With severe arthrosis of the hip joint, conservative treatment does not give the desired result. The only way to relieve a patient of pain and return him to normal physical activity is hip replacement surgery.

As with any other surgical procedure, complications can develop after hip replacement. Their occurrence is influenced by the patient’s age, the nature of the pathology in the joint, concomitant diseases, and excess weight. Therefore, before the operation begins, all possible reasons are taken into account to minimize the risk of complications in the postoperative period.

Postoperative pain

In the first month after hip replacement, the patient may experience pain and discomfort. They can be concentrated in the area of the surgical wound, spreading to the knee and groin. Such pain is considered a natural response of the body to surgical trauma (skin incision, muscle dissection). To relieve them, the patient is prescribed painkillers.

Patients may often experience lower back pain after hip replacement surgery. Typically, such pain occurs during physical activity. This is associated with an exacerbation of osteochondrosis due to the restoration of the length of a previously shortened limb and an increase in the load on the spine. With proper rehabilitation measures, back pain after hip replacement goes away over time.

Indications and contraindications for surgery

In order for the operation to replace the hip joint to be high-quality and without negative consequences, the surgeon determines the absence of contraindications and the presence of indications for endoprosthetics in the patient. Surgical intervention is not required for every pathology and diagnosis. Doctors often resort to conservative therapy if possible. In addition, endoprosthetics is a rather complex and expensive operation that requires preparation from the surgeon and the patient.

Main indications for hip replacement:

- the hip joint hurts due to aseptic necrosis of the head of the joint;

- the presence of comminuted fractures in the hip bone;

- new fractures and injuries in the femoral neck in patients aged 65+;

- tumors in the neck or head of the femur;

- osteoarthritis of the joints, 3rd or 4th degree of the disease;

- false joints or non-union fractures in the hip bone;

- damage and destruction of joints due to connective tissue diseases: rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, ankylosing spondylitis.

The operation also has certain contraindications:

- Psychoneurological diseases.

- Pathologies of the cardiovascular system.

- Tuberculosis.

- Osteomyelitis in acute or chronic form.

Postoperative complications

Despite all the measures taken to prevent complications, there is still a risk of their occurrence. They can develop due to incomplete preoperative examination of the patient or errors by the operating doctor. However, more often, improper postoperative care and non-compliance with the physical activity regimen outside the hospital are to blame for the occurrence of complications.

One of the most common complications is dislocation of the implant head. It is characterized by pain that intensifies with movement, muscle spasm around the hip joint, and forced positioning of the operated leg. Characteristic symptoms of this complication after hip replacement are lameness and shortening of the affected limb.

In the presence of an untreated chronic inflammatory process in the patient’s body, there is a possibility of developing paraprosthetic infection in the tissues surrounding the endoprosthesis. In the future, it can lead to the formation of a purulent fistula and the development of osteomyelitis. The inflammatory process is characterized by severe pain, swelling and redness in the area of the operated joint. The skin becomes hot to the touch, and the patient develops a fever.

Severe complications include periprosthetic fracture of the femur. It is characterized by acute, sharp pain, rapidly increasing swelling, redness, crunching when moving and palpating the operated area, deformation of the leg and the impossibility of active movements.

During the operation, there is a risk of damage to the fibular nerve, resulting in the development of neuropathy. It is characterized by intermittent pain of various localizations, weakness of the ankle joint, and a feeling of numbness in the toes and feet.

The most dangerous complication is pulmonary embolism, when a blood clot that breaks off during surgery clogs its lumen. The patient suddenly develops shortness of breath, weakness, and suffocation. The patient loses consciousness. If urgent resuscitation measures are not provided, death occurs. This complication is quite rare.

Why do you need a hip replacement?

One of the largest joints in the human body is the hip joint . When carrying out daily operations, considerable loads are placed on it. The reason for this is the connection of the lower extremities with the pelvic part.

The tendons and muscles in the hip joint contract, due to which the movement is performed. A healthy joint allows movement in any direction and plane due to its mobility. This range of movements provides several functions that are important for the human body:

- walking and running;

- support;

- jumping;

- performing strength exercises and cardio exercises.

To undergo replacement , certain indications are needed. These may include severe pain in the hip joint area, destruction of the tissue structure or joint components, and the inability to perform simple movements of the limbs. That is, the only indication for replacing the hip joint with an artificial prosthesis is a situation where it does not fulfill its physiological function (and also worsens the patient’s quality of life and well-being). Then it is surgical intervention that helps solve the problem.

