Ossification of the hip joints is a process of ossification that takes over 20 years. The formation of joint nuclei begins during the end of intrauterine development. At the same time, active ossification of the joints is observed. After birth, the newborn's bone tissue gradually matures and begins to resemble the bone of an adult. Absent or delayed ossification is a serious deviation, which, if not treated in a timely manner, leads to dysfunction of the musculoskeletal system.

Anatomical features

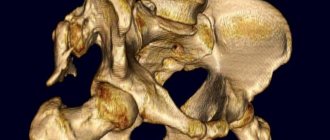

The formation of the hip joint in the fetus occurs in the middle of the period of intrauterine development. In the area of the head of the articulation, ossification nuclei are formed, the size of which at the time of birth of the child does not exceed 6 mm. The joint itself consists of cartilage tissue. During the first months of life, those parts of the joints that will be subject to physical stress are formed. If these structures do not ossify, the hip joints will not form properly, increasing the risk of dislocation.

If the formation of ossification centers occurs before six months of age, this option is considered normal. By older preschool age in children, these areas should increase on average 10 times compared to the period of infancy. A slow or completely absent process of ossification of the hip joint in a child is a reason for immediate correction of pathological processes.

Hip dysplasia in a child

If you still have questions, you can ask them using the Doctis service.

My daughter was diagnosed with hip dysplasia while still in the maternity hospital. What causes the disease?

Children whose parents had or have dysplasia or coxarthrosis of the hip joints are at risk. Other factors - the child was lying in a breech position, it was a large fetus, the baby had foot deformities, the mother had severe toxicosis during pregnancy or pathological reactions to the fetus (especially before 8-12 weeks of pregnancy), hormonal disorders during pregnancy.

In girls, hip dysplasia occurs 4-5 times more often than in boys. Hip dislocation often occurs in small children weighing less than 2500 g. Risks of dysplasia also include neuromuscular insufficiency of periarticular tissues (all muscles and intermuscular connective tissue formations around the joint).

My baby was prescribed orthopedic treatment in the very early months. It would be a sin to torture such a small creature. Is it really impossible to start treatment later?

Until one year of age, hip dysplasia is not considered a disease. But this condition necessarily requires adjustment and, if treatment is followed, it can easily go away for up to a year. After a year without adequate treatment, dysplasia progresses as the child grows and leads to serious joint problems. Therefore, during the first three months, babies must undergo an ultrasound of the hip joints. And after three months or in controversial cases, x-rays are prescribed for a more accurate diagnosis.

The positive effect of dysplasia treatment depends on both the methods and timing of treatment. Early treatment is one of the main principles. Almost all types of treatment (wide swaddling, special pillows and positioning, physiotherapy) are aimed at keeping the joints in a certain position and ensuring a certain function in movement. Massage and special therapeutic exercises are required both at the time of treatment and during rehabilitation and after removing special bandages.

I look at the neighbors’ children and the kids in the clinics. It seems that dysplasia is now being detected much more often.

This is wrong. It’s just that earlier doctors identified dysplasia as a separate disease and distinguished between subluxation, dislocation, and pre-luxation of the joint. Today, all of them have been combined into a single form - hip dysplasia, that is, a congenital inferiority of the joint, which manifests itself due to its improper development. Let's look at each condition separately.

- Pre-luxation is underdevelopment of the hip joint without displacement of the head of the femur relative to the acetabulum (the place where the femur enters - the glenoid cavity).

- Subluxation is underdevelopment of the hip joint with partial displacement of the femoral head relative to the acetabulum.

- Dislocation (or true dysplasia) is underdevelopment of the hip joint with complete displacement of the femoral head relative to the glenoid cavity.

