of NSAIDs appear when they are taken over a long period of time in therapeutic doses. In this situation, the risk of developing class-specific complications, primarily in the form of disturbances in the structure and function of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and cardiovascular system (CVS), may become the main factor limiting the therapeutic potential of these drugs [19].

Many patients with AS may have a moderate or high risk of developing complications in the form of disruption of the structure and function of the upper gastrointestinal tract. This is indicated by data from our examination of 614 patients with various forms of spondyloarthritis who were hospitalized at the NIIR clinic from 1996 to 2004 and underwent endoscopic examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Among them, 60.1% were young and middle-aged men: 85% were people under 50 years of age.

A significant number of those examined had standard risk factors: a history of ulcers in 18.9%, dyspepsia in 67.5%, taking high doses of NSAIDs in 16.6%. Moreover, multiple erosions (>10) and/or gastrointestinal ulcers were detected in 16.5% of patients [43].

J. Zochling et al. [44] assessed the safety of NSAIDs in 1080 patients with AS who received these drugs for at least 12 months in clinical practice. The most commonly used drugs were diclofenac, naproxen and indomethacin. According to the data obtained, at least 25% of patients noted the development of various side effects, most often gastralgia, headache and dizziness, as well as nausea. No dangerous complications were reported. The incidence of side effects varied significantly depending on the NSAIDs used; in those taking indomethacin, their number reached 31.4%, celecoxib - only 10.5% [44].

The well-known association between AS and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) may also cause serious concern. We can talk not only about clinically obvious forms of this pathology; Many patients with AS (according to various sources, almost 50%) experience asymptomatic inflammation of the mucous membrane of the small intestine, accompanied by an increase in its permeability. These changes can be regarded as a serious risk factor for the development of NSAID-induced enteropathy, exacerbation or complications of IBD [45-47].

Complications in the form of disruption of the structure and function of the cardiovascular system can also be significant. Although patients with AS who require active anti-inflammatory therapy are mostly young people, they nevertheless have an increased risk of developing CVD. This is determined by more rapid progression of atherosclerosis and prothrombotic disorders of hemostasis associated with systemic inflammation [48, 49]. In this regard, the work of Y. Huang et al. is very important. [50], who studied the risk of developing coronary heart disease (CHD) in patients with AS. These scientists compared the incidence of CAD in a cohort of 4,794 patients with AS and 23,970 individuals without RD and matched for sex and age over a 3-year period. The risk of developing coronary artery disease was clearly higher in the cohort of patients with AS: risk ratio 1.47 (1.13-1.92) [50].

At the same time, effective elimination of the main symptoms of AS (primarily chronic pain) and suppression of systemic inflammation while taking NSAIDs can have a positive effect on the life expectancy of patients. For example, G. Bakland et al. [51], who observed a cohort of 667 patients with AS, noted the lack of regular NSAID treatment as an important factor reducing patient survival (standardized risk of death 4.35).

Nevertheless, the possibility of developing complications requires serious responsibility from the doctor and careful consideration of risk factors in the form of disturbances in the structure and function of both the gastrointestinal tract and the cardiovascular system [2, 19]. A rational choice of NSAIDs (for example, the use of selective COX-2 inhibitors in patients with concomitant gastrointestinal pathology or, on the contrary, non-selective NSAIDs with the best cardiovascular tolerability - naproxen, in combination with gastroprotectors) in people at risk of developing cardiovascular complications can significantly reduce risk of side effects and increase the likelihood of therapeutic success. With long-term use of NSAIDs, regular examinations of patients are necessary (including general and biochemical blood tests, and, if necessary, esophagogastroduodenoscopy) at least once every 3-6 months.

What you need to remember when taking an NSAID drug

Medicines in this category have a fairly quick pain-relieving effect, so many patients do not deny themselves an “extra pill.” In fact, this approach is very dangerous, since an overdose is fraught with serious complications. Therefore, doctors strongly recommend:

- take such medications only as prescribed by a doctor and in the dosage indicated by him;

- do not combine the use of several drugs from this group at once;

- take medications only with water, since tea, coffee, juice or milk distort the effect of the drug;

- do not self-medicate.

Simultaneous use of non-steroidal drugs and alcohol is incompatible and life-threatening

Treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs alone is ineffective. This is only part of complex therapy for age-related or post-traumatic arthrosis. To restore joint mobility, it is necessary to undergo a course of intra-articular injections, for example, Noltrex, to eliminate the deficiency of synovial fluid in the joint capsule and stop painful friction of cartilage. In some cases, long-term use of chondroprotectors, physiotherapy and other therapeutic methods are indicated. Only an integrated approach will bring results.