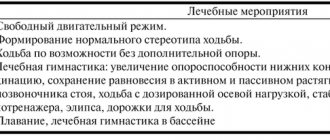

Rehabilitation after hip replacement

When a hip replacement has already been performed, rehabilitation first begins in the intensive care unit. The patient is under medical supervision until the anesthesia wears off. Only then can he be transferred to the ward. A few hours later, the patient is helped to get out of bed and sit in a chair. He will be able to feel stable on his own approximately 1-2 days after the operation. At this time, you can walk with support. During rehabilitation, the patient must take painkillers and anti-inflammatory drugs prescribed by the doctor.

After the replacement of the hip joint is completed, rehabilitation lasts from one week to ten days. The main goal of such rehabilitation is to prevent complications after surgery. Also, medical care and examination are needed to improve the mobility of the installed prosthesis.

In addition, in the first weeks after endoprosthetics, doctors will involve the patient in light physical therapy exercises. At the same time, the patient takes painkillers and antibiotics. With the correct rehabilitation period, the patient can easily complete the entire rehabilitation after hip replacement - 3-6 months. During this time, he will learn, with the help of an instructor, to tense the muscles in the ankles and hips. It is these exercises that help improve blood flow to the muscles, prevent swelling and the formation of blood clots. But it is important that they are carried out under the supervision of an experienced instructor-methodologist of the exercise therapy program.

POLYTRAUMA / POLYTRAUMA

Egiazaryan K.A., Sirotin I.V., Ratyev A.P., Korobushkin G.V., Lazishvili G.D., But-Gusaim A.B.

Russian National Research Medical University named after N.I. Pirogov, Moscow, Russia

ASEPTICA LYMPHOREA AFTER HIP ENDOPROSTHETICS

One of the complications after hip replacement is prolonged non-healing of the wound with continued discharge. Often, when such a situation is identified, surgeons take intervention measures that in some cases have directly opposite directions - from conservative wound management to aggressive surgical tactics with revision of the installed joint up to the replacement of its components. This difference in approaches is associated with an insufficiently developed algorithm of action in the presence of prolonged non-healing of a wound without obvious signs of infection. There is an opinion that in some cases the cause of this situation is damage to the lymphatic vessels and nodes during surgery with the occurrence of lymphorrhea. At the same time, in the specialized traumatology and orthopedic literature, we were unable to find works devoted to the tactics of managing such patients, not only during hip replacement, but also during other types of specialized operations. In addition, even mention of lymphorrhea as a separate specific complication is given only in a limited number of publications. However, in percentage terms, lymphorrhea after hip replacement is not so rare. Thus, Tkachenko et al. [1] report lymphorrhea as a complication of this type of surgery in 0.5% of cases. In addition, Mayer et al. notes that among all cases of lymphorrhea, more than 17% occur after hip arthroplasty [2]. However, in many studies, prolonged discharge from a postoperative wound is often associated with an infectious process [3]. In this article, we tried to summarize information about the phenomenon of lymphorrhea and possible tactics for managing such patients in the event of the development of a similar complication as a result of hip arthroplasty.