- It is worth mentioning separately about the ossification nuclei. Quite often, underdevelopment of the nuclei of the femoral joint is combined with congenital dislocation of the hip. But these are far from the same thing and can be separate from each other. Anatomically, the hip joint begins to develop around the middle of pregnancy. Ossification nuclei are located in the region of the femoral head. At birth, the majority of the hip joints are made of cartilage. As they develop, ossification zones appear gradually. They become visible on x-rays by approximately 4-6 months of life, by 5-6 years these zones increase approximately 10 times (if this does not happen, then mandatory treatment is required, since this is already a serious developmental pathology), and complete their development by 20 years old. Underdevelopment of ossification nuclei plays, of course, an important role in hip dysplasia, which interferes with the full development of the joint.

Signs of hip dysplasia in newborns

The neonatologist in the maternity hospital folded the baby’s legs, bent them, spread them apart. And then he said: “dysplasia.” What did he see that I don’t see, fussing with the child every day?

In fact, you can see the problem yourself:

- one leg is shorter than the other;

- additional fold on the thigh;

- asymmetry of the gluteal folds and buttocks (this is a relative sign, and in itself does not always indicate the presence of dysplasia);

- limitation of hip abduction (but nevertheless, an ultrasound is required, since limitation in abduction can also be caused by muscle hypertonicity);

- at the moment of bending the legs in the knee and hip joints, a click occurs (it is determined by the doctor and is of particular importance in the first month of life).

But even if you find all the signs, this is not necessarily dysplasia. And vice versa: if you do not find a single sign, you need to see a doctor, because the process can be bilateral, which means it is very difficult for a non-professional to identify it.

Can a mother cure dysplasia herself? Teach how to do a massage correctly.

Massage plays a fairly important role, but you need to not just make a movement, but understand how all the structures of the joint are anatomically located, what is the force of pressure and the angle of rotation at the moment of movement. Therefore, trust the professionals in this matter. With the help of therapeutic massage, the specialist strengthens the muscles of the hip joint and forms the correct movements in it, completely restoring its volume. And don’t rush your baby’s development. Every motor skill has its time. For the first steps, a child with dysplasia must mature.

Causes of deviations in the development of ossification nuclei

The causes of lag in ossification of the hip joint of a child are conventionally divided into intrauterine and acquired after birth. Factors that occur during intrauterine development include:

- the impact of hidden infections on the formation of the fetus during pregnancy;

- hereditary predisposition to diseases of the musculoskeletal system;

- severe toxicosis;

- late pregnancy;

- breech presentation of the fetus.

After birth, delayed ossification of the joint is provoked by:

- endocrine diseases in a child;

- metabolic disorders;

- rickets.

A relationship has been established between deviations in the formation of the hip joint and artificial feeding of the child with formulas that do not contain enough vitamin D.

Classification according to ICD-10

ICD codes for pediatric hip dysplasia should be looked for in class Q65, congenital hip deformities. These include the following options: Q65.0. Congenital dislocation of the hip, unilateral Q65.1. Congenital dislocation of the hip, bilateral Q65.2. Congenital dislocation of the hip, unspecified Q65.3. Congenital subluxation of the hip, unilateral Q65.4. Congenital subluxation of the hip, bilateral Q65.5. Congenital subluxation of the hip, unspecified Q65.6. Unstable hip

- Predisposition to hip dislocation

- Predisposition to hip subluxation

Q65.8. Other congenital hip deformities

- Anterior displacement of the femoral neck

- Congenital acetabular dysplasia

- Congenital:

√ valgus position √ varus position

Q65.9. Congenital deformity of the hip, unspecified

Clinical manifestations

Deviation in the development of the hip joint leads to displacement of the head of the femur in a child under the age of one year. The reason for this phenomenon is the increased load on the joint. Pathology manifests itself:

- preluxation: asymmetry of the gluteal-femoral folds, increased muscle tone of the lower extremities and limited passive extension of the legs bent at the knees;

- subluxation: one limb is shorter than the other, and when the patient’s hips are spread apart, a click is heard, caused by the head slipping;

- dislocation: significantly limited mobility of the hips, the muscles of the limbs are very tense.

