Differential diagnosis of articular syndrome

What are the differences between inflammatory synovitis and degenerative joint disease?

What are the clinical variants of the onset of arthritis in various diseases?

What laboratory tests are the most informative?

Articular syndrome is an almost universal manifestation of rheumatic diseases; its differential diagnosis underlies the determination of the nosological form, and therefore serves as a justification for the choice of therapeutic approach. In advanced stages of the disease, when there are organic changes in organs and tissues, the diagnostic problem is greatly simplified. Serious analysis is required at the onset, often represented exclusively by arthralgias.

Examination of patients complaining of arthralgia is aimed at identifying which structures of the musculoskeletal system are the source of pain or dysfunction. Joints are composed of surfaces of articular cartilage, bone, ligaments, and synovium. The joint space is not an unfilled space, as it seems to us when examining radiographs, but is represented by articular cartilage, transparent to X-rays; therefore, the degree of destruction of cartilage can be assessed radiographically by measuring the distance between two bone surfaces. Cartilage differs from bone in its more elastic composition, has a lower coefficient of friction and, most importantly, does not have the restorative abilities of bone. Therefore, cartilage damage must be considered as an irreversible process.

Cartilage defect or loss can occur in two ways:

- mechanical abrasion, as happens with osteoarthritis;

- erosion as a consequence of inflammatory synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis or other rheumatic diseases.

The synovium extends between the osteochondral borders on both sides and does not normally cover the articular cartilage. Its surface is represented by one or two layers of synoviocytes, capable of morphological adaptation, reflecting the function performed by the cell at the moment - synthetic or phagocytic. The histological picture of the initial stage of inflammatory synovitis is similar in most diseases. For example, it is impossible to distinguish ankylosing spondylitis from rheumatoid arthritis with a biopsy of the synovial membranes. Only in certain situations, for example in the case of tuberculous arthritis, can the diagnosis be based on biopsy findings.

As rheumatoid arthritis progresses, the process acquires the following characteristic features: erosive synovitis develops, corroding both cartilage and bone. Synovial villi, hypertrophied during the inflammatory process, are attached to the adjacent edge of the articular cartilage, creeping onto its surface. This inflammatory tissue replaces cartilage. This cartilage-replacing tissue is known as pannus and is composed of fibrous tissue infiltrated by chronic inflammatory cells, including mast cells. At the edge of the articular cartilage, the pannus replaces bone tissue, causing the occurrence of erosions detected by x-ray examination. Pannus can also penetrate the subchondral bone plate and grow in the subchondral bone.

Because cartilage is destroyed more quickly, progressive erosive synovitis appears on radiographs first as cartilage loss, then as periarticular bone erosion. It is important to note that persistent synovitis prevents the formation of osteophytes adjacent to the diminishing cartilage tissue. So, the radiological signs of chronic persistent synovitis are:

- loss of cartilage;

- Usuration of the bone adjacent to the places of thinning of the cartilaginous plates;

- no signs of osteophytes.

As the disease progresses, the vascularization of the synovium decreases (compared to earlier stages), which, on the one hand, is associated with fibrosis as a stage in the evolution of the disease, and on the other, with the immobility that develops as a result of fibrosis. The so-called “burnt-out rheumatoid arthritis” is formed. This expression can be considered unfortunate, since although physical examination reveals the absence of hyperthermia, effusion and hyperemia, the patients still have morning stiffness, an increase in ESR and, more importantly, with dynamic radiographic observation, bone usuration increases.

Degenerative joint diseases have completely different characteristics.

- No synovitis. (This, by the way, explains the low effectiveness of anti-inflammatory drugs for this disease.)

- The cartilage defect is localized in areas of mechanical damage. Often there is a juxtaposition of almost normal cartilage with areas where the cartilage is completely worn out.

- The appearance of osteophytes in the vicinity of areas of cartilage defects.