Terminology and anatomical background

Lymphorrhea (lymphorrhoea; Lymph + Greek rhoia flow, outflow; synonym of lymphorrhagia lymphorrhagia; Lymph + Greek rhagos ruptured, torn) outflow of lymph onto the surface or in the body cavity due to damage or disease of the lymphatic vessels [4]. As a complication of surgical interventions, lymphorrhea is quite common in the practice of surgeons. Lymphorrhea due to damage to the inguinal lymph nodes often occurs after removal of veins, as well as radical lymphadenectomy for oncological lesions in this area (Ducuing and Shkolnik operations). A feature of these surgical interventions is partial unintentional damage or subtotal removal of lymph nodes and lymphatic ducts from the femoral triangle. The femoral triangle is a topographic formation bounded above (base of the triangle) by the inguinal ligament lig. inguinale, externally by the sartorius muscle m. sartorius, from the inside by the long adductor m. adductor longus. The bottom of the triangle, called the iliopectineal fossa fossa iliopectinea, is formed by the iliopsoas and pectineus muscles mm. iliopsoas et pectineus [5]. In this area there is a group of lymphatic ducts that form the anteromedial lymphatic collector, as well as a group of superficial and deep lymph nodes. The latter are located under the lata fascia of the thigh directly on mm. iliopsoas et pectineus, and the lymphatic vessels flowing into them go far into the region of the gluteal muscles. The ratio of complications from the postoperative wound when performing angiosurgical interventions in this area is interesting. Thus, according to Shevchenko, about 90% (!) of complications after phlebectomy are lymphohematomas [6]. Of course, returning to endoprosthetics, we can confidently note that such operations are performed in a slightly different anatomical zone. This can explain the significantly lower frequency of such complications during hip replacement, however, without excluding the possibility of damage to the deep inguinal lymph nodes and vessels located directly on the m. iliopsoas. During access to the acetabulum, its exposure, excision or dissection of the joint capsule, removal of central and anterior osteophytes in arthrosis, this muscle is visualized in the wound, which means it can be damaged, as well as other anatomical structures located in close proximity to it. In a study by Malinin et al. Contrast lymphography was performed in the thigh and groin area [7]. The figure shows the location of the anteromedial lymphatic collector, consisting of 14-16 lymphatic vessels, sequentially flowing into the inguinal lymph nodes. Noteworthy is the location of a significant part of these vessels very close to the acetabulum, which again allows for the theoretical possibility of their damage (Fig.).

Drawing. Direct contrast lymphorrhea through the left lower limb: left inguinal and iliac regions, the anteromedial lymphatic collector is represented by 14-16 lymphatic vessels, sequentially flowing into the inguinal lymph nodes (according to A.A. Malinich, S.I. Pryadko, M.S. Dzhabaeva. Diagnosis and treatment of hemochyloperitoneum in chylous malforations with gravitational reflux of chyle into the visceral organs)

Diagnostics

Difficulties in the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of lymphorrhea are associated primarily with the fact that, according to current ideas in operative orthopedics, most problems with non-healing of wounds and long-term preservation of wound discharge are considered a manifestation of the development of an infectious process. Thus, Zimmerli et al. define prolonged wound discharge as a suspicion of infection, for which it is recommended to perform a revision of the postoperative wound no later than 3 weeks from the onset of symptoms [8]. This approach is absolutely justified if an infectious genesis of the complication is suspected. But if we accept the assumption that the nature of the discharge is aseptic lymphorrhea, - according to a number of researchers - we should start with conservative measures [9]. This approach is attractive because it reduces the overall cost of treating the patient and the risk of repeated surgery. The clinical picture of lymphorrhea with damage to the anteromedial collector has been described in detail in various studies on complications after removal of veins for varicose veins of the lower extremities, and removal of inguinal lymph nodes during oncological operations. In typical cases, lymphorrhea begins in the area of the postoperative wound on the 4-7th day after surgery, and is characterized by the separation of light liquid with a possible pink tint due to the admixture of red blood cells. The discharge may be constant or periodic at various intervals. This is due to the formation of a “false lymphocell” – a cavity filled with lymph. Lymphatic infiltrates are also formed—impregnation of soft tissues with lymph, their compaction and tension of the skin [10]. In the early stages of lymphorrhea, an important point in diagnosis is confirmation of the origin of the exudate and differential diagnosis with a lysed hematoma. In terms of the chemical and cellular composition, peripheral lymph in the lymphatic vessels of the extremities (the composition of lymph, unlike plasma, is not always homogeneous and can differ significantly depending on the level of the lymphatic vessel) differs significantly from plasma. However, in the literature available to us there is no consensus regarding its qualitative composition [11-14]. Apparently, this is due to the high variability of lymph composition in normal and pathological conditions. However, in all studies, lymph is a transparent light yellow liquid, less dense and with at least two times less protein relative to the composition of plasma. The cellular composition is represented predominantly by white blood cells in quantities from 500 to 75,000 per ml. These features can help in making a differential diagnosis between the separation of lymph during lymphorrhea and plasma during discharge of a lysed hematoma. Considering the possibility of the formation of cavities filled with lymph, ultrasound is important to determine the size of the cavity, the nature of its contents and the possibility of performing a puncture under ultrasound control with subsequent analysis of the exudate. With lymphorrhea and “false lymphocell,” the cellular and chemical composition will correspond to the structure of the lymph, and bacteriological culture will be negative [15-17]. Also, to clarify the diagnosis, it is possible to use magnetic resonance imaging, which will not only help to accurately determine the location and volume of the cavity, but will also determine the nature of the exudate - serous, hemorrhagic or purulent [18, 19].