As children with delayed ossification of the hip learn to walk, they may notice unsteady gait and lameness.

Treatment of extraskeletal ossification

The main method is surgery.

Surgery is performed when the ossification is fully formed, that is, about a year after the injury. If you try to remove it earlier, complications and relapses occur. To decide on surgical treatment, a radiologist's opinion on the maturity of the ossification is required.

Indications for surgery:

- large ossification;

- compression of a nerve trunk or large vessel;

- significant limitation of movements;

- failure of conservative therapy.

Conservative treatment is used before and after surgery:

- NSAIDs;

- Corticosteroids;

- local radiotherapy.

Physiotherapy (heat therapy, electrophoresis, ultrasound) is used with caution, according to strict indications, as it can stimulate the growth of ossifications.

Motor rehabilitation is carried out with the development of joints. It is important to perform exercise therapy in any case. Dose the load very carefully. You cannot make sudden, sweeping movements, or overload. Damage to the ossification during exercise can lead to its growth and increased pain. Therefore, you should only exercise under the guidance of a doctor.

Prevention

Currently practically undeveloped. After operations and joint injuries, it is better to refrain from early massage, heat treatment, and intensive gymnastics.

Ossification of the hip and other joints is common and leads to limited movement and impaired self-care. The reasons and mechanism of their formation are not fully understood. Relapses often occur. But timely conservative and surgical treatment and persistent rehabilitation measures give good results.

Diagnostics

Absent or delayed ossification of the hip joint after six months of age requires timely and correct treatment. If you suspect this deviation, the child should be shown to a pediatric orthopedist.

Diagnostics include:

- study of visual symptoms present in the infant;

- Ultrasound of the hip joints;

- radiography in direct projection.

Based on the research, the child is given an accurate diagnosis and appropriate therapy is prescribed.

Treatment methods

Therapy for delayed ossification of the hip joint in a child is complex and includes measures that help correct the process of bone tissue formation.

Since in most cases problems with the formation of the musculoskeletal system in children under one year of age are associated with vitamin D deficiency, the child is prescribed antirachitic therapy. It includes taking the appropriate medication and organizing regular walks in the fresh air. If necessary, ultraviolet therapy is prescribed to compensate for the deficiency of vitamin D in the body.

Volkov splint for hip dysplasia

A small patient may be prescribed an orthopedic splint, the design of which ensures the correct location of the joint structures, which will contribute to their healthy formation.

Physiotherapy is an effective measure that normalizes the ossification process:

- paraffin therapy - impact on the problematic part of the musculoskeletal system;

- electrophoresis of the lumbar spine using the drug Eufilina;

- electrophoresis using a combination of bischofite and phosphorus;

- warm baths with sea salt.

Therapeutic exercise and massage are mandatory components of complex therapy. Exercise therapy in combination with massage is performed under the supervision of an experienced pediatric massage therapist-rehabilitator. Exercise therapy includes exercises for spreading the legs bent at the knees, pulling the bent knees towards the stomach, pushing the feet away from the support. All exercises are performed in a lying position.

Massage involves a delicate effect on the muscles of the hip area.

While the small patient is undergoing treatment, any stress associated with walking, sitting and standing is excluded. Violation of this rule will lead to ineffective therapy. To prevent the baby from making sudden movements, it must be constantly monitored.

After completing the therapeutic course, the patient is shown a control ultrasound examination, which helps to evaluate the effectiveness of the measures taken.

Absent ossification is a deviation that requires a more serious approach to the treatment of children. If the ossification process does not develop, prosthetic replacement of the affected hip joint is indicated.

