A rupture of the acromioclavicular joint occurs at the junction of the humeral process of the scapula and the clavicle. This region is usually called the arcomion. The frequency of damage to this area of the clavicle reaches 15-17% among the total number of ruptures and dislocations.

The injury ranks third in popularity, after injuries to the shoulder and forearm. The risk group includes active young people and professional athletes.

Anatomical features

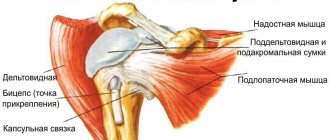

The collarbone, humerus and scapula make up the shoulder girdle. The acromioclavicular joint is a low-moving joint that connects the collarbone and scapula.

The joint is supported by bone formations that secure the joint with strong ligamentous tissue. The articular ends are surrounded by a closed capsule, which is filled with synovial fluid.

Causes of damage to the acromion joint

Among the main reasons that lead to rupture of the acromioclavicular joint, doctors note:

- injury during sports competitions (a similar rupture is often found among goalkeepers of football and hockey teams, who forcefully fall their shoulder to protect the goal);

- ruptures when practicing contact sports (judo, boxing, taekwondo or sumo);

- damage from a fall on an outstretched arm (often resulting from slipping on ice in the winter);

- damage resulting from leading an active lifestyle (after careless roller skating, skiing or skating).

Arthroscopic stabilization for habitual shoulder dislocation

Arthroscopy for recurrent shoulder dislocation is considered as a treatment for frequent episodes of instability that prevent a person from performing normal arm movements or playing sports. When all other therapies have been tried, arthroscopic stabilization is the next step. The results of surgery are most effective when the patient undergoes postoperative rehabilitation, including physical therapy and special exercises to develop the joint. Read more about arthroscopy for habitual joint dislocation...

Types of ruptures of the acromioclavicular joint

Doctors distinguish between complete and incomplete ruptures of the acromioclavicular joint. Damage to the articulation can lead to displacement of the clavicle; ruptures occur with displacement of the clavicular bone upward or forward.

According to the degree of deformation, the gap is divided into:

- lightweight, which does not entail displacement of the collarbone. The damage has a minimum tear size of 2-3 mm;

- medium, leading to a tear of the ligament and a change in the location of the collarbone. An expansion of the joint space of up to 5 mm is detected;

- severe, causing serious damage to joints. The size of the tear exceeds 7 mm.

Depending on the moment of injury, ruptures are divided into:

- fresh. The damage was received no later than 3 days before the request for help;

- stale. The injury occurred in the period from 3 days to 3 weeks before the visit to the doctor;

- outdated. The rupture occurred later than 3 weeks before seeking treatment.

Department of Traumatology and Orthopedics

article in PDF format

QUOTE LINK:

1E. B. KALINSKY, 1A. D. CHENSKY, 2B. M. KALINSKY, 1L. A. YAKIMOV, 1I. N. ROZOCHKIN

1GBOU VPO First Moscow State Medical University named after. THEM. Sechenov, Moscow

2City Clinical Hospital named after S.P. Botkin of the Moscow City Health Department, Moscow

Information about the authors:

Kalinsky E.B. – Ph.D. First Moscow State Medical University named after I.M. Sechenov. Department of Traumatology, Orthopedics and Disaster Surgery. Department Assistant; e-mail: [email protected]

Chensky A.D. – Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor. First Moscow State Medical University named after I.M. Sechenov. Department of Traumatology, Orthopedics and Disaster Surgery. Professor of the department

Kalinsiky B.M. – GBUZ DZM GKB im. S.P. Botkin. Head Trauma department

Yakimov L.A. – Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor. First Moscow State Medical University named after I.M. Sechenov. Department of Traumatology, Orthopedics and Disaster Surgery. Professor of the department

Rozochkin I.N. – First Moscow State Medical University named after I.M. Sechenov. Faculty of Medicine, 5th year, 47th group

The study of patients with injuries to the shoulder and acromioclavicular joints (ACJ) dates back to ancient times. From the time of Hippocrates to the present day, research into this pathology and the development of methods for its treatment has continued. The incidence of this injury in the modern world reaches 26.1%, ranking third after shoulder and forearm dislocations. This review article presents to your attention the main historical stages in the study of the problems of traumatic injury to the ACJ, the evolution of approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of patients, as well as the prospects for the development of this scientific and practical area of orthopedics and traumatology.

Key words: acromioclavicular joint, AC joint, AC joint reconstruction, surgical treatment, shoulder joint.