Prevention and treatment

Unlike lymphorrhea, which occurs after phlebectomies in the distal parts of the limb and self-limited within 10-15 days, lymphorrhea when the structures of the anteromedial lymphatic collector are damaged without adequate therapy is prone to a long course, the formation of a “true lymphocell” (a cavity of “false lymphocell” overgrown with a fibrous capsule, which prevents its collapse and overgrowth) and lymphatic fistulas [10]. These complications can lead to the development of secondary wound infection [20] and, as a consequence, to the development of periprosthetic infection. When performing surgical operations that are traditionally accompanied by lymphorrhea in the postoperative period, various methods of prevention are used. These measures are especially appropriate in patients with high plasma levels of interleukin-1. Such patients are more prone to seroma formation [21]. Preoperative administration of methylprednisolone may be beneficial for reducing the volume of postoperative lymphorrhea [22]. Agrawal recommends the use of an ultrasonic scalpel instead of a traditional electric cautery for the prevention of lymphorrhea [23]. The local use of thrombin, as well as fibrin and thrombin glues, receives positive feedback from researchers [24, 25]. Oertli's work showed that the use of tranexamic acid, in addition to reducing blood loss, reduces the amount of postoperative lymphorrhea [26]. The nutritional status of the patient may also be important from the point of view of the development of this complication - a reduced plasma protein content contributes to the development of lymphorrhea [21]. In the absence of reliable signs of infection, treatment of lymphorrhea traditionally begins with conservative measures using elastic compression and pressure bandages [9]. For the treatment of lymphorrhea that occurs after general surgical interventions, the use of UHF is also recommended, which is doubtful in the case of lymphorrhea after endoprosthetics due to the presence of a metal implant. A low-fat diet is prescribed [27]. Popular methods for the ineffectiveness of elastic compression are puncture of the lymphocell under ultrasound control followed by the application of pressure bandages, administration of local drugs through lymphatic fistulas, for example, Levomikol ointment, 1% iodine solution, which has a sclerosing effect [10], as well as the drug 5- fluorouracil [28]. One of the effective methods in the treatment of lymphorrhea is the use of radiation therapy. Mayer reports the effective use of low doses of radiation from 0.3 to 0.5 Gy for the relief of lymphorrhea [2]. The use of radiation therapy is not recommended for more than 3 weeks if there is no effect [20]. The use of VAC therapy may also be effective in closing lymphatic fistulas. The appropriate duration of vacuuming, according to Abai, is 14 days [29]. However, to achieve optimal effect, some authors recommend long-term use of vacuum therapy - from 4 weeks to 2 months [30]. If conservative measures are ineffective, surgical intervention must be performed. Of the variety of surgical interventions for inguinal lymphorrhea, we note only those that, in our opinion, are possible and appropriate with a hip joint endoprosthesis installed. To perform suturing of lymphatic vessels, it is recommended to carry out revision of the postoperative wound and ligation of damaged lymphatic vessels found in the wound. To visualize them, a vital dye (Evans blue or indigo carmine) is injected into the skin of the first interdigital space 1 hour before surgery [9]. It is possible to use the Vvedensky method, when the lymphatic vessels are ligated at the level of the medial femoral condyle, where they are located in the projection of the great saphenous vein [31]. Methylene blue and indocyan green are also recommended for use as dyes [32]. As a visualization method before the next surgical option - microsurgical creation of a lymphovenous anastomosis - along with staining, it is advisable to use magnetic resonance lymphangiography, which allows you to accurately determine the location of the damage [33]. Here we would like to note that, in our opinion, techniques for visualizing lymphatic vessels associated with their staining by introducing dyes into the distal parts of the lymphatic vessels may not be fully relevant for lymphorrhea after hip replacement. This is due to the fact that damage to the lymphatic collectors that carry lymph to the inguinal lymph nodes from more cephalad areas cannot be completely ruled out.

CONCLUSION

In our opinion, the problem of lymphorrhea after hip replacement deserves close attention. In many ways, prolonged non-healing of the wound may be associated with the development of this complication, and overly aggressive surgical tactics aimed at sanitation of the wound can, on the contrary, only provoke increased lymphorrhea. However, indecisiveness in performing early revision of a postoperative wound in case of suspected infection can lead to aggravation of the situation and loss of the endoprosthesis. Therefore, it seems to us, an important step is to develop clear criteria not only for determining the septic process in a wound, but also for confirming its aseptic course.