Conclusion

Hip dysplasia in children is a common pathology, but in the vast majority of cases it resolves on its own and does not require special medical intervention. In more complex cases, it may be necessary to wear various fixation devices for several weeks - until normal formation of the joint is completed - without requiring either casting or "strict" swaddling. In isolated cases, surgery may be required, and the earlier it is performed, the higher the chances of success. References

1. Wedge JH, Wasylenko MJ. The natural history of congenital dislocation of the hip: a critical review // Clin Orthop Relat Res 1978; :154. 2. Wedge JH, Wasylenko MJ. The natural history of congenital disease of the hip // J Bone Joint Surg Br 1979; 61-B:334. 3. Crawford AH, Mehlman CT, Slovek RW. The fate of untreated developmental dislocation of the hip: long-term follow-up of eleven patients // J Pediatr Orthop 1999; 19:641. 4. Bialik V, Bialik GM, Blazer S, et al. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: a new approach to incidence // Pediatrics 1999; 103:93. 5. Castelein RM, Sauter AJ. Ultrasound screening for congenital dysplasia of the hip in newborns: its value // J Pediatr Orthop 1988; 8:666. 6. Terjesen T, Holen KJ, Tegnander A. Hip abnormalities detected by ultrasound in clinically normal newborn infants // J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996; 78:636. 7. Marks DS, Clegg J, al-Chalabi AN. Routine ultrasound screening for neonatal hip instability. Can it abolish late-presenting congenital dislocation of the hip? // J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994; 76:534. 8. Dezateux C, Rosendahl K. Developmental dysplasia of the hip // Lancet 2007; 369:1541. 9. Harris NH, Lloyd-Roberts GC, Gallien R. Acetabular development in congenital dislocation of the hip. With special reference to the indications for acetabuloplasty and pelvic or femoral realignment osteotomy // J Bone Joint Surg Br 1975; 57:46. 10. Schwend RM, Pratt WB, Fultz J. Untreated acetabular dysplasia of the hip in the Navajo. A 34 year case series followup // Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999; :108. 11. Wood MK, Conboy V, Benson MK. Does early treatment by abduction splintage improve the development of dysplastic but stable neonatal hips? // J Pediatr Orthop 2000; 20:302. 12. Shaw BA, Segal LS, SECTION ON ORTHOPAEDICS. Evaluation and Referral for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Infants // Pediatrics 2016; 138. 13. Murphy SB, Ganz R, Müller ME. The prognosis in untreated dysplasia of the hip. A study of radiographic factors that predict the outcome // J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995; 77:985. 14. Terjesen T. Residual hip dysplasia as a risk factor for osteoarthritis in 45 years follow-up of late-detected hip dislocation // J Child Orthop 2011; 5:425. 15. Lindstrom JR, Ponseti IV, Wenger DR. Acetabulular development after reduction in congenital dislocation of the hip // J Bone Joint Surg Am 1979; 61:112. 16. Cherney DL, Westin GW. Acetabular development in the infant's dislocated hips // Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989; :98. 17. Brougham DI, Broughton NS, Cole WG, Menelaus MB. The predictability of acetabular development after closed reduction for congenital dislocation of the hip // J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988; 70:733. 18. Albinana J, Dolan LA, Spratt KF, et al. Acetabular dysplasia after treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Implications for secondary procedures // J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004; 86:876. 19. Weinstein SL, Mubarak SJ, Wenger DR. Developmental hip dysplasia and dislocation: Part II // Instr Course Lect 2004; 53:531. 20. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: recommendation statement // Pediatrics 2006; 117:898. 21. Lorente Moltó FJ, Gregori AM, Casas LM, Perales VM. Three-year prospective study of developmental dysplasia of the hip at birth: should all dislocated or dislocatable hips be treated? // J Pediatr Orthop 2002; 22:613. 22. Larson JE, Patel AR, Weatherford B, Janicki JA. Timing of Pavlik harness initiation: Can we wait? // J Pediatr Orthop 2021. 