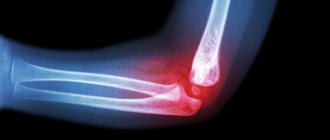

An ulnar collateral ligament injury, such as a sprain or tear, is an injury to one of the ligaments on the inside of the elbow. The ulnar collateral ligament is a structure that helps maintain normal interaction between the humerus and the ulna (one of the bones of the forearm). This ligament is injured during throwing (certain sports) or after elbow dislocation or surgery.

The damage can be a sudden rupture or a gradual stretching of the ligament due to repeated injuries. This ligament is rarely damaged by daily activities. The ligament prevents the elbow from twisting inward. When a ligament ruptures, as a rule, independent healing does not occur, or as a result of regeneration, the ligament lengthens.

Sprains are divided into three degrees. In the first degree of sprain, the ligament is not elongated, but painful. In a second-degree sprain, the ligament is stretched but still functional. In a third degree sprain, the ligament is torn and does not work.

Risk factors

Most injuries occur in the CL when throwing objects overhead, especially in baseball players. Typically, the injury is caused by repeated overuse, which ultimately weakens the ligament significantly and eventually leads to its rupture. Other risk factors include:

- Contact sports (football, rugby) and sports in which falls on an outstretched arm occur, which often leads to dislocations.

- Throwing sports such as baseball and javelin throwing

- Sports that involve overhead arm movements (volleyball and tennis)

- Poor physical condition (weak muscle strength and flexibility)

- Incorrect throwing mechanics

Muscles of the elbow joint proper

In the elbow joint, according to its structure and existing movements, it is possible to determine the presence of two muscle groups: one located in front of the frontal axis - flexors (flexors forward), and the other behind - extensors (flexors backwards).

Among the forward flexors is the already familiar biceps brachii muscle, which passes through two joints (Fig. 35-5). It, as is already known, passes to the forearm, where it gives rise to two tendon bundles; one on the radial side - to the radius, the other - on the ulna, to the fascia of the forearm. Acting with both bundles on the forearm, turned with the palmar surface forward, it participates in flexion of the elbow joint.

Deeper than the biceps brachii there is a second muscle that produces flexion, the internal brachialis.

Internal brachialis muscle

(m. brachialis internus, Fig. 38-12) wraps its beginning around the attachment of the deltoid muscle, comes from the anterior lateral and anterior medial surface of the humerus and both intermuscular septa (septum intermusculare internum et externum). Directing downward, it covers the front of the humerus and elbow joint and, like any muscle adjacent close to the joint capsule, gives part of its fibers to the latter, which, by pulling back the folds of the capsule formed during flexion, prevent it from being pinched. It is attached slightly below the edge of the coronoid process of the ulna, to the tuberosity located here. Most of its fibers go straight down and only the outermost and inner ones have a converging direction. In front, the internal brachialis muscle is covered by the biceps brachii muscle, but on the sides (outside and inside) it protrudes so that during its contraction it can protrude directly under the skin (Fig. 35-18, 18′).

Having an almost parallel direction of the fibers, it gives a resultant that crosses the frontal axis in the middle and at a right angle, and therefore produces only one forward flexion, which it can produce in any position of the forearm (supinated and pronated), which is impossible to the same extent for other muscles , taking part in bending.

With the upper support, the internal brachialis muscle applies its force close to the support of the lever and, therefore, can produce movements in large arcs, expending more force. With a lower support (on the ulna, for example, in a hanging position), the application of force of the internal brachialis muscle is far from the support, and in this case it can exert significantly more force during its contraction. Compared to the biceps brachii muscle, the arc of its movements is smaller, so as the fibers are somewhat shorter.

Innervation: musculocutaneous nerve (n. musculocutaneus, CV-VI).

Having drawn the resultant of the two flexors considered - the internal brachii muscle and the biceps muscle - it is easy to notice that when flexing, the forearm with its distal end should have deviated outward, since both of these muscles apply their forces to the ulnar side of the forearm. Considering the articular surface of the distal end of the humerus, we see that in most cases the groove on the trochlear surface of the humerus is directed from back to front and from the outside to the inside, due to which flexion at the elbow joint occurs mostly with an inward deviation from the midline of the limb. Consequently, among the flexors of the forearm there must also be a muscle that would translate the overall resultant inward and apply its force along the outer part of the forearm. We actually find such a muscle in the form of the brachioradialis muscle.