Introduction

Damage to the acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) has been an important and pressing problem for many centuries. From the time of Hippocrates to the present day, the study of this pathology and the development of methods for its treatment have continued. The incidence of this injury in the general structure of injuries to the musculoskeletal system reaches 26.1%, occupying third place after dislocations of the shoulder and forearm [3]. At all times, studying the characteristics of treatment and its long-term results, a large number of complications, unsatisfactory outcomes and poor functional results can be traced. A significant decrease in quality of life due to chronic pain syndrome, limited arm movements and decreased muscle strength leads to the need to develop new treatment methods.

In this article, you will be presented with the main historical stages in the study of the problems of traumatic injury to the ACJ, the evolution of approaches to treating patients and the prospects for the development of this scientific and practical area of orthopedics and traumatology.

Epidemiology

The study of the features of the mechanism of shoulder girdle injury and its consequences, as well as the analysis of statistical material on this topic, became popular in the first half of the last century. The most common cause of ACJ injury is direct impact on the shoulder joint. However, the predominant mechanisms of injury differed across time periods. Thus, according to WHO statistics in 1940, about 89% of ACL injuries were caused by various sports, in particular football, horse riding or ring training [3]. The second most popular injury, according to the work of M. iel in 1937, was occupied by injury caused by a direct fall of a load onto the ACS area, for example, among miners during rockfalls. [52]

In the modern world, the incidence of traumatic dislocation of the acromial end of the clavicle ranges from 12.5 to 26.1% in the structure of skeletal injuries and 11% in the structure of sports injuries. AC joint ruptures rank third in frequency after dislocations in the shoulder and elbow joints. Most often, the injury occurs between the ages of 15 and 25 years. It is more common among athletes involved in contact sports. The male/female ratio is approximately 5-10:1.

The role of the acromioclavicular joint in the biomechanics of the upper shoulder girdle

The shoulder joint is a ball-and-socket joint with a large range of motion. However, these movements are significantly limited by the capsular-ligamentous structures of the joint, which, at the same time, have a stabilizing function. Major anatomical studies conducted in the middle of the last century showed the important role of the acromioclavicular joint in the movements of the arm and the functioning of the shoulder joint as a whole.

The first scientific reports on stereotypes of movements in the ACJ were published in 1944 by Y. Inmann and co-authors, who were able to show on the basis of anatomical experiments that movement of the clavicle around its own longitudinal axis is possible. It makes a significant contribution to the functional component of the biomechanics of shoulder movements. The amplitude of rotation, in some cases, was up to 45 degrees. It has been shown that similar movements in the clavicle occur when the arm is abducted 160–180 degrees. What is noteworthy is that it was at this moment (excessive abduction of the arm) that the spring and stabilizing support due to the rotation of the clavicle was of greatest importance for the joint. [2] Later, in 1959, the German researcher G.waschmuth clearly demonstrated that combined movements of the scapula in the sagittal and frontal planes make it possible to increase the amplitude of internal rotation of the shoulder up to 40 degrees, and rotation of the scapula around the longitudinal axis of the body makes a significant contribution (up to 50 degrees) in abduction of the arm. However, during the same historical period, the Americans Kennedy and Cameron (1954, 1959) entered the discussion, publishing a study proving that with arthrodesis of the AC joint, movements in the shoulder joint can be fully preserved. Without emphasizing the role of the clavicle and scapula in the biomechanics of shoulder joint movements, they reported that synchronous movements of the scapula and clavicle during AC arthrodesis are almost as effective as when maintaining normal motion in them [2, 7]. In 1965, D. Dempster and co-authors dispelled this theory, explaining it by the good compensatory properties of the shoulder joint capsule. In a large anatomical experiment, these German scientists showed the enormous importance of the ACJ, as well as its main stabilizing structures—the coracoid and clavicular-acromial ligaments. [2, 16] Based on studies by M. Sommer and P. Marschner in 1959, which showed the strength of these ligaments and the peculiarities of their structure, D. Dempster and co-authors put forward a theory about their key role in maintaining the stability of the ACJ, and therefore in the successful functioning of the shoulder joint They showed their variable and consistent tension during all types of movements of the shoulder joint, and suggested a partial loss of the most important medial support and stability of the shoulder joint when they fail.