23. Flores E, Kim HK, Beckwith T, et al. Pavlik harness treatment may not be necessary for all newborns with ultrasonic hip dysplasia // J Pediatr Health Care 2016; 30:304. 24. Rosendahl K, Dezateux C, Fosse KR, et al. Immediate treatment versus sonographic surveillance for mild hip dysplasia in newborns // Pediatrics 2010; 125:e9. 25. Burger BJ, Burger JD, Bos CF, et al. Frejka pillow and Becker device for congenital dislocation of the hip. Prospective 6-year study of 104 late-diagnosed cases // Acta Orthop Scand 1993; 64:305. 26. Atar D, Lehman WB, Tenenbaum Y, Grant AD. Pavlik harness versus Frejka splint in treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip: bicenter study // J Pediatr Orthop 1993; 13:311. 27. Danielsson L, Hansson G, Landin L. Good results after treatment with the Frejka pillow for hip dysplasia in newborn infants: a 3-year to 6-year follow-up study // J Pediatr Orthop B 2005; 14:228. 28. Czubak J, Piontek T, Niciejewski K, et al. Retrospective analysis of the non-surgical treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip using Pavlik harness and Frejka pillow: comparison of both methods // Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 2004; 6:9. 29. Carmichael KD, Longo A, Yngve D, et al. The use of ultrasound to determine timing of Pavlik harness discontinuation in treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip // Orthopedics 2008; 31. 30. Tiruveedhula M, Reading IC, Clarke NM. Failed Pavlik harness treatment for DDH as a risk factor for avascular necrosis // J Pediatr Orthop 2015; 35:140. 31. Hedequist D, Kasser J, Emans J. Use of an abduction brace for developmental dysplasia of the hip after failure of Pavlik harness use // J Pediatr Orthop 2003; 23:175. 32. Cashman JP, Round J, Taylor G, Clarke NM. The natural history of developmental dysplasia of the hip after early supervised treatment in the Pavlik harness. A prospective, longitudinal follow-up // J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84:418. 33. Nakamura J, Kamegaya M, Saisu T, et al. Treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip using the Pavlik harness: long-term results // J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007; 89:230. 34. Walton MJ, Isaacson Z, McMillan D, et al. The success of management with the Pavlik harness for developmental dysplasia of the hip using a United Kingdom screening program and ultrasound-guided supervision // J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92:1013. 35. Lerman JA, Emans JB, Millis MB, et al. Early failure of Pavlik harness treatment for developmental hip dysplasia: clinical and ultrasound predictors // J Pediatr Orthop 2001; 21:348. 36. Kitoh H, Kawasumi M, Ishiguro N. Predictive factors for unsuccessful treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip by the Pavlik harness // J Pediatr Orthop 2009; 29:552. 37. Ömeroğlu H, Köse N, Akceylan A. Success of Pavlik Harness Treatment Decreases in Patients ≥ 4 Months and in Ultrasonographically Dislocated Hips in Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip // Clin Orthop Relat Res 2016; 474:1146. 38. Eidelman M, Katzman A, Freiman S, et al. Treatment of true developmental dysplasia of the hip using Pavlik's method // J Pediatr Orthop B 2003; 12:253. 39. Bialik GM, Eidelman M, Katzman A, Peled E. Treatment duration of developmental dysplasia of the hip: age and sonography // J Pediatr Orthop B 2009; 18:308. 40. Murnaghan ML, Browne RH, Sucato DJ, Birch J. Femoral nerve palsy in Pavlik harness treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip // J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93:493. 41. Hart ES, Albright MB, Rebello GN, Grottkau BE. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: nursing implications and anticipatory guidance for parents // Orthop Nurs 2006; 25:100. 42. Hassan FA. Compliance of parents with regard to Pavlik harness treatment in developmental dysplasia of the hip // J Pediatr Orthop B 2009; 18:111. 43. Kosar P, Ergun E, Gökharman FD, et al. Follow-up sonographic results for Graf type 2A hips: association with risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip and instability // J Ultrasound Med 2011; 30:677. 