Only in the later stages of osteoarthritis can pain occur both during exercise and at rest and disturb night sleep. Since cartilage does not have a regenerative ability, once a symptom complex has arisen, it tends to progress. However, in cases of ordinary household loads, the cartilage wears out very gradually and the deterioration increases gradually, over the years. Symptoms of synovitis persist at rest and are only accentuated during exercise.

Morning stiffness, characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and other systemic diseases, usually lasts for at least two hours. This symptom is associated with a physiological drop in the level of corticosteroids in the blood in the pre-dawn hours and with the accumulation of cytokines from the inflammatory fluid during sleep. Morning stiffness with osteoarthritis is transient, lasts no more than 20 minutes and does not coincide with objective symptoms. The duration of morning stiffness in systemic rheumatic diseases is directly dependent on the severity of inflammatory reactions. For example, one of the important criteria for remission of rheumatoid arthritis is the complete disappearance of morning stiffness.

With the exception of gout, synovitis is a manifestation of systemic diseases; patients show signs of a generalized process. Osteoporosis, on the contrary, is formed due to local mechanical effects and, naturally, is not accompanied by systemic effects.

Osteoarthritis affects almost exclusively the joints that experience weight bearing - the hip, knee, and first metatarsophalangeal. Polyarthrosis, as a rule, is familial in nature and is caused by genetic inferiority of cartilage and ligamentous apparatus. The appearance of deformations in the elbows, metacarpophalangeal, and wrist joints should be considered as a manifestation of inflammatory reactions.

As soon as degenerative joint damage begins to manifest itself clinically, its typical signs can also be detected on radiographs. At the same time, the initial stages of synovitis are X-ray negative. Usuration of bones is visible only when the process is advanced. Differential diagnostic characteristics of articular syndrome in osteoarthritis and systemic synovitis are presented in the table.

For many systemic diseases, the diagnosis becomes obvious only after a few months, when the classic symptom complex is formed. Significant diagnostic difficulties always arise in the early stages. However, there are certain characteristic opening options:

- acute monoarthritis,

- migratory arthritis,

- intermittent arthritis,

- spreading arthritis.

Acute monoarthritis most often occurs with septic lesions and synovitis, with microcrystalline arthritis. Both diagnoses can be verified quite easily using a diagnostic puncture and cultural or crystallographic analysis of synovial fluid.

The term “migratory” arthritis is used in cases where the inflammation in the initially affected joint completely subsides and the process resumes in the next ones. This option is quite rare and is characteristic of rheumatism and gonococcal arthritis.

Intermittent outbreaks of arthritis after a long period of remission occur in gout, spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and arthritis associated with intestinal infection.

Spreading arthritis is the most nonspecific: in this case, with persistent inflammation in the initially affected joint, more and more joints are involved in the process.

When making a diagnosis, it is very important to take into account family history, for example, information about the presence of Heberden's nodes, gout, spondylitis, SLE, and hemochromatosis in the family.

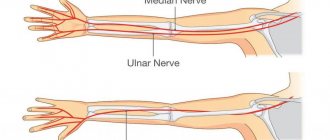

When physically examining joints, three parameters must be taken into account: pain (sensitivity), swelling, and mobility. Synovitis is characterized by pain (sensitivity) throughout the entire joint. If the pain is localized only in a certain area (point) of the joint, you should think about a local, local cause of its occurrence, such as bursitis, tenosynovitis or fracture. Bone crepitus and osteophyte formation are cardinal features of degenerative joint disease. While effusion and thickening of the synovium are typical for synovitis. It is important to remember that soft tissue swelling is not detected on physical examination of axial joints and is rarely detected in proximal joints such as the shoulder or hip. In addition to the range of motion protocol, it can be noted whether there is a significant difference between passive and active range of motion. This difference indicates that the lesion is due to muscle weakness, tendon rupture, or neurological pathology, but not to bone blockage.

Analysis of the involvement of a specific joint in the process can be very important, since some joints are never affected in certain diseases and, on the contrary, for many nosologies there are typical localizations.