In 1966, JD Tosy and RH Sigmond concluded that direct or indirect traumatic force on the clavicle leads to AC joint rupture. They drew attention to the fact that in this case, radiological and clinical signs of complete or partial dislocation of the acromial end of the clavicle arise. [51.1] Almost in parallel with them, domestic scientist K.A. Petrakov suggests the development of partial damage to the trapezius and deltoid muscles as a result of such an injury and the possible significance of this in the biomechanics of movements and functions of the ACJ. [20] A few years later, w. Rosenor and R. Pedersen (1974) conducted and published experimental data in which they performed alternate and simultaneous destruction of the acromial clavicular and coracoid ligaments, as well as the capsule and meniscus of the joint, partially the deltoid and trapezius muscles. In their work, they were able to explain under what conditions subluxation occurs and under what conditions dislocation of the acromial end of the clavicle occurs. They showed that when the joint capsule and acromioclavicular ligament were damaged, a partial violation of congruency in the ACJ occurred, and when all the main structures were destroyed, a dislocation occurred.

In the literature of the mid and second half of the 20th century, the authors unanimously agreed on the important role of the AC joint in the biomechanics of movements of the upper limb and on the functional significance of the main capsular-ligamentous structures of the acromial end of the clavicle, which play a key role in maintaining the stability of the AC joint.

Historical stages in the development of diagnostics

How did the evolution of methods for diagnosing AC joint damage occur? The main impetus for progress in the study of traumatic injury to the AC joint was the discovery and gradual introduction of radiography into practice. It is known that in 1918 the first X-ray clinic was created in Russia, and by the middle of the 20th century, the vast majority of medical institutions in the USSR, Western Europe and North America were equipped with X-ray equipment. Initially, the structures of the upper limb girdle were assessed on a plain chest x-ray. But already in 1938, R. Shoen proposed the use of targeted radiography of the ACJ, as well as the study of this area in the lateral projection with the healthy arm raised up. He suggested that the sign of cross-overlapping shadows from the clavicle and the acromion process of the scapula may indicate the presence of a dislocated clavicle. Later, in 1940, Uzedel proposed supplementing X-ray diagnostics with the author’s axial image of the shoulder joint, in which he described the most likely signs of AC joint rupture. [6,49] However, all the proposed methods only made it possible to identify damage to the AC joint, without making it possible to assess its degree. In 1957, L. Bohler and co-authors proposed a new research technique: functional radiography of the shoulder joint. [31] According to the method of L. Bohler, which later became the gold standard and remains relevant to this day, the study was carried out covering both shoulder joints, in the anteroposterior projection, at a focal length of 2 meters and with loads on both shoulder joints weighing 5– 10 kg. This technique made it possible to begin to very accurately differentiate patients with complete and partial damage to the AC joint. [6]

Modern diagnosis of dislocations of the acromial end of the clavicle has moved much further with the development of computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [36], ultrasound methods, etc. However, at present, the technique proposed by L. Bohler in 1957 functional radiography is an integral part of diagnosis, playing a critical role in deciding on the patient’s treatment tactics [42].

Evolution of classification

For many years, there was no separate classification of AC joint injuries. According to past literature, all lesions of this joint were considered within the framework of the classification of shoulder injuries. In the middle of the 20th century, against the background of great attention paid to the issues of surgical anatomy and biomechanics of joints (examples of which are described above), new classifications of AC joint injuries were created without taking into account the shoulder joint. Of particular significance is the 1963 JD Tosy classification. [26,50] Based on only 3 categories, it has found its application in practice, thanks to the special attention paid to the ligamentous apparatus of the acromial clavicle. It is briefly described as follows: Type I: Minimal sprain of the acromial clavicular ligament and joint capsule. The acromial clavicular joint remains stable, there is no upward protrusion of the lateral end of the clavicle; Type II: The acromiocleidoclavicular ligament and joint capsule are damaged (partial tear). The coracoid ligament remains intact. The acromioclavicular joint becomes unstable. X-ray shows that the lateral end of the clavicle extends upward above the acromial process by no more than the thickness of the acromial process itself (subluxation);

Type III: Complete rupture of the acromial clavicular and coracoid ligaments with dislocation of the lateral end of the clavicle.

A little later, around 1967, this classification was refined and improved by B. Alman. [27,29] Here's what it looked like: 1st degree: overstretching of the AC joint without deformation and radiological changes; 2nd degree: rupture of the capsule and ligamentous apparatus of the ACJ, without damage to the clavicular-coracoid ligament, accompanied by moderate deformation and an x-ray picture of upward displacement of the acromial end of the clavicle; Stage 3: complete dislocation in the AC joint with rupture of all ligaments in this area.