Brachioradialis muscle

(m. brachio-rad.ialis, Fig. 40-5) starts from the lower third of the outer edge of the humerus and from the external intermuscular septum attached here, runs along the anterior surface of the radial edge of the forearm and ends, attaching to the lower end of the ray, above its styloid process (Fig. 41-7); in addition, it also gives rise to a fibrous process that passes to the aponeurosis of the anterior part of the forearm, to the bracelet-shaped ligament (lig. annulare carpi).

Previously, it was believed that the brachioradialis muscle only rotates the forearm outward (supinates), therefore in many manuals it is also called the long supinator (m. supinator longus). Teyle was the first to notice that it mainly produces flexion at the elbow joint. In fact, she participates in both movements. When the forearm is turned inward (pronated), the muscle, enveloping the beam in a long spiral, crosses the transverse and longitudinal axes of the forearm, therefore, in addition to flexion, it is able to rotate the forearm outward (Fig. 35-77, 42-7). On the contrary, if the forearm is turned outward, its resultant crosses mainly the transverse axis of the elbow joint and participates, together with other muscles, in flexing the forearm. Duchesne believes that its participation in external rotation is very insignificant, and finds that with isolated action and a pre-supinated forearm, this muscle is capable of producing flexion simultaneously with internal rotation. Welker believes that it moves the radius in two directions:

- from extreme pronation brings the hands to the middle position

- from extreme supination it also brings the hand to the middle position.

Therefore, he attributes to it the importance of holding the radius in the middle position and calls it regulator radii. In the absence of the brachioradialis muscle, a change occurs in the shape of the articular surface of the humerus: it is the deviation of the groove on the trochlear surface outward, as a result of which the forearm deviates outward when flexed. Consequently, the presence of this muscle contributes to the inward deviation of the distal end of the forearm.

Rice. 40. Muscles of the palmar superficial layer of the forearm. (Braus.) 1 - distal attachment of the biceps brachii muscle, 2 - extensor carpi radialis longus, 3 - brachioradialis muscle, 4 - extensor carpi radialis brevis, 5 - flexor carpi radialis, 6 - flexor pollicis longus, 7 - long abductor pollicis muscle, 8 - deep plate of the fascia of the forearm, into which the fibers of the tendon of the brachioradialis muscle pass, 9 - fascia of the eminence of the thumb, 10 - annular ligament of the osteofibrous sheath of the finger, 11 - its cruciate ligament, 12 - internal intermuscular septum, 13 - internal muscle of the shoulder, 14 - triceps extensor brachii, 15 - round rotating forearm medially, 16 - internal condyle of the humerus, 17 - tendinous pedicle of the biceps brachii to the aponeurosis of the forearm (lacertus fibrosus), 18 - long palmaris muscle, 19 - ulnar flexor of the carpal joint, 20 - common superficial flexor of the fingers, 21 - palmar transverse carpal ligament, 22 - short palmaris muscle, 23 - palmar aponeurosis, 24 - fascia of the eminence of the fifth finger, 25 - transverse fibers of the palmar aponeurosis, 26 - swimming ligament

The brachioradialis muscle, in contrast to the two flexors just described, applies its force very far from the support, and, acting in conjunction with another muscle (see below), which rotates the forearm medially (pronator teres), also applies its force far from the support , may exert greater force when flexing the forearm. That the muscular apparatus, when bending the forearm forward, can produce not only movements in large arcs, but with the combined action of all its parts can also exhibit great strength - we are convinced of this not only by experience, but also by the size of the muscle attachment surfaces: the sum of all support surfaces and the application of flexor forces is very high.

Innervation: radial nerve (n. radialis, CV-VI).

The second muscle group, located behind the frontal plane of the elbow joint, is a group of extensors.