The temporomandibular joint, for example, is often involved in rheumatoid arthritis but is never involved in gout. The cervical spine is often affected in RA, spondylitis and osteoarthritis, but never in gonococcal arthritis or gout. The laryngeal joints are affected in a third of all cases of rheumatoid arthritis and are extremely rare in other types of inflammatory joint lesions. Characteristic symptoms of inflammation of the joints of the larynx are pain in the throat, localized in the larynx and accompanied by a change in voice. Both symptoms may only be evident for a few hours in the morning. Synovitis usually develops in non-weight-bearing joints of the upper extremities, whereas osteoporosis does not occur in the elbow, metacarpal, or wrist joints. Spondylitis, as a rule, progresses from the sacroilial joint up the spine, the location of which may vary. Rheumatoid arthritis, in turn, affects only the cervical region and does not cause lower back pain.

It has been observed that some joints are never affected at the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. These are the so-called articular exceptions - distal interphalangeal joint, metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb, proximal interphalangeal joint of the fifth finger.

Study of the olecranon region is often very fruitful in the evaluation of rheumatic diseases, since rheumatoid nodules, gouty tophi or psoriatic plaques are most often localized here. Rheumatoid nodules are also often located in the iliac region, on the ears, along the spine and may be indistinguishable from tophy on physical examination. However, rheumatoid nodules can be detected already in the early stages of the disease, are very characteristic of the initial outbreak and tend to decrease in size over time. Tophi often occur earlier than several years after the patient is given a clinically obvious diagnosis. Sometimes specific diagnosis requires biopsy of the nodule or aspiration of the tophi to identify crystals. Gout is clearly diagnosed by detecting uric acid crystals in synovial fluid aspirated from the inflamed joint. Serum uric acid levels can only indicate susceptibility to gout.

When conducting an X-ray examination, it should be remembered that: 1) osteoporosis is nonspecific and is often a consequence of immobility associated with pain; 2) narrowing of the joint space indicates loss of cartilage; 3) new bone growths indicate osteosclerosis, are a sign of osteophytes and the absence of synovitis; 4) soft tissue swelling is best diagnosed by physical examination.

It is important to remember that x-rays show the condition of the bones, not the cartilage or synovium, and since the destruction of cartilage takes time, the x-ray usually lags the clinical picture by several weeks. More specific information appears after three to four years, when erosion (usuration) of the articular cartilage occurs with granulation connective tissue - pannus.

The most informative laboratory test for rheumatoid arthritis is the latex test, aimed at identifying rheumatoid factor.

What is the diagnostic value of the latex test?

About 5% of healthy young people and 15% of older people have a positive latex test. Since rheumatoid arthritis affects approximately 1% of the population, it can be stated that only 15-20% of seropositive people suffer from rheumatoid arthritis. Only 85% of patients with an established diagnosis are seropositive. Thus, it is obvious that the latex test does not confirm or exclude the presence of the disease. The latex test is also often positive in other systemic connective tissue diseases, as well as in some chronic inflammations such as tuberculosis, gout, and bacterial endocarditis.

Once a positive titer of rheumatoid factor is detected, it persists throughout the disease. Therefore, there is no particular need for repeat studies in patients with obvious rheumatoid arthritis. However, serological tests are usually negative in the initial stages and become positive as the disease progresses.

This reaction has prognostic significance. In general, in seropositive patients the process is unfavorable; subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules are often involved. It should be noted that the detection of rheumatoid factor increases with age. In general, the classic debut of the disease, manifested by a typical symptom complex and a high titer of rheumatoid factor, is characteristic of patients aged 55-65 years. In this group of patients, the process progresses rapidly, and erosion of the articular surfaces develops early.