In modern practice, the CARockwood classification, proposed in 1998, refined and supplemented in 2008 by A.A., is actively used. Sorokin. [19] This classification takes into account the presence of damage to each of the two main ligaments (acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular) that provide stability to the AC joint, the nature of the displacement of the acromial end of the clavicle, the duration and consequences of the injury, as well as the presence of degenerative changes in the AC joint area and the shoulder joint. Here is its summary: I degree – damage is not accompanied by displacement of the clavicle;

II degree – subluxation of the clavicle (rupture of the acromioclavicular ligaments without damage to the coracoclavicular), A – before two weeks (damage to the ligaments without degenerative changes in the structures of the shoulder girdle), B – after two weeks (with degenerative-dystrophic changes in the structures of the shoulder girdle);

III degree - dislocation of the clavicle (rupture of the acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments), A - before two weeks (damage to the ligaments without degenerative changes in the structures of the shoulder girdle), B - after two weeks (with degenerative-dystrophic changes in the structures of the shoulder girdle);

IV degree - dislocation of the clavicle with posterior displacement (rupture of the acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments with separation of the fibers of the trapezius muscle from the acromial end of the clavicle), A - before two weeks (damage to the ligaments without degenerative changes in the structures of the shoulder girdle), B - after two weeks (with degenerative-dystrophic changes in the structures of the shoulder girdle);

V degree - dislocation of the clavicle with a significant upward displacement (rupture of the acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments with separation of the tendon fibers of the trapezius and deltoid muscles from the distal part of the clavicle), A - up to two weeks (damage to the ligaments without degenerative changes in the structures of the shoulder girdle), B - after two weeks (with degenerative-dystrophic changes in the structures of the shoulder girdle). The CARockwood classification is currently universal, actively used in everyday surgical practice and in international scientific research in this area. [28, 34, 38, 48]

Treatment

The study of patients with injuries of the shoulder and acromioclavicular joints (ACJ) dates back to ancient times. The deciphered medical teachings of the ancient Egyptians testified to their mastery of the technique of applying “fixed bandages” for injuries to the bones and joints of the upper limb. Conservative treatment of patients with injuries to the joints of the shoulder girdle using “dry bandages” is also indicated in the works “On Fractures” and “On the Reduction of Joints” by the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates (IV century BC) and the ancient Roman physician Celsus (I century AD). ). Moreover, it is known that in his immortal works, the great Hippocrates for the first time separated the concepts of “dislocation of the shoulder” and “dislocation of the acromial end of the clavicle,” which before him were considered the same injury. As scientists gained experience and knowledge, they improved conservative methods of treating patients with AC joint injury. We are talking about the works of prominent Russian scientists, for example, xx Salomon (1769-1851) “Some notes on dislocations”, E. O. Mukhina (1766-1850) “The first principles of bone-setting science”, N.I. Pirogov (1810-1881) anatomical “frozen sections”, as well as foreign authors - K. Reiter (1846-1890), Littl (1810-1894) and others. The emergence and active development of shoulder joint surgery at the beginning of the last century once again drew attention to the study of the consequences of injury to the acromioclavicular joint, pushing orthopedic traumatologists of those times to develop methods of surgical treatment for such patients. In 1939 I.M. Chizhin proposed a treatment method that involved applying a frame to fix the collarbone. This method of conservative treatment is well known to Russian traumatologists. The structure was made of four slats, which were tied together using a plaster bandage, lined with cotton wool and reinforced with ordinary soft bandages. The height of the frame should be equal to the distance from the top of the shoulder joint to the iliac crest. The Chizhin frame was installed in the armpit on the side of the damaged clavicle, the shoulder girdle was raised on the affected side until the lower crossbar of the frame was installed on the iliac crest, and then attached to the body with plaster bandages. [21] Some authors of that time proposed their own modifications of similar designs, for example V.V. Gorinevskaya (1938), V.V. Pirozhenko (1955), etc. [5,17] In the literature of those years, there was an active discussion about the advisability of using these structures, in connection with the development of severe necrosis in the area of the elbow and shoulder joints, as well as frequent neurological disorders in the immobilized limb.