It appears here in the form of the so-called triceps extensor brachii

(m. triceps brachii, Fig. 39-8, 9, 10) and its extension,

the fourth

, shorter head -

the ulnar muscle

(m. anconaeus quartus). Therefore prof. Lesgaft considers it more correct to unite all four heads under the name of the quadriceps brachii muscle (m. quadriceps brachii). Between its first three heads there is a long head (caput longura, sm anconaeus longus, Fig. 39-9), which starts from the upper part of the outer edge of the scapula, from the articular tubercle (tuberculum infraglenoidale scapulae), immediately under the articular surface, is directed downward and passes into a strong, wide tendon. The second external head (caput laterale, sm anconaeus externus, Fig. 39-10) begins from the upper two thirds of the outer and posterior surface of the humerus and from the external intermuscular septum; finally, the third, internal head (caput mediale, sm anconaeus internus, Fig. 39-6*) begins at the top near the attachment of the teres major muscle, from the internal intermuscular septum, from the entire internal edge and posterior surface of the humerus, and below from the lower third of the outer edge of the humerus. Between the beginning of the internal and the overlying attachment of the external head along the posterior surface of the humerus there is a groove through which blood vessels and nerves pass. All three heads pass into one tendon, which attaches to the olecranon process of the ulna and partly to the aponeurosis of the forearm.

* (A preparation of such an anomaly was described by Prof. P.F. Lesgaft and is kept in the Museum of the Military Medical Academy. With this anomaly, the shoulder joint was also changed, since compensatory movement had to occur in it to be able to bring the arm to the midline of the body.

)

If only these three heads existed, then when bending back (extension), their resultant would be deflected inward; In addition, being attached to the olecranon process close to the support of the lever, the muscle could not exert much force. But here there is also a fourth, short head, which starts from the lateral condyle of the humerus through a round tendon (a mucous bursa is sometimes observed under it), most noticeable along the outer edge, and ends along the radial edge and the outer surface of the upper third of the ulna. At the top it borders with the lower edge of the inner head of the triceps extensor muscle of the shoulder, from which it is often difficult to separate it. This fourth head increases the surface of application of muscle force, bringing it closer to resistance and translates the resultant of the triceps extensor outward, which determines pure extension at the elbow joint.

The triceps extensor muscle of the shoulder with its long head can produce a corresponding movement in the shoulder joint (flexion back). With lower support, he moves the scapula, directing its upper inner corner upward and outward, and the lower one inward. In addition, it helps keep the surfaces of the shoulder joint in contact.

Innervation: radial nerve (n. radialis, CVI-VIII).

The elbow flexors, when working together, are able to exert greater force than the elbow extensors.*

* (R. Fick found that the ratio of the diameter of the elbow flexors to the diameter of the extensors in humans was 1:0.77; in a dog it is 1:2.85. The relatively larger diameter of the extensor muscle in the dog is explained by the position of the limb.

)

The force of gravity of the forearm plays a large part in extension; it is even known that with paralysis of the triceps extensor muscle, this movement is not destroyed. The triceps extensor does the most work when the arm is raised and bent at the elbow joint, since in this case it has to overcome the force of gravity of the forearm.

Symptoms

- Pain and tenderness on the inside of the elbow, especially when trying to throw a ball

- Clicking or cracking tear or discomfort during injury

- Swelling and hematomas (after 24 hours) at the site of injury on the inside of the forearm in the elbow area and above if a rupture has occurred.

- Inability to throw with full force, loss of ball control

- Stiffness in the elbow, inability to straighten the elbow

- Numbness or tingling in the fingers

- Impaired hand functions such as grasping and performing small movements.

Manifestations

In most cases, the clinical symptoms of medial epicondylitis develop gradually over a fairly long period of time. The most characteristic symptoms of this disease are the following:

- Pain localized on the inside of the lower part of the humerus. Initially, it appears after physical activity, and then can be at rest. Pain sensations vary in severity, depending on the intensity of the inflammatory reaction.

- Weakness of the forearm muscles, which perform the function of flexing the hand and fingers. This manifestation is a reaction of the muscle fibers of the striated skeletal muscles to the inflammatory response.

- Inflammatory manifestations of the tissues of the elbow joint area - they develop in the case of a pronounced pathological reaction, are characterized by redness (hyperemia) of the skin, as well as its swelling with an increase in tissue volume.

These manifestations bring discomfort to a person’s life, reduce his ability to work, and also eliminate the possibility of a future career for professional athletes.