Funding and conflict of interest information:

The study had no sponsorship. The authors declare that there are no obvious or potential conflicts of interest related to the publication of this article.

LITERATURE:

1. Tkachenko AN, Tkachenko AN, Lapshinov EB et al. Features of hip joint replacement in adult patients. Fundamental Researches. 2011; (10): 162-165. Russian (Tkachenko A.N., Tkachenko A.N., Lapshinov E.B., et al. Features of hip replacement in patients of older age groups // Fundamental Research. 2011. No. 10. P. 162-165) 2. Mayer R, Sminia P, McBride WH et al. Lymphatic fistulas: obliteration by low-dose radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005; 181(10): 660-664 3. Vinkler T, Trampush A, Rents N, Perka K, Bozhkova SA. Classification and the treatment and diagnostic algorithm for hip joint periprosthetic infection. Traumatology and Orthopedics of Russia. 2016; 1(79): 33-45. Russian (Winkler T., Trampush A., Renz N., Perka K., Bozhkova S.A. Classification and algorithm for diagnosis and treatment of periprosthetic infection of the hip joint // Traumatology and Orthopedics of Russia. 2021. No. 1(79). P. 33-45) 4. Small medical encyclopedia. M.: Medical Encyclopedia 1991-1996. Russian (Small Medical Encyclopedia. M.: Medical Encyclopedia. 1991-1996) 5. Prives MG, Lysenkov NK, Bushkovich VI. Human Anatomy. M.: Hippocrates, 1998. 704 p. Russian (Growth M.G., Lysenkov N.K., Bushkovich V.I. Human Anatomy. M.: Hippocrates, 1998. 704 pp.) 6. Errors, hazards and complications in venous surgery: the manual for physicians / edited by Shevchenko YuL. St. Petersburg: PiterCom, 1999. 320 p. Russian (Errors, dangers and complications in vein surgery: a guide for doctors / edited by Yu.L. Shevchenko. St. Petersburg: PiterKom, 1999. 320 pp.) 7. Malinin AA, Pryadko SI, Dzhadaeva MS. Diagnosis and treatment of hemochyloperitoneum in chylous malformations with gravitation reflux of chyle into visceral organs // Herald of Lymphology. 2014; (1): 29-34. Russian (Malinin A.A., Pryadko S.I., Dzhabaeva M.S. Diagnosis and treatment of hemochyloperitoneum in chylous malforations with gravitational reflux of chyle into the visceral organs // Bulletin of Lymphology. 2014. No. 1. P. 29-34) 8 Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med. 2004; 351(16): 1645-1654 9. Sushkov SA. Complications of surgical treatment of varicose disease of lower extremities. News of Surgery. 2008; 1 (16): 140-151. Russian (Sushkov S.A. Complications during surgical treatment of varicose veins of the lower extremities // News of surgery. 2008. No. 1(16). P. 140-151) 10. Albamasov KG, Malinin AA. Pathogenesis and management of lymphorrhea and lymphocele after vascular surgery of lower extremities. Surgery. 2004; (3): 23-30. Russian (Albamasov K.G., Malinin A.A. Pathogenesis and tactics of treatment of lymphorrhea and lymphocele after vascular operations on the lower extremities // Surgery. 2004. No. 3. P. 23-30) 11. Zhdanov DA. General anatomy and physiology of lymphatic system. Leningrad: Medgiz. Leningrad department, 1952. 336 p. Russian (Zhdanov D.A. General anatomy and physiology of the lymphatic system. Leningrad: Medgiz. Leningrad department, 1952. 336 pp.) 12. Rusznyák İ, Földi M, Szabó G. Lymphatics and Lymph Circulation, 2nd ed. Oxford, 1967 13. Pérez-de la Fuente T, Sandoval E, Alonso-Burgos A, García-Pardo L, Cárcamo C, Caballero O. Knee Lymphocutaneous Fistula Secondary to Knee Arthroplasty. Case Reports in Orthopedics. Volume 2014, Article ID 806164, 4 pages. URL: https://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/806164 14. Zavarzin AA, Rumyantsev AA. Course of histology. M., 1946. P. 421-424. Russian (Zavarzin A.A., Rumyantsev A.A. Course of histology. M., 1946. P. 421-424) 15. Korneev KV. Modern directions of prevention of lymphorrhea in patients with breast cancer after radical mastectomy (literature review). Herald of Russian Scientific Center of X-ray Radiology. 