From 1955 to 1970, there was active development of methods for the conservative treatment of AC joint injuries. So, in 1955, the H. Howard bandage was proposed. It was based on a complex plaster-gauze orthosis, which provides more gentle fixation of the arm and the acromial end of the clavicle [39]. In 1961, M. Brosgol invented and successfully introduced into practice a fixator, which was fundamentally different from the H. Howard orthosis in the presence of a durable thoracolumbar corset. Thus, it was possible to increase the degree of rigidity of fixation, and also to avoid the use of bulky plaster splints [33]. Subsequently, some authors proposed their own modifications of the corset fixation, which essentially differed little from each other (M. Spigelman bandage, Hunkin corset). It is necessary to separately note the merits of B.K. Babich (thoraco-brochial plaster cast) and V.P. Salnikov (classical “trupe bandage” Fig. 1), who created original corset headbands that have been widely used since the 1970s. [18] Unfortunately, the new models of fixators also had serious drawbacks: when stopping swelling of the soft tissues in the area of injury during treatment and weakening the fixing properties of the bandage, it was often necessary to make repeated corrections.

In 1964, based on an analysis of the shortcomings and defects of the methods described above, E.S. Kozhukeyev introduced into practice the famous CITO tire with adjustment by a screw pilot. This made it possible to regulate the degree of fixation of the acromial end of the clavicle, carrying out slight correction of the treatment in the splint depending on dynamically changing circumstances (fluctuations in post-traumatic edema, the development of inflammatory changes in the skin and pressure sores of soft tissues in places of contact with the fixator, etc.). [12]

Scientists and doctors have been actively involved in the development and implementation of methods of conservative treatment at all historical stages of the development of medicine and continue to do so to this day. For example, kinesiotherapy and taping are a new and very promising direction in the functional treatment of patients with consequences of AC joint injuries. The essence of this method is to use adhesive tape (tape), consisting of three layers: textile, polymer-elastic and adhesive base. Tapes can stretch by 30-40% of their original length. Tapes of varying stiffness and elasticity are applied in the area of the shoulder joint and AC joint. This allows you to limit mobility and elastically fix the acromial end of the clavicle without resorting to the use of bulky structures.

With the beginning of the surgical era in world medical science, along with numerous conservative techniques, more aggressive surgical approaches began to appear. The first operation mentioned in the world literature was called “Suturing the clavicle and acromial end of the scapula with silver wire.” It was performed in 1861 by the American E. Coope.[40,41]

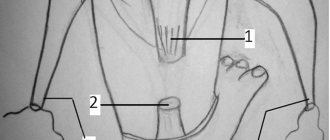

At the beginning of the 20th century, doctors had very scanty data on the biomechanics and function of the AC joint, as well as a small number of clinical and experimental studies of the pathology of this localization. However, already in 1928, W. Carrel performed plasty of the acromioclavicular ligament using a section of the patient’s fascia lata [35 ]. In 1940, G. Murray proposed his own treatment method, which involved closed transarticular fixation of the AC joint with pins passed through the skin (the pins remained outside). They were removed after 34 months. This technique has generated considerable debate due to its minimal invasiveness, but has not received widespread acceptance due to the risk of soft tissue infection along the wires. [45] Taking this into account, British specialists, V. Bosworth and co-authors, reported the first operation of “coracoclavicular screw fixation” (Fig. 2). The essence of the method was fixation with a screw inserted through the collarbone into the coracoid process of the scapula. Despite the apparent rigidity of the fixation, relapses were observed in a large percentage of cases, requiring additional postoperative immobilization with a plaster cast. [32]

In 1942, an orthopedist from the USA D. Phemister improved the G. Murrey method and proposed transarticular fixation with two wires, the ends of which should be immersed under the skin, but at the same time protrude above the surface of the acromial process of the scapula, to facilitate their removal after 2 months. [46] However, this technique has also not found widespread use.

Based on the methods described above, the development of radiological research methods and great scientific interest in the problems of AC joint rupture, reconstructive and fixation operations began to appear. So, in 1953 V.V. Gorinevskaya proposed her own method of plasty of the acromioclavicular ligament. In order to reduce the volume of the operation, she recommended using the supracromial fascia as donor tissue for the reconstruction of the ligamentous apparatus, thereby improving the well-known and widespread operation w. Carrel. [5,35] In the 1960s, special attention was given to the developments of I.A. Movshovich (lavsan-plasty of the coracoid ligament) and A.V. Kaplan (author’s method of combined fixation of the AC joint with pins and reconstruction of the ligamentous apparatus using transarticular fixation with pins ), which are still often used today. The essence that unites these operations is that, with the help of a guide, a Mylar tape is passed under the coracoid process of the scapula, the outer end of which is passed from behind and from top to bottom through the canal in the clavicle. The dislocation is adjusted and the knot on the tape is tightened. [11, 14].