44. Luhmann SJ, Bassett GS, Gordon JE, et al. Reduction of a dislocation of the hip due to developmental dysplasia. Implications for the need for future surgery // J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85-A:239. 45. Holman J, Carroll KL, Murray KA, et al. Long-term follow-up of open reduction surgery for developmental dislocation of the hip // J Pediatr Orthop 2012; 32:121. 46. Rampal V, Sabourin M, Erdeneshoo E, et al. Closed reduction with traction for developmental dysplasia of the hip in children aged between one and five years // J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90:858. 47. Carney BT, Clark D, Minter CL. Is the absence of the ossific nucleus prognostic for avascular necrosis after closed reduction of developmental dysplasia of the hip? // J Surg Orthop Adv 2004; 13:24. 48. Segal LS, Boal DK, Borthwick L, et al. Avascular necrosis after treatment of DDH: the protective influence of the ossific nucleus // J Pediatr Orthop 1999; 19:177. 49. Chen C, Doyle S, Green D, et al. Presence of the Ossific Nucleus and Risk of Osteonecrosis in the Treatment of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort and Case-Control Studies // J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017; 99:760. 50. Gould SW, Grissom LE, Niedzielski A, et al. Protocol for MRI of the hips after spica cast placement // J Pediatr Orthop 2012; 32:504. 51. Desai AA, Martus JE, Schoenecker J, Kan JH. Spica MRI after closed reduction for developmental dysplasia of the hip // Pediatr Radiol 2011; 41:525. 52. Tiderius C, Jaramillo D, Connolly S, et al. Post-closed reduction perfusion magnetic resonance imaging as a predictor of avascular necrosis in developmental hip dysplasia: a preliminary report // J Pediatr Orthop 2009; 29:14. 53. Aksoy MC, Ozkoç G, Alanay A, et al. Treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip before walking: results of closed reduction and immobilization in hip spica cast // Turk J Pediatr 2002; 44:122. 54. Murray T, Cooperman DR, Thompson GH, Ballock T. Closed reduction for treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip in children // Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2007; 36:82. 55. Senaran H, Bowen JR, Harcke HT. Avascular necrosis rate in early reduction after failed Pavlik harness treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip // J Pediatr Orthop 2007; 27:192. 56. Moseley CF. Developmental hip dysplasia and dislocation: management of the older child // Instr Course Lect 2001; 50:547. 57. Gans I, Flynn JM, Sankar WN. Abduction bracing for residual acetabular dysplasia in infantile DDH // J Pediatr Orthop 2013; 33:714. 58. Sewell MD, Rosendahl K, Eastwood DM. Developmental dysplasia of the hip // BMJ 2009; 339:b4454. 59. Kamath SU, Bennet GC. Re-dislocation following open reduction for developmental dysplasia of the hip // Int Orthop 2005; 29:191. 60. Wada A, Fujii T, Takamura K, et al. Pemberton osteotomy for developmental dysplasia of the hip in older children // J Pediatr Orthop 2003; 23:508. 61. Ertürk C, Altay MA, Yarimpapuç R, et al. One-stage treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip in untreated children from two to five years old. A comparative study // Acta Orthop Belg 2011; 77:464. 62. Subasi M, Arslan H, Cebesoy O, et al. Outcome in unilateral or bilateral DDH treated with one-stage combined procedure // Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466:830. 63. Sarkissian EJ, Sankar WN, Zhu X, et al. Radiographic Follow-up of DDH in Infants: Are X-rays Necessary After a Normalized Ultrasound? // J Pediatr Orthop 2015; 35:551. 64. Engesaeter IØ, Lie SA, Lehmann TG, et al. Neonatal hip instability and risk of total hip replacement in young adulthood: follow-up of 2,218,596 newborns from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register // Acta Orthop 2008; 79:321. 65. Carroll KL, Schiffern AN, Murray KA, et al. The Occurrence of Occult Acetabular Dysplasia in Relatives of Individuals With Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip // J Pediatr Orthop 2016; 36:96.