2012. Mode of approach: https://vestnik.rncrr.ru/vestnik/v12/papers/korneev_v12.htm Russian (Korneev K.V. Modern directions for the prevention of lymphorrhea in patients with breast cancer after radical mastectomies (literature review) // Bulletin of the Russian Research Center for Reconstruction and Research of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, 2012. Access mode: https://vestnik.rncrr.ru/vestnik/v12/papers/korneev_v12.htm) 16. Cihangir Ozaslan, Kerim Bora Yilmaz et al. Effect of mechanical closure of dead space on seroma formation in modified radical mastectomy. Turk j of med Sci. 2010; 40(5): 751-755 17. Katsuma Kuroi, Kojiro Shimozuma, Tetsuya Tagichi et al. Pathophysiology of seroma in breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2005; 12(4): 34-39 18. Mazzocchi M, Dessy LA, Corrias F. A clinical study of late seroma in breast implantation surgery. Aesthetic and Plastic Surgery. 2011; 34: 53-60 19. Oliveira VM, Junior DR, Lucas F, Lucarelli A. Late seroma after breast augmentation with silicone prostheses: a case report. The Breast Journal. 2007; 12(3): 421-423 20. Konstantinova GD, Zubarev AR, Gradusov EG. Phlebology. M.: Vidar, 2000. 160 p. Russian (Konstantinova G.D., Zubarev A.R., Gradusov E.G. Phlebology. M.: Vidar, 2000. 160 p.) 1. Klink CD, Binnebosel M, Lucas AH, et al. Serum analyzes for protein, albumin, and IL-1RA serve as reliable predictors for seroma formation after incisional hernia repair. Hernia. 2011; 15: 69-73 22. Okholm M, Axelsson CK. No effect of steroids on seroma formation after mastectomy. Dan Med Bul. February. 2011; 58(2): 1-5 23. Agrawal A, Abiodun A, Kwok Leung Cheung. Concepts of seroma formation and prevention in breast cancer surgery. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2006; (76): 1088-1095 24. Jamal Bullocks, Bob Basu, Patrick Hsu et al. Prevention of hematomas and seromas. Semin Plast. Surg. 2006; 20: 233–240 25. Johnson L, Cusick T, Helmer S, Osland J. Influence of fibrin glue on seroma formation after breast surgery. Am J Surg. 2005; 189(3): 319–323 26. Oertli D, Laffer U, Haberthuer F, Kreuter U, Harder F. Perioperative and postoperative tranexamic acid reduces the local wound complication rate after surgery for breast cancer. Br J Surg. 1994; (81): 6: 856-859 27. Marts BC, Naunheim KS et al. Conservative versus surgical management of chylothorax. AMJ surg. 1992; 164: 532-535 28. Kocdor MA, Kilic Yildiz D, Kocdor H, et al. Effects of locally applied 5-Fluorourarcil on the prevention of postmastectomy seromas in a rat model. Eur surg res. 2008; 40: 256-262 29. Abai B, Zickler RW, Pappas PJ, Lal BK, Padberg FT Lymphorrhea responds to negative pressure wound therapy. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2007; 45(3): 610-613 30. Greer SE, Adelman M, Kasabian A, Galiano RD, Scott R, Longaker MT. The use of subatmospheric pressure dressing therapy to close lymphocutaneous fistulas of the groin. British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 2000; 53(6): 484-487 31. Vedenskiy AN. Varicose disease. L.: Medicine, 1983. 208 p. Russian (Vedensky A.N. Varicose disease. L.: Medicine, 1983. 208 p.) 32. Azuma R, Takikawa M, Nakamura S, Sasaki K, Yanagibayashi S, Yamamoto N, et al. Indocyanine green fluorography in Plastic Surgery and Microvascular Surgery. The Open Surgical Oncology Journal. 2010; 2: 48-56 33. Lohrmann C., Foeldi E, Langer M. Lymphocutaneous fistulas: pre-therapeutic evaluation by magnetic resonance lymphangiography. British Journal of Radiology. 2011; 84 (1004): 714-718

View statistics

Loading metrics...

Links

- There are currently no links.