In 1961, the LiGoldman fixation operation appeared, in which a special hook-shaped implant was located subacromially, and its curved end was fixed with a special screw to the acromion. This was the first prototype of the modern interlocking hook plate. [13, 30]

However, at that time, the bulkiness of the developed implant and the traumatic nature of the operation forced doctors to continue inventing and improving AC joint fixation operations. Thus, in 1976, a doctor from the USA improved the ancient method of G. Murry, performing additional tying of the needles with a wire loop, [44] and in 1986, E. Larsen changed this operation, proposing the transarticular insertion of two intersecting wires. [43]

The use of the described methods and their modifications led to a large number of unsatisfactory results, in the form of the development of contractures, migration of metal fixators, and frequent purulent-septic complications. They were replaced by submersible techniques for fixing the ACL. In 2002, the GE Fade and JE Scullion operation was published using a plate that has a hook-shaped end, which is placed under the acromion, and a part that is fixed to the collarbone with screws with a diameter of 3.5 mm. In this operation, unlike the previous Lee-Goldman operation, low-profile implants are used, made of high-tech alloys, with different sizes and directions of the hook-shaped part of the plate, and variable length of the plate itself (Fig. 3). This operation has gained wide popularity among orthopedists and traumatologists and is actively used in modern practice. However, modern studies show quite a number of unsatisfactory functional results in patients who have undergone such interventions [37].

Endoscopic orthopedics of the shoulder and acromioclavicular joints has become a new concept in approaches to surgical treatment of patients with ACJ rupture [15]. High-tech and minimally invasive techniques have led to the emergence of new reconstructive operations [8,9,10]. For example, proposed by w.Petersen, M.wellmann, S.Rosslenbroich, T.Zantop in the early 2000s, the minimally invasive system of button fixation of the ACJ (MINAR) (Fig. 4) [20,30,47], which in 2010 year, a team of authors under the leadership of A.A. Gritsyuk was supplemented with a two-beam technique, etc. [4].

Conclusion

Summing up the evolution of the development of approaches and methods of treating patients with ACJ injuries, we can conclude that enormous scientific, practical and historical experience has been accumulated in the treatment of this group of patients, however, the issue of choosing treatment tactics still remains ambiguous and debatable, which means relevant and requiring further study.

Bibliography

1. B. Boychev, V. Comforti, K. Chokanov 1961: Fixation of fresh acromioclavicular dislocation with a nail inserted through the acromion and clavicle, according to Spizharny Kuntscher; Wippe technique for reduction of dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint using a tape from the fascia lata. Pat. 3988 RB, A 61 V 17/56. Method for treating rupture of acromioclavicular joint ligaments / A.A. Lapusto, P.I. Bespalchuk. - No. a 19990267; Application 03/23/1999; Publ. 06/30/2001 // Afitsyiny bulletin/ Dzyarzh. Pat. departments of the Republic of Belarus. 2001. No2 (29). P.96.

2. Beard I.V., Danilov M.A. Conservative and surgical methods of treating AC joint injuries. Far Eastern Medical Journal, 2014. No4

3. WHO . Global injury report: preventing the leading cause of death 2014. Identification number: wHO/NMH/NVI/14.1.

4. Gritsyuk A. A. Minimally invasive two-bundle fixation of the acromial end of the clavicle during its dislocation. (2010): 56.

5. Gorinevskaya V.V. Dislocations of the clavicle // Fundamentals of traumatology. M. L.: Medgiz, 1938. P. 513-514

6. Elizarov M.N. X-ray diagnosis of rupture of the coracoclavicular ligament. On Current issues in clinical radiology and radiology. Moscow, 1965. pp. 179-180.

7. same A.n. Apparatus for the treatment of dislocations of the acromial end of the clavicle // Orthopedics, traumatology and prosthetics 1975. P.49-50.

8. Kalinsky E.B., Kavalersky G.M., Kalinsky B.M. et al. Surgical treatment of patients with consequences of dislocation of the acromial end of the clavicle. Journal: Department of Traumatology and Orthopedics. 3(15)2015, p. 17-21.

9. Kalinsky E.B., Kalinsky B.M., Yakimov L.A. et al. Surgical treatment of patients with chronic dislocations of the acromial end of the clavicle. Journal: Moscow Surgical Journal. No4(38) 2014 Pages: 16-20.