Negative results of a study of rheumatoid factor during long-term observation of a seriously ill patient force us to look for another disease that occurs with rheumatoid-like joint syndrome.

| Difference between degenerative joint disease and inflammatory synovitis | ||

| Subjective symptoms | 1. Symptoms only during exercise | 1. Symptoms are present even at rest |

| 2. Anti-inflammatory drugs are ineffective | 2. Anti-inflammatory therapy helps | |

| 3.Gradually progressive deterioration | 3. Current in the form of attacks | |

| 4. No signs of acute inflammation | 4. Exacerbations in the form of outbreaks | |

| 5. No systemic manifestations | 5. Systematic | |

| 6. No morning stiffness | 6. Morning stiffness | |

| Objective symptoms | 1. Predominant damage to joints under weight load | 1. Elbows, hands, metacarpophalangeal joints |

| 2. Crunching and hypertrophy of bones | 2. Soft tissue swelling | |

| 3. Radiological signs of local cartilage defect hyperostosis | 3. Radiological signs may be absent. Characterized by diffuse cartilage loss and absence of new bone growths | |

| Treatment | Surgical | Medication |

Traumatic arthritis

Septic and especially traumatic arthritis are most similar to gout in terms of the severity of inflammatory manifestations, although their incidence is significantly lower compared to gout. In the case of traumatic arthritis, identifying the provoking factor can only partially help in making the correct diagnosis, since with gout there is often a chronological connection with injury, which explains why patients primarily turn to a traumatologist or surgeon. X-ray examination of the distal parts of the feet may not be informative, since at the first attack of gouty arthritis there is still no characteristic X-ray symptom of a “punch” (to be discussed further). The level of uric acid at the time of an attack may also not exceed the laboratory norm, which is explained by the redistribution of urates in the blood with their precipitation into crystals. In this case, practically the only method for verifying the diagnosis is puncture of the affected joint. In classical cases, the presence of hemarthrosis will indicate traumatic arthritis. In the absence of blood, the level of inflammatory response must be assessed, which may be difficult due to the small amount of synovial fluid obtained from the joint. However, to detect EOR crystals, it is enough to obtain a minimal amount of liquid (no more than a drop). An additional fact in favor of gouty arthritis may be the fairly rapid relief of the last NSAID, especially at the onset of the disease.

Pyrophosphate arthropathy

Pyrophosphate arthropathy (PAP) is a type of microcrystalline arthropathy. It develops predominantly in older people (usually no younger than 55 years), approximately equally often in men and women. Clinical and radiological differences between gout and PAP are summarized in Table. 2. Cases of detection of both types of crystals in one patient are described. In 90% of cases, PAP affects the knee, shoulder joints and small joints of the hands. It is noteworthy that the onset of gout with arthritis of the knee joints is not casuistry, especially in the presence of a history of trauma, and vice versa, pseudogout with involvement of the PFJ occurs. Involvement of the small joints of the hands in gout is observed more often at a late stage of the disease, and the shoulder joints can be considered “exception” joints even at a late stage.

To verify the diagnosis at an early stage, the key point is polarization microscopy of the synovial fluid, which makes it possible to identify calcium pyrophosphate crystals. In later stages of PAP, a characteristic radiological picture appears: chondrocalcinosis, usually of the menisci, but also of the articular cartilage.

Ankylosing spondylitis

Quite often it is necessary to distinguish between gout and ankylosing spondylitis (AS). This is due to the fact that these diseases are characterized by the similarity of a number of signs, namely: male gender, frequent involvement of the joints of the lower extremities, monoarthritis, sudden onset of arthritis. However, the clinical picture of AS has its own characteristics. These are pain in the spine with stiffness and limited excursion of the chest, night pain in the lower back with radiation to the buttocks, long duration of arthritis (from several weeks to months). X-ray examination shows the presence of sacroiliitis. The determination of HLA-B27, detected in almost 90% of patients, helps in diagnosing AS.

* Criteria A and B (detection of crystals) are independent.

↑

Psoriatic arthropathy

The differential diagnosis of gout with psoriatic arthropathy causes serious difficulties. The latter is characterized by damage to the distal interphalangeal joints, although any joints can become inflamed. X-ray changes in the joints may be similar (with the exception of the classic “pencil in a glass” and “punch” picture). The main symptom that prompts a diagnostic search is GU, which often accompanies psoriatic arthritis and is an indirect sign of the activity of skin manifestations. It should be remembered that even in the presence of cutaneous psoriasis, the final diagnosis of joint damage is established after examining the synovial fluid for crystals. In our practice, we encountered a combination of skin psoriasis and gout, confirmed by the detection of crystals.