Diagnostics

Pain over the medial aspect of the elbow, tenderness directly over the ulnar collateral ligament, and specific functional tests that simulate stress on the ligament may be helpful in diagnosing injury to this ligament. Specific physical tests include a valgus stress test, in which force is applied to the elbow and range of motion is tested. This may be the most sensitive functional test. MRI is the best method for imaging the soft tissues of the elbow joint. Small tears on the lower (deep part) of the ligament are especially well visualized when using contrast (injected into the elbow) as such damage cannot be seen without contrast.

Classification

Based on the localization of the pathological inflammatory process, medial and lateral epicondylitis is distinguished. According to the main causative factor, the disease can be of pathological and traumatic origin; usually the more common form of pathology is provoked by microtrauma of the forearm muscles and their tendons.

Also, for ease of diagnosis and choice of treatment, epicondylitis is classified into types according to the severity of the inflammatory process. All criteria for the classification of the disease are displayed in the final diagnosis after an objective diagnostic study.

Treatment

A minor injury may heal on its own.

Conservative treatment is indicated for most patients who manage to return to their usual activities. Conservative treatment includes: the use of NSAIDs (ibuprofen aspirin), analgesics, cold compresses on the injured area, limiting the load on the elbow, wearing a splint, and physical therapy. Surgical treatment is generally required only for a small number of patients with complete ligament rupture or those with persistent pain, hand dysfunction, or risk of ligament rupture. Most often, these patients are baseball players.

Operation Tommy John. Patients with an acute ligament tear, those who have failed conservative treatment, and those who wish to continue playing baseball require surgical reconstruction (repairing the ligament using other tissues). This operation is known as the "Tommy John" operation and is named after the player whose career was successfully saved when the ligament was reconstructed by Dr. Frank Jobe.

Ligament reconstruction can be performed using a variety of patient-derived soft tissue grafts, but is most often performed using the palmaris tendon of the forearm. This is explained by the fact that this tendon provides biomechanical characteristics that are similar to the native ligament, and since there are no consequences from its absence, it is an ideal replacement for the ligament. Some patients do not initially have a palmaris tendon and therefore require alternative grafts for reconstruction, such as leg extensor tendons.

How to determine the exact cause

When the arm does not fully extend, it makes sense to consult a doctor for an accurate diagnosis. Along the way, you need to try to remember the circumstances that accompanied the onset of the symptom - and be sure to tell the orthopedist about them at the first appointment.

The patient needs to remember whether he has suffered an injury in the last 2-3 days: perhaps his arm hurts and cannot be straightened precisely because of it. You also need to inform your doctor about previously diagnosed osteochondrosis, increased body temperature, and muscle myositis (if they have been diagnosed).

Complications of treatment

Possible complications of conservative treatment include:

- Inability to return to previous level of sports activities

- Frequent recurrence of symptoms such as inability to throw with full force or distance, pain when throwing, and loss of ball control, especially if sporting activity resumes soon after the injury

- Injury to other structures of the elbow, including the cartilage of the outer part of the elbow; decreased range of motion in the arm, ulnar nerve damage, medial epicondylitis, and sprained wrist flexor tendons.

- Damage to articular cartilage, resulting in the development of elbow arthritis

- Elbow stiffness (decreased range of motion)

- Symptoms of ulnar nerve neuropathy

Possible complications of surgical treatment include:

- Surgical complications not specifically related to this operation, such as pain, bleeding (rare), infections (

Complications characteristic of surgical treatment of this disease:

- Inability to restore normal stability

- Inability to return to previous activity level

- Ulnar nerve injuries

- Irritation of skin areas associated with palmaris tendon graft harvest

Criteria for evaluation

For elbow ligament injuries, three generally accepted methods are used to assess patient-reported outcomes:

- Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) is a 30-question questionnaire with a score ranging from 0 to 100, with 0 being no limitation. The DASH is well studied and valid with minimal clinically significant differences; either a 15-point clinically minimally important difference (MCID) scale or a 12.7-point minimally significant difference (MCD) scale.

- The Quick DASH test is usually used instead of DASH. The patient chooses the answer that is most characteristic of him (1-5 points for each question). Instructions for recording responses are listed below the questionnaire form, but Quick DASH does not have MCIDs studied like DASH does.

- The patient's personal functional scale is a scale in which the patient selects 5 tasks that are difficult to perform and evaluates these tasks from 0 to 10 points, where 0 is inability to perform and 10 is execution. The MCID for an average of 5 tasks is 2, while for one task the MCID is 3 points.