10. Kalinsky E.B., Kalinsky B.M. et al. Surgical treatment of patients with persistent dislocations of the acromial end of the clavicle. VI Congress of Moscow Surgeons.

11. Kaplan, A. V. Damage to bones and joints. 3rd ed. M.: Medicine (1979): 184-185.

12. Kozhukeev E.S. Splint for the treatment of dislocations of the acromial end of the clavicle // Healthcare of Kazakhstan. 1964. P. 120.

13. Lee A.D. About a new surgical method for treating dislocation of the acromial end of the clavicle // Orthopedics, trauma.

14. Movshovich, I. A. Operative orthopedics. Movshovich IA. (1983).

15. emergency and specialized surgical care. 10 June 11, 2015. With. 294 – 295.

16. Musalatov Kh.A., Brekhov A.N., Lipovoy B.A. Long-term results of surgical treatment of dislocations of the acromial end of the clavicle with a pin tie. In the book // Proceedings of the Crimean honey. Institute named after Georgievsky.1997, vol. 133, hours 1s 56–59.

17. Pirozhenko V.V. Splint for the treatment of fractures and dislocations of the clavicle // Orthopedist. traumatol. 1955. No. 1. P. 74.

18. Salnikov V.P. Treatment of dislocations of the acromial end of the clavicle with harness bandages // Moscow State University. Publ., 1976. P. 238.

19. Sorokin, A. A. Tactics of surgical treatment of dislocations of the acromial end of the clavicle. // Diss. Cand. Honey. Nauk, M., 2008.

20. Cheremukhin O.I. Submersible splinting of the clavicular joint with metal structures with shape memory // Diss. Cand. Honey. Nauk, M., 2001.

21. Chizhin I.M. Treatment of fractures and dislocations of the clavicle // Surgery. 1939. No. 4. P. 8792

22. Yumashev G.S. 1983, pp. 256–259. Traumatology and orthopedics.M: Medicine,

23. Abbot L, Lucas D. e function of the clavicle. //Ann. Surg. 1954, vol.140, no4, p.583599.

24. Alldredge R h. Surgical treatment of acromioclavicular dislocation.// J. bone jointsurg.1965,47.A, p!278.9.. Allman F. Fracture and ligamentum injuries of the clavicle and its articulation // J.Bone Jt. Surg. 1967. v.49A. No4. p 774–784.

25. Ahstrom JP Jr Surgical repair of complete acromioclavicular separation. // JAMA. 1971 Aug 9; 217(6): 7859.

26. AC joint dislocation: Tossy Classification Tossy et al, CORR, 28: 111119, 1963

27. AC joint injury: Allman classication Allman FL, JBJS (am) 49:774784, 1967

28. AC joint injury: Rockwood classication In: Fractures in adults, edited by Rockwood, CA, 13411414, Lippincott Raven, 1996

29. Allman FL. Fractures and ligamentous injuries of the clavicle and its articulation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1967;49(4):77484. J Bone Joint Surg Am (link) Pubmed citation

30. Bhandari M. EvidenceBased Orthopedics. wileyblackwell. (2012) ISBN:1405184760.

31. Bohler L. Calci ed tendonitis of the shoulder. Radiology. Am. J. Surg., 94 (1957)

32. Bosworth BM Acromioclavicular dislocation: endresults of screw suspension treatment // Ann. Surg. 1948. Vol. 127, No. 1. P. 98–111

33. Brosgol MP Traumatic acromioclavicular sprains and subluxation // Clin. Orthop. 1961. No. 20. P. 98–108.

34. Bucholz Rw, Heckman JD. Rockwood and Green's fractures in adults. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. (2009) ISBN:1605476773.

35. Carrell wB Dislocation of the outer end of clavicle // J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1928. No. 10. P. 314.

36. Davies AM, Hodler J. Imaging of the Shoulder, Techniques And Applications. Springer Verlag. (2006) ISBN:3540262482.

37. Fade GE, Scullion JE Hook plate xation for lateral clavicular malunion // AO Dialogue, 2002. Vol. 15, No. 1. R.14–18.

38. Gerber C. Rockwood C. Subcoracoid dislocation of the lateral end of the clavicule: a report of three cases. //J.bone joint surg.1987, 69 A6, p.924–927.