Clinical picture of gouty arthritis

Classic gouty arthritis: acute, sudden onset, usually at night or in the morning, pain in the area of the metatarsophalangeal joint of the first finger.

An acute attack with rapid development of severe joint pain and swelling that peaks within 6–12 hours is highly diagnostic for gout, especially when accompanied by skin erythema (Figure 1).

Arthritis of this localization can also occur in other diseases, however, the presence of such typical signs as severe hyperemia and swelling in combination with severe pain in the PFJ of the first finger makes clinicians think specifically about gouty arthritis.

Typical provoking factors are: alcohol intake, heavy consumption of meat and fatty foods, visiting a bathhouse (hypovolemia), surgery, microtrauma associated with prolonged stress on the foot or a forced position (while driving, on an airplane, etc.).

Common mistakes

The combination of arthritis with high levels of uric acid in the blood makes diagnosis easier. But, as our observations show, the diagnosis of gout is made only in the 7th–8th year of the disease. This is primarily due to the peculiarity of the course of gouty arthritis, especially at the onset of the disease: fairly rapid relief of arthritis even without treatment, rapid pain relief with the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or analgesics. The characterological characteristics of patients are important: an extremely low level of compliance, which is partly due to the sexual dimorphism of the disease: gout affects mainly men of socially active age (45–50 years).

MUN crystals.

An independent and sufficient sign for the diagnosis of gout is the detection of MUN crystals in the most accessible media for research - synovial fluid. The formation of MUN crystals and the inflammation that occurs in response constitute the pathogenetic essence of the disease. The study of the phenomenon of formation of EOR crystals showed their uniqueness and obligatory nature for gout. Their detection is the absolute certainty of the diagnosis (Fig. 2a).

Tophi.

EOR crystals, resulting from GI, are deposited in the form of deposits called tophi. As a rule, microdeposits are found in many organs and tissues, and in the case of chronic gout, macrotophus are also formed.

Tophi is described by morphologists as a kind of granuloma, consisting of crystalline masses surrounded by an infiltrate of inflammatory cells (Fig. 2b). Proteins, lipids, calcium, and polysaccharides are also components of tophi. Subcutaneous tophi are the most famous because they are easily detected. More often they are localized in the area of the toes and hands, knee joints, elbows and ears. The same deposits are formed in the kidneys, heart, joints, and structures of the spine. Finally, we recently discovered the phenomenon of deposition of EOR crystals in the gastric mucosa.

Synovial fluid is the most accessible for research, and crystals can be found even in non-inflamed joints. Polarizing microscopy is used to identify crystals. EOR crystals are birefringent, needle-shaped, blue or yellow in color depending on their location relative to the beam; their size can vary from 3 to 20 mm. Overall, despite interlaboratory variations, the sensitivity and specificity of this method are considered to be high.

Acute calcific periarthritis

Episodes of pain and inflammation in the joints, including in the area of the PFJ of the first finger, can occur with acute calcific periarthritis. Large joints are most often affected: hip, knee, shoulder. Deposits of amorphous hydroxyapatites, which form in the acute stage in the ligaments or joint capsule, may subsequently disappear and then reappear, causing repeated attacks of arthritis. Calcific periarthritis is more common in women or in patients with uremia on hemodialysis.

Septic arthritis

Septic arthritis is clinically similar to gouty arthritis and is also characterized by the development of hyperemia, hyperthermia, pain, swelling and joint dysfunction. Septic arthritis is accompanied by fever, increased ESR, and leukocytosis, which is not typical for gout or is observed in late chronic polyarticular course. Septic arthritis can be caused by intra-articular injections of drugs for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and osteoarthritis (OA), as well as immunosuppression.

Gout and septic arthritis can develop in the same patient, so if bacteria are detected in the synovial fluid, it should also be examined for the presence of MUN crystals.