39. Howard HJ Acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint injuries // Amer. J. Surg. 1939. No. 46. P. 284

40. Judet J. Lex luxations acromioclaviculares recentes // Concours Med. 1978.V.100.N.22.P.36143646.

41. Kennedy JC Complete dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint. Trauma1968, 8, pp. 311–318.

42. Marinček B, Dondelinger RF. Emergency Radiology, Imaging And Intervention. Springer Verlag. (2006) ISBN:354026227x.

43. Larsen E., Bjergnielsen A., Christensen P. Conservative or surgical treatment of acromioclavicular dislocation // e journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1986. Vol. 68A, No. 4. R. 333355.

44. Murry G. Fixation of dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint and rupture of the acromiolavicular ligament. Cand med Ass. J. 1940, 43, p.207–211.

45. Murray EG An appliance for the conservative treatment of acromioclavicular dislocation // J. Bone Jt Surg. 1946. No. 24. P. 164–165.

46. Phemister DB e traetment of dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint by open reduction and threaded wire xation. J.Bone joint surg. 1942, 24, p. 166–168.

47. W. Petersen, M. Wellmann, S. Rosslenbroich, T. Zantop et al. Minimal invasive Akromioklavikulargelenk Rekonstruktion (MINAR). Obere Extremität, September 2009, Volume 4, Issue 3, pp 154–159

48. Rockwood CA, Williams GR, Young DC. Acromioclavicular

incidents. In: Rockwood CA, Green DP, Bucholz Rw, Heckman JD, editors. Fractures in Adults. 4th ed. Vol I. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Raven; 1996. pp. 1341–1413.

49. Schaefer FK, Schaefer PJ, Brossmann J, hilgert RE, hellerM, Jahnke T. Experimental and clinical evaluation of acromioclavicular joint structures with new scan orientations in MRI. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:14881493.

50. Tossy, Mead n., Sigmond h. Acromioclavicular separations: useful and practical classification for treatment // Clin. Orthop. 1963. V.28. N2 I.P. 111 119.186. Tu er: see Cadenat.

51. JD Tosy, hM Sigmond. Acromioclavicular separations: use—full and practical for treatment Ion orthop, 1963.

52.iel M et al. Isolated Acromioclavicular Joint Pathology in the Symptomatic Shoulder. Musculoskeletal J, 1937.

THE HISTORY OF TREATMENT OF AC-JOINT DAMAGES

1E. B. KALINSKIY, 1A. D. CHENSKY, 2B. M. KALINSKIY, 1L. YA. YAKIMOV, 1I. N. ROZOCHKIN

1I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow

2City Clinical Hospital named after SP Botkin Moscow City Department of Health, Moscow

Information about the authors:

Kalinsky E. – MD, PhD, First MSMU IMSechenov, Department of Traumatology, Orthopedics and disaster surgery, Assistant prof.; e-mail: Eugene_ [email protected]

Chensky A. – professor, MD, PhD, First MSMU IMSechenov, Department of Traumatology, Orthopedics and disaster surgery, Professor

Kalinsky B. – MD, SP Botkin's Moscow State Clinical Hospital, Head of Traumatology department

Yakimov A. – professor, MD, PhD, First MSMU IMSechenov, Department of Traumatology, Orthopedics and disaster surgery, Professor

Rozochkin I. – First MSMU IMSechenov, Faculty of Medicine, 5th grade

e research of acromioclavicular joint (AC-joint) trauma began in ancient times. From the time of Hippocrates to the present day we continue the study of this disease and the development of methods to treat it. e frequency of occurrence of the trauma in the modern world reached 26.1%, ranking third a er the dislocation of the shoulder and forearm. In this review, to your attention will be presented the main historical stages of studying the problems of the AC-joint traumatic damage, the evolution of approaches to diagnosis and treatment of patients, as well as prospects for the development of the scienti c and practical direction of this eld of Orthopedics and Traumatology.

Key words: acromioclavicular joint, AC joint, AC joint ruption, surgical treatment, history of treatmen.

Treatment of ruptures of the acromial ligaments of the clavicle

A rupture of the acromioclavicular joint is treated conservatively or surgically ; the method of providing assistance depends on the degree of damage and the condition of the victim. Conservative healing methods include:

- use of painkillers;

- using cold compresses;

- wearing support bandages.

Moderate ruptures may require the application of a bandage to protect the damaged area and limit the movement of the joint.

Surgical treatment involves eliminating severe bone deformities. Surgery may be required to remove the end of the collarbone and repair the ligaments.